Introduction

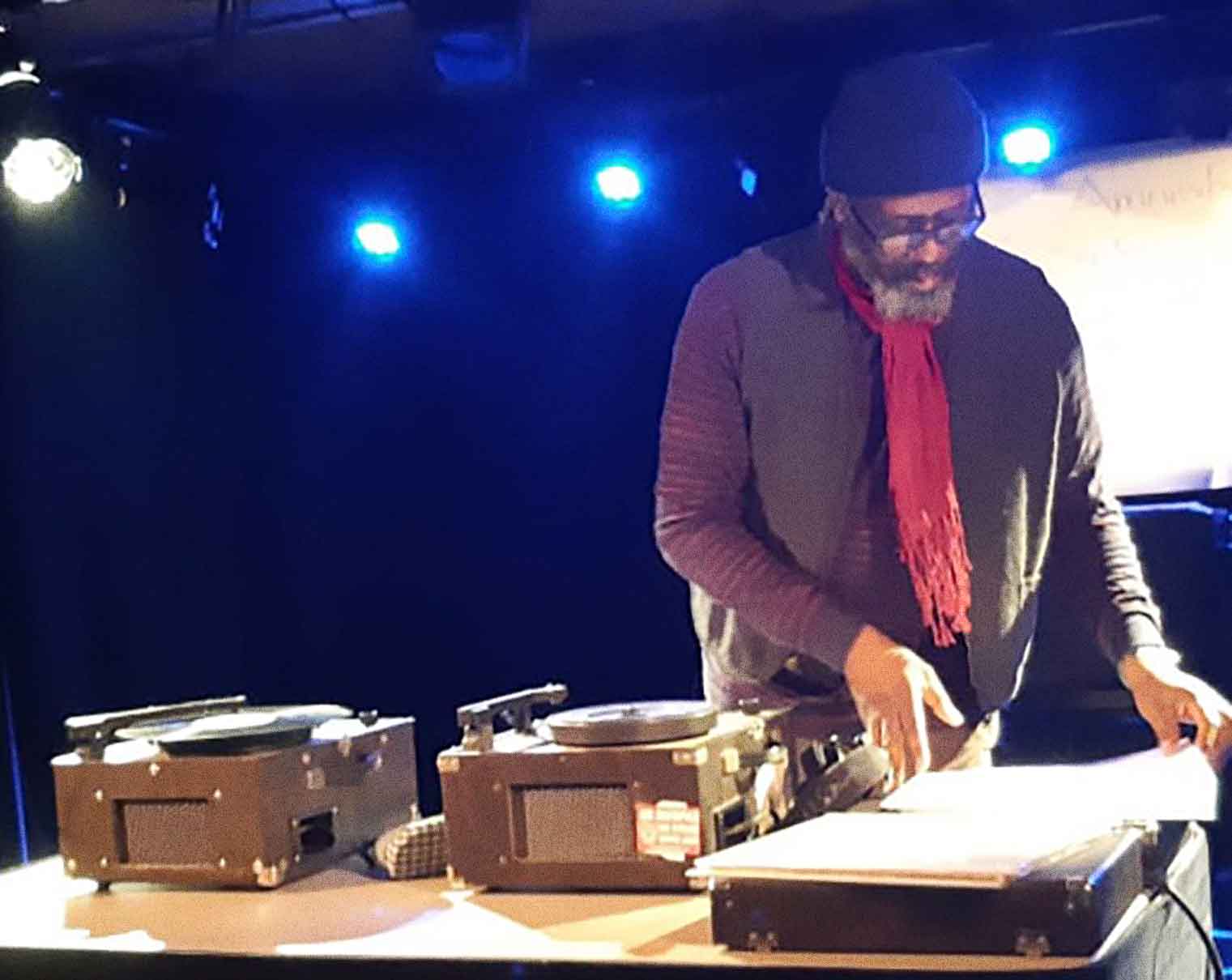

Studies in jazz have evolved over the last century, from celebratory journalistic riffing on productions by African Diaspora musicians and their acolytes to rigorous philosophical inquiry and theorizing on the links between the art of jazz and social history and aesthetic theory. Themes include race, ideological constructs, performance practice, and the role of improvisation. In Montréal, Andy Williams, an accomplished creative deejay who has brought his fresh thematic mixes drawn from an enormous personal collection to venues across Europe, Canada, South Africa and the United States, brings a seasoned perspective to the discussion.

With more than 40 years in the music business, Williams wears many hats: he is a music historian, event curator and lecturer, and has been an educational coordinator. Among his many deejaying projects, he collaborates with Lewis Braden—aka DJ Sweet Daddy Luv—in Jazz Amnesty Sound System, and he has taught several courses on Jazz and other African Diaspora musical genres from the perspective of a post-modern practitioner of the art form.

