“Il est comme un chauffeur de taxi!”

Which means he could be Black, Haitian, Iranian, incomprehensible, immigrant, shifty, or that he does not dress well, speaks in monosyllables and may not be a taxi driver at all. But, a “taxi driver” is at the bottom of the social ladder when it comes to classifications–a wee bit above, perhaps, the folks who walk down the pavement outside your house, hurling your trash into garbage trucks. If I had not heard someone make this comment recently, I would not have had the idea for the title of this reflection… And this is pretty much a good representation of class-based labeling in the society we live in.

Variants? “She grew up in a barn!” In a semi-feudal, pre-industrial society, you would hear the same label with a different spin, “He talks like a servant.” Or, in a caste-ridden society, one would hear, “Look at him, just like a butcher, scavenger or a cobbler.”

Class has been defined, often with academic triteness, according to income level, wealth, living standards and behavior patterns. Class in Montreal and North America is often associated with where you live, how you live, how you were brought up, what schools you went to, whether you have refinements in food habits, in clothes, what cars you drive. But ultimately, it is a question of what’s in your bank account, or what you have inherited, which guarantees that you would not have to work for a living. And in that sense, class points towards the traditional historical convergence of Barons with Robbers and Thieves, of Rogues and Swindlers with Bankers and Industry Captains, all with a penchant for tax-dodging philanthropy.

Why Class is a confused notion in North America?

In North America, there are notions and definitions of class that have been purposefully grafted and redefined, so that the dreaded notion of “class warfare” can be skirted around. After all, the notion of a “land of opportunity” or a “self-made man” pre-supposes that you can be born into a class and can grow out of it. So, if your parents were of an immigrant working class background–perhaps plumbers, gardeners and carpenters– it is quite possible that you will become an Engineer with an MBA and move into a gentrified neighborhood in no time. So, while you grew up eating red meat, pasta and hamburgers, you end up indulging in Nuevo Latino cuisine where the fish comes from private fisheries and the wine is imported directly without SAQ involvement. Class is all about how you conduct yourself.

–But, is it really?

In North America, Class is a broad spectral band of blending and overlapping economic “frequencies. Thinking of this spectrum in our minds, many of us see certain rough stereotypes.

The Working Class

People who do not have a college degree, have a small – or no – net worth, and who engage in physical work while living in rental housing or in heavily mortgaged homes. The working-class have little control over the conditions and kinds of work that they do.

The Lower-middle Class

These are families who have much in common with everyday working people, but they may own a small business in which the whole family is involved. They are not well-off, nor especially educated, but they do have some small measure of security.

You can get all races, cultures in the working class and political beliefs vary. While the majority is white, compared with the composition of the whole population, they are disproportionately people of color and women. A sense of affiliation, both ethnic and religious, is stronger among working-class and lower-middle class groups than it is among the middle-class above them.

Low-Income or Poor:

This group of people suffers from chronic insecurity, lack of work, dependence on welfare, a pattern of frequent disruptions of all the stable supports that shore up “The American Dream.” Again, people of colour and women are unjustly numerous in this group.

And, as the Idle No More movement has reminded citizens, Canada, as a part of its colonial legacy, calmly and ruthlessly consigns a disproportionate number of her First Nations peoples into the low-income category. According to a Study done by the Institute for Policy Alternatives (see http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/reports/docs/Aboriginal%20Income%20Gap.pdf) “Not only has the legacy of colonialism left Aboriginal peoples disproportionately ranked among the poorest of Canadians, this study reveals that the disturbing levels of income inequality continue to persist. In 2006, the median income for Aboriginal peoples was $18,962—30% lower than the $27,097 median income for the rest of Canadians. The difference of $8,135 that existed in 2006, however, was marginally smaller than the difference of $9,045 in 2001 or $9,428 in 1996.”

Then we have the Professional Middle Class:

These are folks who are typically college-educated, salaried and managers and their family members.

Disproportionately white, these people have university degrees, have frequently gone to private schools, are secure in their home ownership, enjoy considerable control over their work, experience more and longer economic security. They go on special trips, frequently to foreign destinations, they eat at restaurants, listen to concerts, and relish “the good life.” Their net worth gives them a cushion, and their pensions often depend on portfolios of equity holdings that can supply income when they cease to work. They have much in common with the class who are the real owners in the economic sphere.

Class of Owners:

This group of people in the United States owns a huge amount of the country’s wealth and its share has been continually increasing in the last 30 years. In his foreword to the well-known study of inequality, The Spirit Level (Bloomsbury Press 2010), former U.S. Secretary of Labor, Robert B. Reich observed: “The latest data shows that by 2007, America’s top 1 percent of earners received 23% of the nation’s total income – almost triple their 8 percent share in 1980.” And Reich adds: “Top investment bankers and traders take home even more than CEOs or most Hollywood stars. For the managers of twenty-six major hedge funds, the average take home pay in 2003 was $36.3 million, a 43 percent increase over their average earnings the year before. The Wall Street meltdown took its toll on some of those hedge funds and their managers, but by the end of 2009 many were back.”

