“The most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

— Steve Bantu Biko

I remember.

I probably shouldn’t, but I do. It’s a distant memory. Still, like my parents and their parents before them and so on, I remember.

I first crossed the line when I was five years old. I had no idea that’s what I was doing. I didn’t understand the significance of something that seemed so normal, so totally not strange or bizarre. Years later, after I’d already crossed the border several times, I found out just how precious that memory could be.

Every summer, every year, they gather in Niagara Falls, Ontario. They’re Mohawk, Onondaga, Tuscarora, Seneca, Cayuga and Oneida. Collectively, they’re the Six Nations (Iroquois) Confederacy. We prefer Haudenosaunee.

They hail from places near and far. They revive old friendships, make new ones, share big wide grins and belly laughs. Some hold hands to comfort and calm each other as the police gather around them and as they begin to march. Others steady those who walk a little bit slower every year.

They head toward the Rainbow International Bridge, intent on crossing the border into Niagara Falls in New York State. Lots of police control traffic but also watch the marchers closely. The marchers ignore the police as best they can because they’re there for a reason — to teach their children and their children’s children that they still exist as first peoples. They do it to tell governments that we still exist as nations. They want anyone who’d bother to listen to know that after more than 300 years of this, we have not forgotten who we are.

My first crossing, at the age of five, was simple, uneventful. I sat in the back of my parents’ car as we headed north from Syracuse to Kanehsatake. Back then, they called it Oka. The most remarkable part of this trip was looking down from the top of the international bridge from Massena. I’d never been that high before. It made me dizzy, face planted against the window staring at the St. Lawrence River and a ship going down the Seaway.

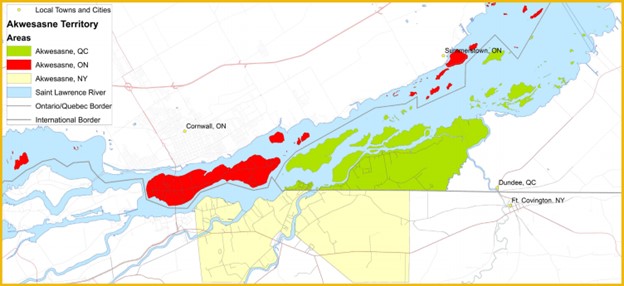

On the other side of that bridge, we went through a small island, Cornwall Island. That’s where my Dad was born, on the Canadian side. But he was baptized Catholic in Hogansburg, N.Y., so he was deemed to be American-born as well. Join the club if you find that confusing.

Moving on, we went over a less exciting bridge from the Island into the small city of Cornwall itself. We stopped at a line of small shacks where a uniformed man inside asked where we were coming from and where we were going. The man barely looked at us. I heard Dad tell him that we were Mohawk and going home. He just waved us through without fuss.

Mom explained some time later that we’d actually gone through the border three times that day. Once when we drove from Syracuse to my aunt’s in St. Regis on the Québec side. I remember we stopped on the way there in front of a small shack beside the road. An old man with a uniform looked out. Dad waved at him. The American customs guy waved back. Just like that we were on our way to Canada.

We crossed the border again when we left my aunt’s place, passing by the same little shack with that same little old man. We crossed the border one last time when we went over the international bridge into Ontario on our way to Cornwall and then to Kanehsatake. We had just been in two countries, two provinces, and one American state in a few hours of one afternoon. The incredible thing was that it all took place within the boundaries of my Dad’s home territory called Akwesasne.

That was too complicated for a five-year-old to understand. However, the explanation stayed with me. I needed to know more about how such a thing could be possible. Even then, it got me thinking about where those lines came from and who put them there in the first place. Who would be dumb enough to split one community into so many parts? I was certain it couldn’t be the Mohawks living there.

One question slid into another. Why, I wondered, didn’t we have our own customs sheds to check people passing through our territories? Wouldn’t it make perfect sense to ask them where they were coming from and where they were going? It seemed not only logical but a darned good idea. I asked my father about this. He shrugged, agreed with me, and said that the Navajo in Arizona did that already. Maybe we Mohawk should, too?

As I got older, my questions became less naive and more politically relevant. By that time, visiting family in St. Regis was lot less informal. They no longer just waved us through once we identified as Mohawk. They wanted to see cards, passes and even passports to make us prove who we were and where we were coming from. No more idle chit-chat about the weather. Everybody and everything seemed a lot more tense and less friendly.

It got much worse after September 11th. All of sudden, Haudenosaunee negotiations to have express ID cards for border crossings slid off the table and into the trash can. National security suddenly became a perfect excuse for governments on both sides of the border to shelve or tear up those treaties of peace and friendship.

We could cite chapter and verse the Treaty of Ghent and Treaty of Utrecht and, my favourite, the Jay Treaty. They stipulated that Indigenous nations had free passage for our peoples and personal possessions across their border because it wasn’t our border.

Presenting these treaties as evidence of our continued existence as original nations, Indigenous Nations, landed like a dead fish with these customs folks. Not so much the Americans as the customs guys on the Canadian side. Like most Canadians, they were the products of poor history classes, and had been taught and then trained by the Canadian government that we no longer existed and neither did our centuries-old border-crossing rights.

This didn’t happen only at Akwesasne or just with Mohawk. Every Indigenous nation situated near the international border felt tensions rise if their citizens wanted to attend meetings, ceremonies or gatherings on the other side of that line. It made everyone affected wonder if governments would simply use “national security” like some magical incantation to make their border crossing rights vanish!

Rather than get angry, I chose to find out more about things like this. Things that most Canadians could not conceive of as possible unless it happened to them. Although, to be fair, anyone who has arrived in Canada from another colonized country might understand how borders can simply be drawn without a bit of concern or thought to the original people who called a place home.

So I prefer to be philosophical about the whole thing in my advancing years. Borders are signposts placed by the latest wave of settlers. They signify shifts in history that tell stories about when and where one wave of newcomers came, stayed or moved along. However, they also tend to erase previous borders along with the story of those who had been there before.

Borders say a lot about who we are as nations. How we guard those borders can be just as informative. They can establish but also erase. Preserve and protect or hem in behind walls of ignorance.

But we remember who we were and who we continue to be.