In the field of education, there is a great interest in using jazz as a metaphor in order to think beyond the individual or organization.

While “fugitivity” is a significant idea that is echoed across the field of jazz studies, given the dialectic of carceration/escape that is built into the concept of slavery and its aftermath, Williams as an educator focuses on “connectivism,” using what he calls “the jazz metaphor” as a cornerstone for his work.

Williams has explored this approach with like-minded colleagues at Goddard College, Concordia University and in other academic contexts, and formulated it in a thesis completed in 2018. He is currently applying these ideas to courses on the history of jazz that he is offering whenever and wherever he can, either in person or online. Combining music mixes, discussion and conversation with his students, Williams’ work places him in the category of the storyteller—but his pedagogical approach also involves sharing, and that means listening to what others have to say.

What follows is a slightly streamlined transcript of my conversation with Andy Williams. Excerpts from his 2018 thesis, “Jazz and learning cities: Motivating and enhancing learning among disenfranchised youth,” have been added in italics to provide greater detail and context.

Your thesis centres on using the jazz metaphor in an education context and developing connectivism. What got you interested in this approach?

In the field of education, there is a great interest in using jazz as a metaphor in order to think beyond the individual or organization in which the individual inhabits. The anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson (1990) used the concept of jazz metaphor to describe the way to “compose a life: For many years I have been interested in the arts of improvisation, which involve recombining partly familiar materials in new ways, often in ways especially sensitive to context, interaction, and response.”

I was talking to a lot of professors in the States and Canada, and some friends of mine—Eric Lewis at McGill, Kahil El’Zabar from Chicago and Medusa from California Arts School—yeah, we were all brainstorming and feeling out if this can be legit or adequate, if this could be a course or a subject… and I took notes and wrote it down. We spoke about it at great length and […] it became my thesis.

Jazz exemplifies artistic activity that is at once individual and communal, performance that is both repetitive and innovative, each participant sometimes providing background support and sometimes flying free. […] Alfonso Montuori (1996) refers to his experience as a professional musician and record producer. He believes that classical education and jazz have much in common: creativity, learning, collaboration, improvisation and organization. […] As a proposed classroom model, within this metaphorical context, jazz would look like a jam session and the teacher more like a band leader.

There’s the idea of using the jazz metaphor where people participate rather than having knowledge just thrown at them. It’s more of a participatory approach.

Related reads

A. Yeah, exactly.

Peter Drucker (1992) presents an image of the workforce of the future made of self-employed knowledge workers with a ‘portfolio of different interests and capacities’. In such a vision of the economy, the metaphors for education based on regimented factory or the hierarchical arrangements of industry and strict military discipline will not be effective (Montuori, 1996). For the classrooms of the digital future, jazz provides a much needed example of collaborative, social creativity (Montuori and Perser, 1996). […] The future is connected and collaborative and therefore once again the jazz metaphor is more congruent with the way classrooms, curricula and teachers should re-invent themselves for the realities of the digital age.

Connectivism is an important term in your thesis. Can you give us your definition of it?

This is a term referring to how learning occurs in networks, which coincides with my discussion of how jazz intersects with the interconnected learning tools of the digital age, particularly among youth. […] Connectivism is a term that proposes that learning and knowledge exist as embedded within networks. For Siemens (2005), a researcher who studies this concept, “connectivism presents learning as a connection/network-forming process.” He maintains that knowing where to locate information is more important than knowing information. For Siemens, learning rests in diversity of opinions and viewpoints within the connections of a given network (2004).

It’s a global idea that brings jazz enthusiasts together. Most of our meetings, whether at McGill, CalArts [California Institute of the Arts] or Chicago, were all about that. It was all about bringing people together.

Different types of groups and different types of institutions involving jazz [are examples of how it works]. CASS Tech High School in Detroit has a really well-known jazz program. There are all kinds of different programs, from Jazz Mobile in New York, to Juilliard… wow, the list is pretty lengthy.

As a jazz enthusiast and listener, I have come to understand the importance of my Black musical heritage and why it appeals to me due to the abundance of stories which are important historical facts of the Black Experience in the Americas. Many of the stories date back to the Atlantic slave trade and the arrival to the Americas of my ancestors and the way these narratives can be incorporated in a school environment or curricula […].

Over the years I’ve been inspiring students with an eight-week program for three semesters of various subject matters related to jazz. The focus of Black classical music history can be transferable in various attributions on how jazz music can be found in much of our literature sightings, sociologically. Liner notes from a record (a recorded disc) represent an interesting source where the record can be envisioned as a picture book giving the students a biography and the repertoire of a musician. During the musical discovery of notes and time signatures, students can discuss the music structure and its characteristics where they can be taught how words and phrases are used. Students studying jazz become […] able to connect in various ways by pictorials, writing styles of Black oral traditions and the music itself.

