Introduction

We conducted this conversation using voice notes because that allowed us to think expansively. We prefer this way of working because it allows for thoughts that lie at the edges of understanding to seep through. The film this conversation is referring to, If From Every Tongue It Drips (2021), was composed through a series of voice notes and conversations, so it only seemed fitting to use the voice note as the medium to speak about quantum theory, gender identity and the film. Our voice notes have been lightly edited for publication.

Film description

If from Every Tongue It Drips (2021) explores questions of distance and proximity, identity and otherness, through scenes from the daily interactions between two queer women – a poet and a cameraperson. Created in three locations – Montréal, Batticaloa and the Isle of Skye – and connected through languages – Urdu, Tamil and English – as well as personal and national histories, music and dance, and the gaze of the camera lens, the film delves into subjects both expansively cosmic and intimately close – from quantum superposition to the links between British colonialism and Indian nationalism.

Trailer: If From Every Tongue It Drips

Director/Producer: Sharlene Bamboat

Performer: Ponni Arasu

Camera Operator: Sarala Emmanuel

Sound: Richy Carey

Edit: Muhammed Nour Elkhairy

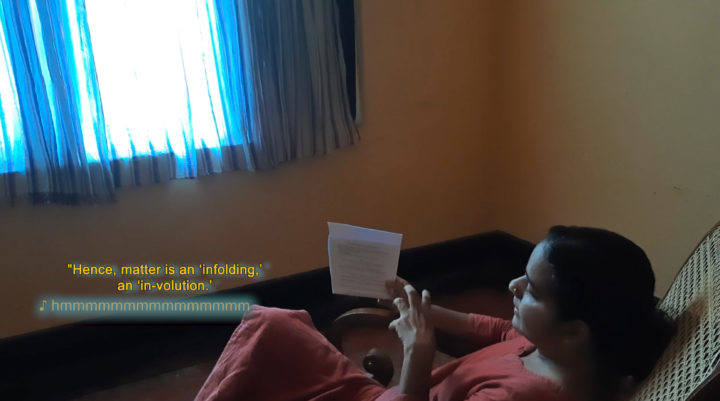

Shar: I thought it would be a good place to start with this image of Sarala, one of the characters in If From Every Tongue It Drips (IFETID), alongside a caption – which is text that she and two other characters are reading of physicist Karen Barad’s work. It was a great starting point (for this conversation) because it led me straight into Barad and the ways in which they speak about quantum entanglement, which my film encompasses. Barad begins their epic book Meeting the Universe Halfway (Duke University Press, 2007) with a quote by poet Alice Fulton from Cascade Experiment (W.W. Norton & Company, 2005), and I wanted to share a line with you from the poem:

Nothing will unfold for us unless we move towards what looks to us like nothing.

This line to me signals a curiosity and openness, which is a really nice way to approach the world, and how I approach my art practice in general. The move towards nothingness, the move toward the mundane; how daily life unfolding can tell us a lot about something. To me, the quotidian structures of time, interweaving with the everydayness of gender and other forms of identity, allow for another kind of opening.

I know it might sound a bit abstract but this is how I connect Barad’s theories, and quantum theories in general, with things that are supposedly fixed – like identities. It also allows me to think about singularities as multiple, and multiples as singular, and, for me, that thought was quite profound when considering it in relation to this film. I think about diffraction and splitting apart, about the fissure of selves as a way to sift through identities and locations, and where and how we can exist simultaneously “herethere.”

Another extension of quantum theory is quantum listening, which is a practice that I have, in very “lite fashion,” been conducting over the last few years, in relation to IFETID. Having completed that film almost two years ago, I am also doing it on a somewhat daily basis, as a meditative practice, as a way of slowing down and just listening; usually in the mornings because I tend to wake up a bit too early these days!

I am guided by musician and composer Pauline Oliveros (Quantum Listening, Ignota Books, 2022), who writes about the simultaneous way sounds affect us and we affect sounds:

Quantum Listening simultaneously creates and changes what is perceived. The perceiver and the perceived co-create through the listening effect.

p. 54, reprint of Quantum Listening, ignota.org, 2022

So, there is a symbiotic relationship between the listener and the listenee; between who is listening and who, or what, is being listened to. And to me, this is very connected to theories of superposition and the ways in which gender is constructed – back to the “herethere.”

Personally, the way I feel about my gender identity is always in relation to others. Whether that be in relation to other people, my geographic location, my surroundings, who I am with, etcetera. This doesn’t mean that I don’t have a fixed sense of self, because I feel I am pretty grounded in who I am. It’s just that while that sense of self (in all its varying identities) is fixed, it is also constantly changing. That tension between the fixed and the changing is something that is truly fascinating to me and something I try to encompass in all of my work.

Fan: Hey, Shar. I tried to find some time in the county so I could send you a voice note with some of the sounds from that locale, but it turned out time there was too tight. I’ve just gotten back to the city and I’m in my insulated apartment, sending this to you.

