I had to dive fully in and swim around the poems as in a vast coral sea

Categories

Meditation

If from Every Tongue It Drips (2021) explores distance and proximity, identity and otherness, through the daily interactions between two queer women.

I felt more keenly aware of being a visitor and a guest here on this land — something I had always known instinctively.

Tell me how I can do this and still live.

He walked among the trees. They smelled good. He had rarely taken the time to notice. The smell was a counterpoint to that tendency to see only the claustrophobic solitude of boreal forests. In the winter the forests […]

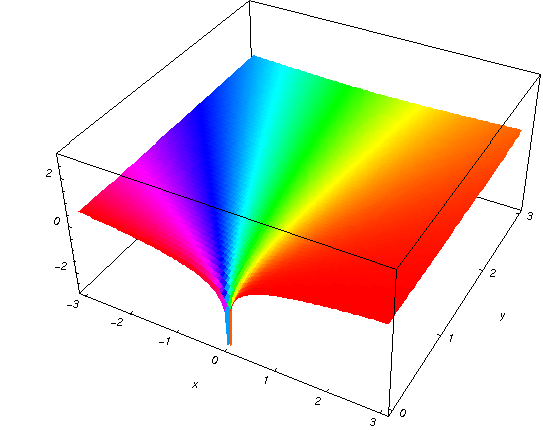

When we say first principles, we claim we are going down to the basics. To a fundamental truth. Being totally iterative, methodical and without prejudice. We are arriving at a fundamental principle. Scientists are not supposed to assume anything […]

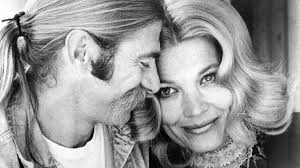

Magnificent. Maddening. John Cassavetes’ Minnie and Moskowitz (1971) is a small story about big love. Seymour Moskowitz, played by Seymour Cassel, is a hapless parking attendant living in Los Angeles. He goes on dates, spends time with strangers at […]

We are the rational and sensible ones with access to almost every piece of information over the Internet. We are intelligent, sentient beings.

Having played Hitler,Nixon and a range of serial killers and social screw-ups, and Picasso, for that matter, the aura surrounding his presence in a frame shot is devilishly complete.

In Latin, precarius is something given to you as a favour by somebody else, or in other words it describes a bond of dependency.

In Che’s imagination, two things were inextricably linked with sustenance – freedom and sacrifice.

There is something obscenely theatrical about the Bhopal disaster. On the night of December 2nd 1984, a leak at a Union Carbide pesticide plant caused a 27-ton cloud of methyl isocyanate to drift across the Indian metropolis of Bhopal, […]

What is it to be indigenous? Indigenous to the land or to your self. Indigenous even to your heart. What is indigenous? Who is indigenous and to what? For we are metaphors of our minds, but the reality is that […]