So with jazz, it’s not just the music, it’s the cultural context and the history.

[Yeah,] I’m surprised it’s not seen as a course. That’s why I started to write about it and talk about it. I think you’re one of the first people I spoke to about it, back in the day. I’ve done two years of using jazz as an educational tool already, and the courses were well received. I also used it in the PACE program at McGill [Personal and Cultural Enrichment Program], and that was well received.

The complexities of jazz music, for scholars improvising in a congregation, show a clear and powerful example of how individuals and collectives can coordinate, innovate and be productive during this digital age. Jazz is a great example of the way a medium can draw attention and create inclusivity in an educational scheme, which allows one to be free while living within the structure of sound.

The course outline I have here is from 2016, so you’ve been doing this for a while already.

Oh yeah!

In your thesis you mention hip hop as an extension of jazz. What are the similarities that you see between hip hop and jazz?

Well, call and response is one, improvisation is another.

The addition of jazz into a secondary school curriculum is made easier by modern students’ affinity for contemporary hip-hop, which samples jazz. As author Jeff Chang points out “In the real world, cultures layered, blended, and sounded together like poly-rhythms of a jazz song… In its truest sense, this kind of integration could lift everyone” (Chang, 2005). Now the music has come full circle where the audience can respond like the old days of rhythm and blues (“call and respond” hollers such as “Hide-de-hide-de hide-de-ho”), which is now a similar pattern to hip-hop call-outs dating back to the spirituals of the church.

And of course, there are the links to African tradition that are similar.

Absolutely.

With the emergence of hip-hop culture in the late seventies sampling jazz riffs and reinventions of African musical rhythms (hybridization) in the post-slave era, we now see the magnitude and the diversity of jazz globally. Robin D. G. Kelley coined the term “polyculturalism” to try to revive an innovative and radical vision of integration of jazz. Polyculturalism is built on the idea that civil society did not need Eurocentrism at its core to function... It is accurate to understand jazz as a fusion of European harmonic structures and practices with distinctively African elements such as syncopation, swing, and complex polyrhythms.

One thing I found interesting in your thesis was how in the early history of jazz, right after the American Civil War, there were all these band instruments available, and availability of these instruments was one of the reasons jazz developed the way it did with saxophones and trumpets.

Many jazz historians say the American Civil War significantly shaped the path of Black American music, as the military discarded many old band instruments. These instruments found their way into the hands of Black musicians, who strove to produce music, often using unorthodox techniques for clarinets, trombones, and other instruments.

That actually started from the Sousa bands in New Orleans. I mention that a fair bit and there were a whole lot of scenes I made use of.

From 1890 onwards Black brass bands were abundant in New Orleans playing parades, functions and funerals. A New Orleans funeral would have a large squad of musicians singing songs such as “Just a Closer Walk with Thee”, “Flee As A Bird” and other dirges. Returning from the cemetery the band would launch into a swinging beat with “When the Saints go Marching In”.

I saw a link to hip hop, because in some documentaries on hip hop, you get the sense that young people weren’t getting access to these other instruments but they used turntables because that’s what they had available. They made use of whatever materials were available to make the music.

That’s correct. Lew [Lewis Braden, from Jazz Amnesty Sound System] and I had the idea that we should start using turntables as an instrument. […] In Continuing Education at McGill, I brought my turntables to the classroom every day.

I gather from your thesis that the role of the teacher in this kind of pedagogy is really different. You’re just sort of helping people to make connections amongst themselves.

Yes, and those classes are pretty big… 40 people. [The need for this approach] was shown to McGill and CEGEPs [Québec community colleges], but it was disregarded.

Really?

I can’t get a job teaching that [course]. The only time I got a job teaching that was when I was at McGill in Continuing Ed… And McGill got rid of the PACE Program.

You mention in your thesis how jazz is a blend of several cultural traditions, not only African… there’s also the European influence. How does that work when you’re teaching the course? Do you talk a lot about the European traditions? I mean the African traditions are obviously at the centre of it, but…

Well, there are two different sides, the European style that’s dealing with different types of scales, from pentatonic scales to multiple scales, so that was easily and definitely mentioned.

The new trend of musical compositions seen as poly-rhythmical pentatonic scales practices are now transcribed in various prestigious music programs such as Columbia University, Juilliard School of Music, Eastman School of Music, Boston Conservatory, McGill University, Royal Conservatory of Music/Toronto and Oberlin to name a few. The construction of European music pertains to diatonic scales which are often seen as restrictive and constructed for a selective group. Others not included in this group that undermines the history of varied musical dialogues, the experience was one of years of class struggle and segregation trying to head towards inclusivity. The collective of immigrants that met at Congo Square should be applauded for their work of creating a community with the African drums, German brass, Scottish Highland instruments along with other European modalities.