I wanted to start with what you ended with, which is deep listening and quantum listening. Here’s a quote from page 30 of the Oliveros text:

What is heard is changed by listening and changes the listener. I call this the ‘listening effect’ or how we process what we hear. Two modes of listening are available, focal and global. When both modes are utilized and balanced, there is connection with all that there is. Focal listening garners details from any sound, and global listening brings expansion through the whole field of sound.

So, this is a way to go deeper into this question of this oscillation between the focal, as she calls it, and the global; between the micro and the macro. And I had this experience in Belleville, Ontario when I was out there with my friend Eddy, where we spent half an hour in the yard between the house, which looked like a painting, and the back acreage.

Lamplight fell down and made a perfect square in the grass. And on the other side was the “back 40” as we called it, and the trees were oscillating themselves, writhing in a very still fashion, which reminded me of your invocation of the fixed and the changing. They somehow seemed to be in an impossible glisten between the fixed and the changing. There were these shadows of trees on one side and an archetypally rural Canadian house on the other side of us, and I just sat there and felt time compress itself. I felt the way that my energy extended out into the future with a certain wire of uncertainty, and the way that my energy was expanded into the present as this kind of field of infinity through which I could do this focal and global listening, and ground myself in the details of both the micro and the macro… With no possibility of something like boredom or exhaustion as long as listening was possible, as long as I didn’t block off access to my own listening faculties. And I felt a kind of foundational quality to my past in the form of all the friendships that sustain it, counter to the uncertain strains of the future.

And I wonder what quantum physics has to say about this hypercompression of time into the density of the present. I wonder what quantum listening has to say about that as a practice so that we’re not just listening to sounds, we’re listening to energy and thought as well, which have their own sonic quality. And I wonder how this relates to your film and its afterlife and the fact that we’re talking about a film that you’ve completed now.

What is this film to you at this moment?

How is its completeness rendered by the perpetual incompletion of the present?

I’m gonna try to diffractively connect two ideas. Let’s go back to the first quote from the Barad book you mentioned:

Nothing will unfold for us unless we move towards what looks to us like nothing.

This quote has a poetic cleverness of beginning and ending with the same word, and performs a circularity in its syntax. And it also makes me think about formlessness and how you and I have a resistance to collapsing everything into identity and identification.

This is interesting because the Latin root for identification combines the root word identitas, which means sameness – what we traditionally think of as identity – with facere: to make. I’m coming at it from a Daoist perspective. There’s a subtending nothingness, emptiness or formlessness and all that we are is a making-different of that formlessness from moment to moment. And of course there’s also a thread of continuity that we can pay attention to, that we can name as identity. But we also don’t want to collapse things into identity alone. That just recreates many of the same problems that feminism and queer theory have been trying so hard in the best cases to resist. We can think about identity not as a fixed category, but as a set of details and subtleties and experiences that are not really capturable even by intersectional labels, but are only discernible through experiential deep listening and experiential engagement. And then we can relate that to a more cosmological scale. You used the word “diffraction” and Barad tries to think about diffraction instead of reflection.

“Reflection” smuggles in all the same binaries of self and other, of Hegelian dialectics that seem to inform a lot of the movement of secular thought. Can the metaphor of diffraction be a kind of a new model for thinking relationality? Diffraction would be two drops of water in the cosmic sea. How do their two waves collide and collapse into each other at the moment of their meeting?

We could think of gender this way, relationally, as the touching of two waves. The waves are moving through one another into each other. There’s not a sense that one is the self and one is the other. There’s no need to slap that framework onto it. But rather they move as water in water or wave in wave, overlapping and dissolving into each other. And I wonder if a model for how we conduct the rest of this interview is: how can we work diffractively? How can we work with the material of formlessness – the nothingness that precedes all being, and that subtends all being?

Shar: The afterlife of the film has been interesting for me, unraveling concepts, ideas and relations that extend beyond the film itself. The concepts of “the quantum” continue to unfold in conversations like these, where I dig deeper and deeper into Barad’s ideas and their interpretation of the energies around us… which to me is not separate from the way I’ve come to interact and create new relations with people, like yourself. This conversation is a great example. Of course, talking about quantum theory is a logical discussion to have in relation to the film, but gender identity, less so. It is through the afterlife of the film (or present and past life of the film, if we think about time as not linear) that I am able to unpack other tangents and concepts that IFETID brushes up against, however forcefully or gently.

I resonate with what you say about not needing to “slap the framework of self/other, because we can think about things as water in water and wave in wave.” This is creating a really nice shape that I often use – and make hand gestures with – to describe my work, which is one thing moving, simultaneously opening, closing, without and within. I attempted to do that with If From Every Tongue it Drips, by trying to make all the different aesthetic and sonic strategies, big Histories and small histories, “flow” into and outside of each other. This relates to the ways in which I think about gender, too, as something that is mutable for me. That allowance of change that I give myself is really quite liberating. To not feel like I need to always be the same thing, especially as my body, thought patterns and desire change as time moves.