These groups of people live in a world of their own. Their children, of both sexes, go to select prep schools, they vacation in Aspen, Colorado and the Swiss Alps, they control whole business sectors, and their lobbyists deeply influence almost every piece of congressional legislation. They have holdings and homes in the United States and across the globe.

Here incidentally, is a rather interesting and shocking statistical representation of income distribution in the United States. http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=QPKKQnijnsM

In Canada, with a population of some 33 million, there is also increasing income inequality, and the median total income for all Canadian families is now reduced to $69,860 (2010) from $74,000 (in 2007). (Source http://rabble.ca/columnists/2013/03/number-never-just-number-what-middle-class) In other words, that’s right at the middle of all family total income earned in Canada in 2010. Half Canadians earned below it, while others earned above it.

In reality Canada’s middle class is shrinking very rapidly.

3% of Canada’s population can be construed as upper class. They suck in 42% of the net income of the Canadian economy. The rest of the national income statistic is roughly divided into 40-50% of Canadians who belong to the middle classes with a larger percentage trending towards the lower middle class. More than 1/3rd of Canada’s population belongs to the working class–the class that many upper class and middle class refer to as “taxi drivers” in their casual conversations.

Talking about Class

In the theory of Karl Marx– the German philosopher whose works are republished with absolute ferocity these days and whose readership has magnified several fold, especially after the 2008 meltdown, so much so that leading advisers to Clinton, Bush and even Reagan, quietly acknowledge that “he was right after all” (see Wall Street Journal interview of Dr. Nuriel Roubini http://live.wsj.com/video/nouriel-roubini-karl-marx-was-right/68EE8F89-EC24-42F8-9B9D-47B510E473B0.html#!68EE8F89-EC24-42F8-9B9D-47B510E473B0 )—–there has always been a radically different perspective offered on Class.

In Marxist theory, the class who own the means of production, the bourgeoisie, and the much larger proletariat who must sell their own labor power and do not own the means of production, but produce value, are the two main contending classes. So, it is not so much the ownership of property (which is a secondary result) that is all-important, but the fundamental fact of ownership of the means of production. This fundamental state of inequality, between those who sell labor and those who own it, with the consequent lack of power and decision-making ability for the working poor, is then stratified and normalized as social and cultural classes, and forms the basis of cultural ideology.

Class is thus both an objective and as well a subjective relationship. It is objective because each social class has a relationship with the means of production. It is subjective because, based on this relationship, a perceptive notion or class consciousness is built into society. Thus “common social concerns and fears” create the boundaries of class consciousness.

Most of us, who write, perform, compose and feel the need to express our deeply felt intellectual propensities—also belong to a class. It would be simplistic to suggest that we are all middle class. We are by nature cogs in the wheels of the owners of the means of production. We are the managers and administrators, small business owners, traders, the choreographers and streamliners of the basic and fundamental divide between owners and non-owners of the means of production. We are the petite-bourgeoisie. But we have a choice. And cultural ideology provides us with that conscious way to choose whose side we should be on.

Cultural Labels

In the context and time line we inhabit, there has been a continuous evocation of the spirit of the poor and the working class in music and cultural experimentation. “Whose side are you on?” Is the perennial question that is repeated every generation. One tends to invoke the works of Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Billy Bragg and occasionally the erratic constructs of Bob Dylan or Bruce Cockburn in Canada. But there has been a lot more in the pipeline. One remembers the “2-tone” band, the Specials and their exemplary song Ghost Town—down turn ska at its best. There have been various versions available over the years. The band is still kicking around, but the frenetic ska has given over to slowed-down reggae, as the midriffs expand and the faces droop around the jowls.

And there has been the Asian Dub Foundation, whose charged political electronica, rapcore and Dub lyrics (http://www.asiandubfoundation.com/) , along with the Dub poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson, inspired a whole generation of British Asians and Carribeans.

And finally, there is John Lennon.

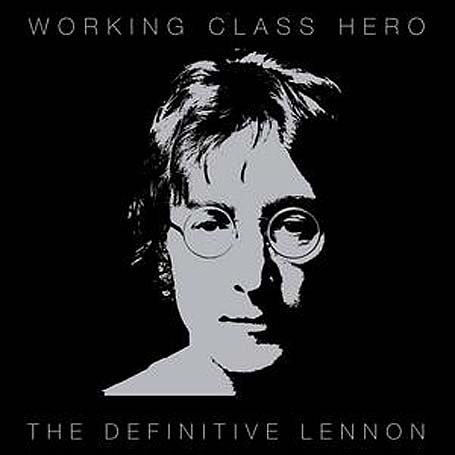

Talking about persistent and transformative cultural heroes, there is someone whose influence, especially towards the end of his career, is remarkable and unmistakable in his choice of whose side he wanted to be on. In 2005, a two disc compilation of music by John Lennon was released.

Called Working Class Hero: the Definitive Lennon contains remixed and re-mastered versions of his songs. It did very well in UK, reaching the top of the charts. It fared poorly in the United States. Take a listen —

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Working_Class_Hero:_The_Definitive_Lennon