So the African tradition is like the rhythmic language, the call and response, improvisation…

And different types of instruments, also, like koras can be used as guitars, different types of horns, different types of drums…

And all kinds of microtonal inflections…

Absolutely.

You mention using Ableton music software and you say it works well in a pedagogical context. What does it look like when you use that software? How do you work with it?

[In] small segments and then you build up on it. We start off showing the students how to use Ableton, then we give them small samples and it builds up to having a full paper, a completion of it. Mostly from storytelling to something huge.

Would students be playing an instrument or singing?

Playing an instrument.

Would the students be mostly music students? Or students taking it as an option?

A mixture of both. That’s what makes people more interested in it, because we start giving them an example of how the blues can be brought into the picture and how the blues explosion in the ‘60s became part of the rock and roll scene. We got people more interested in that kind of jargon.

So you use the music and the elements of the music to also talk about social history and cultural traditions and such.

That’s right. And they wanted me to give an example or mention what it was all about. Jazz can be used as “social studies”—that’s what I call it—because the history of it is very deep in terms of bringing all those things to the forefront.

Wynton Marsalis talks a lot about the democratic aspect of jazz, where’s there’s not one person calling the shots, it’s a shared project.

Exactly. I agree with that.

Can you give me an example of an activity you’d be doing in the classroom? Maybe from one of the last ones you did… an example of a lesson plan or an activity that you thought worked.

Well, student deejays like Kid Koala, Mr. Scruff. I used those guys as good examples because they’re bringing to the forefront the music from electro and different types of mediums, and that created an atmosphere where it was just all about improvisation in the music. It didn’t necessarily have to do with jazz music, but just improvisation. It could be students with sticks, and the sticks become a musical sound—and that’s one good way of producing the music.

And do you get younger students who are conversant with newer developments in the music and you’re learning something from them? Does that happen?

That goes through the history. Kid Koala is from Vancouver and Mr. Scruff is from England. Both of those people were in my classes. I’ve had many, many students from different walks of life in my classroom, from musicians to historians.

I noticed in your course outline for the Black oral tradition with hip hop, for example, you talk about the post-civil-rights era.

[Yeah.] Poetry becomes part of that too, right, as you probably know. You stay within poetic feelings and poets can be used as a part of that. A useful tool.

You also have in that course outline a class on Tipper Gore and the censoring of hip hop. […] How would you approach that topic?

We would talk about the political part of that and how it became a sense of branding when that shouldn’t be branded. It should be exposed.

And hip hop did cause quite a bit of controversy because of the content of the lyrics being quite explicit or X-rated at times. People like bell hooks kind of had a complaint about gangsta rap. Wynton Marsalis also had kind of negative things to say about hip hop, saying that it was NOT part of the jazz tradition. And bell hooks mentions that it’s in a way serving as a mouthpiece for misogynistic white America. What do you make of these kinds of comments?

They all should be repeated and it all should be acknowledged. And that’s what bell hooks would say. That’s something she mentioned throughout her courses. It’s something that should always be mentioned because it has a point, it has a background… It’s part of the whole system.

And that’s part of the connectivity thing, too, I guess, because it’s about different points of view. I guess you could say that about jazz itself, as well. I’m thinking of when free jazz was the new thing and was popular among some people, but other people hated it.

That was really not mentioned in Ken Burns’ films. It wasn’t really mentioned and it should have been.

You use the term “accessible tools” as part of the teaching process. What do you mean by that? What are some examples?

Well, you can look at that as any kind of style, whether it’s John Cage or Elton John and folks like that.

So “accessible tools” would be available documents?

Yeah, and sound and noise….

Like through YouTube or Spotify or Bandcamp? Any of the tools we commonly use, you bring them into the classroom?

Exactly.

At the end of your thesis, you bring up the Frankfurt School’s critique of Popular Culture. They’re very critical of popular culture because they see it as creating false needs. You mention that capitalist culture creates false needs for commodities, and the true needs, if I remember well, are political and social agency. Do you find that your approach creates that kind of political and social agency for the students?

Sure! And something that is peaceful and ambient. A lot of background studies that bring in certain things like work or sounds, and sleep and meditation, and different methods of preparing for that.

Maybe one last question. When you’re picking pieces of music to bring in, what are your criteria? What are you looking for?

Different sounds, whether it’s spiritual or it’s gospel, whether it’s funk-related, African-related, highland music, whether it’s funeral music… There are so many different types of places I can go with that.

Andy Williams’ website, Biafrablue, invites you to wade in deep. For his tribute to the musical heritage of Montréal’s Little Burgundy, see this CBC report.