How do you imagine your mutable self to be, in general and also in relation to gender? Perhaps you can talk about how, if at all, it is reflected for you in the film?

Fan: An aspect of the film that struck me was that it was shot by your friends remotely. This was a partial decision, a partial act of necessity in the midst of the pandemic. Relation always requires some degree of surrender as waves travel into and through each other, but here the stakes are plainly aesthetic: you gave your film over to the lens of your loved ones, and let that resonate with you from across continents. I found this to be a courageous decision, and it made for a film that was so vastly different from Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (2019), a previous film of yours that I loved, which was also the fruit of a collaboration – one with perhaps more proximity to the back-and-forth, more control in the nature of the images. But I’d love to hear more from you about the differences between these films and their respective processes of creation.

Shar: IFETID was an exercise in giving up control as an artist. I sent the two characters in the film, Sarala and Ponni, very loose directions of what I wanted them to film – sometimes it was a shot, a sound, a particular visual, a feeling – and then they would send me back whatever they interpreted from that. Sometimes it was exactly what I had envisioned; oftentimes it was not, and I just went with it. I leaned into that space of giving up control, and that to me is part of the process of working with others, especially working with others who aren’t filmmakers, and even more so because I have never been to Batticaloa, the place they live and where the visuals of the film were gathered.

I allowed them to lead me through their lives, landscape and location in a way that felt welcoming and curious, and also opened up to the possibilities of all the things I do not know. I don’t know if this is courageous, or just practical, or honest, because of the conditions under which the film was made – long distance, during lockdown. This is something I try to lean into in most of my work, which is to accentuate the things I do not know just as much as I am trying to tell you something I do know. In some way, just as my work straddles the inbetweenness of identities, location, experiences, it does the same with knowing and not-knowing.

The film Bugs & Beasts Before the Law was made in collaboration with Alexis Mitchell, with Richy Carey doing all the sound design and composition. For this project, the process of collaboration was very different. Alexis and I have been collaborating as a duo for 14 years, and therefore we work together from beginning to end and are enmeshed in the entire process of the filmmaking. Whereas with Ponni and Sarala, I had asked them to join the film that I was already thinking about and had already conceived. This is not to say that they didn’t influence the film or contribute to it in deep ways; it was just a different process than the way Alexis and I work.

Another link between both films is my friend and sound designer Richy Carey, whom I have now worked with on four projects. We often begin by talking and writing to each other – not just about work, but about our lives and the things going on in them. For IFETID we wrote each other letters every two weeks for about seven months before the film was made, so that when we were actually creating the sound, we had a mutual understanding and trust for how things were going to be created and what each of us wanted. This to me is the exciting part about collaboration, which often is with my friends and people that I build trust with.

Fan: The scene that was most indelible to me from IFETID is the one with the doubled reading of the quantum physics text. (See the image following the trailer.) The combo of your two voices roughly overlapping, the music gently snaking through the background, the quasi-3D text on the screen – it put me into this fugue state that the rest of the film before had been preparing me for, and that the film afterward felt like a comedown from. I delight in a mind-bending aphorism, which was what those physics quotes felt like, and in those moments when cinema strains to perform the language that’s on screen.

Here’s an aphorism I’ll throw out there: The fugue state is the experience of pure potentiality, the preparatory grounds for the Mutable to flow out. I’ve recently been seeking ways to have primordial, prelinguistic experiences that tap into the ancientness of the void. The void is the suspension of actuality: it is the universe of the uncertainty of things that have not-yet-become, and so are plump with the potential to-become-anything. I could never deny how powerful the symbolic charge of gender and other intersectional identities are; the symbolic realm is where we navigate real relationality, after all; where we slowly disambiguate our projection from another’s reality, and thus where real violence and real recognition happen. But I want to find spaces for experience that draw us closer to a presymbolic Real, which I thought you did beautifully in the superimposition scene I mentioned above; you were using symbolic materials (language, concepts) to diffract and destruct their own symbolic nature, by making the whole of it all feel so fuguelike.

Shar: Thank you for saying that. I love this feeling you’ve outlined of “fuguelike” – and the potential of anything and nothing being possible. It’s such a liberating feeling that it becomes overwhelming, and that’s often what I feel or experience when I read or think about quantum theories. It feels so unbelievably vast and full of potential. I feel this way about gender as well – the expansiveness of allowing yourself to feel it entirely on such a vast spectrum as it has the potential of being is exhilarating. Maybe that is the feeling you, and Barad and Sarala in the film, are describing as the void: The void is not absence. Indeed, Nothingness is an infinite plenitude. Not a thing but a dynamic opening that cannot be disentangled from what matters.

Sharlene Bamboat: Sharlenebamboat.com

Fan Wu: linktr.ee.com/fanwu4u