Tiziano Cruz introduces himself as someone from the village of San Francisco, in the northern Argentinian province of Jujuy, where the health system murdered his sister. He comes, in his own words, from a country that yearns to be portrayed as solely white, a country that, if given the choice, would erase its Indigenous past.

As this exuberant procession drew to a close at the theatre “Le National” with crowds milling about, Tiziano, wearing the bare minimum—white underpants, sneakers and a colourful version of the quipus around his shoulders—entered the foyer and waited there alone to receive each incoming member of the audience with a warm hug, for the second part of the performance.

Montréal Serai wanted to know more about Tiziano and his work (and still does). The following exchange took place via Zoom in June 2023, as ongoing protests of Indigenous communities in Jujuy were being met with violent repression, which has continued unabated. Jujuy’s provincial government led by Gerardo Morales has been pushing a reform that criminalizes demonstrations and curtails freedom of speech in a context where the State has been advocating for the mining of lithium and other riches, with the ensuing devastation of the land and the population’s health.

MS: How did you come up with this unique form of expression—organizing a procession involving local Indigenous and Andean communities, combined with a solo performance inside a theatre?

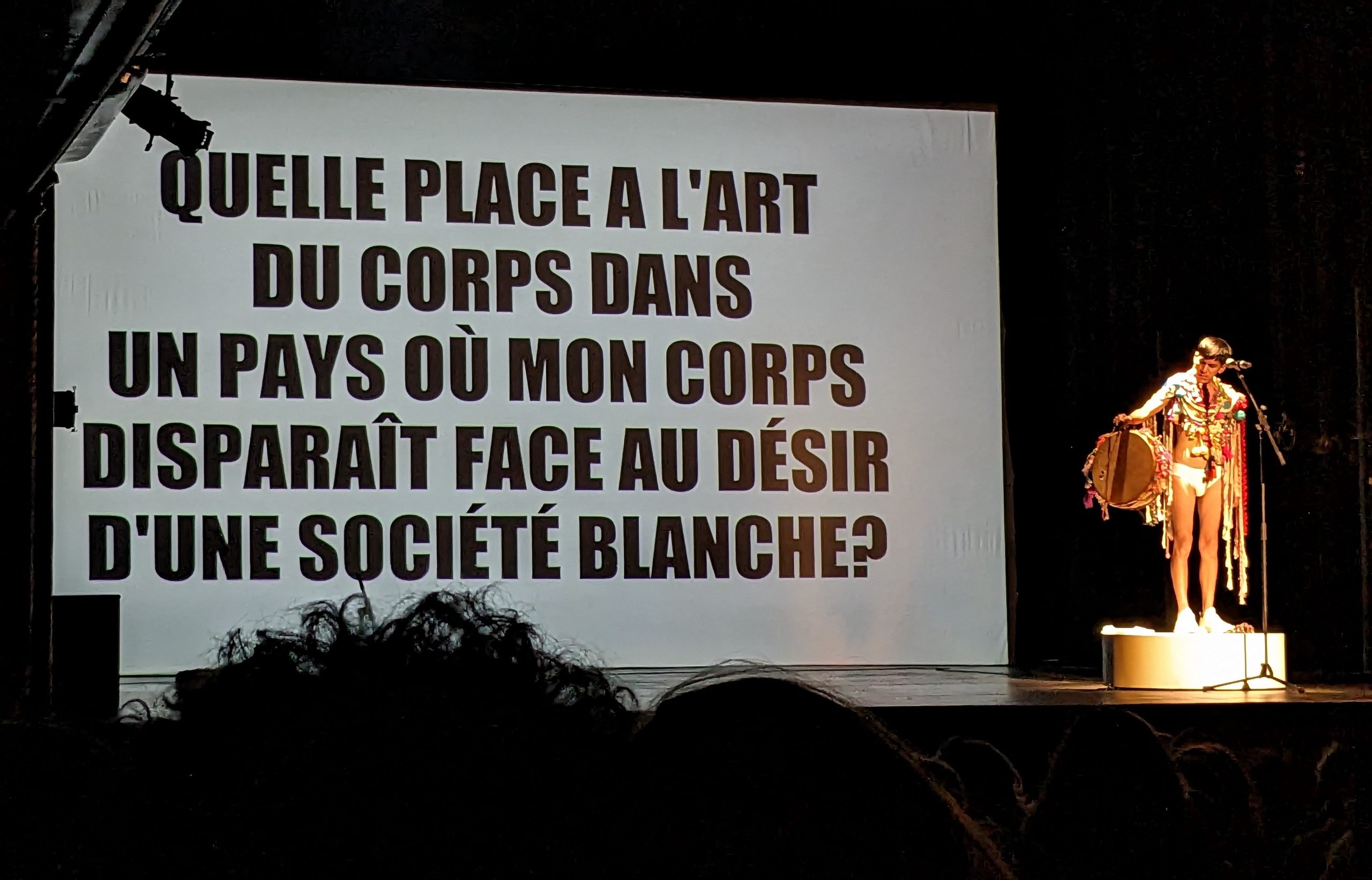

TC: Soliloquio is the second part of a trilogy that questions the role of the art of the body in a country where bodies like mine disappear. The original staging of Soliloquio was the first time an Indigenous person from northern Argentina directed a show in the Festival Internacional de Buenos Aires (FIBA). All performing artists in Argentina dream about making it on Avenida Corrientes in the theatre district (Buenos Aires’ equivalent of Broadway). But when Indigenous artists arrive from the countryside, they realize that this place doesn’t belong to them…

So, in a way, that first version of the procession was a 7.6-km-long way to say goodbye to that “American” dream of belonging, (and) an expression of the need to occupy other places. Not big marquees, but rather the corporeal presence of the Andean culture in spaces that have not belonged to us, as we have been relegated as cheap labour. With the processions, we occupy these spaces as artists.

They are also a nod to the Inca trail—a broad metaphor for that trail as we collect information from other groups. Every time I stage Soliloquio, I prioritize this aspect, and some festivals refuse to include the piece, as organizing the procession requires a lot of work in addition to the show. Moreover, I am very adamant about the fact that every performer needs to be paid; that’s crucial in relaying the message that their culture is valuable. In the case of the Festival TransAmériques in Montréal, Martine [Dennewald] and Jessie [Mill], the artistic codirectors, not only did some legwork to find me, they were also willing to make room for the community aspects of the show.

We were able to bring together five Peruvian communities that have been in Montréal for 10, 20 or 30 years—people of all ages, some of whom were born in Canada. Many parents said they didn’t know how to help their children understand the dimension of their culture or how to leave the shame behind, and the performance opened up those conversations. Being able to spark that awareness, acting as a chacana or cosmic bridge is one of the most valuable and humbling things—it is what keeps me grounded.

MS: You describe yourself as being stripped of or orphaned from your culture. Can you tell us more about the context in which [intergenerational] cultural transmission was interrupted?

TC: My grandparents spoke Aymara and Quechua, but my mother was no longer able to speak those languages. That was a key moment when the tradition was cut off. Then from my parents to me, other traditions were lost. As mining exploration forced communities to leave their homeland and migrate to the capitals, they had to learn how to live in the places they came to with the intention of integrating.

I have had to take workshops in the Indigenous communities to (re)learn my own culture. The coplas I learned indirectly. Only grownups are allowed to sing around the fire, but as kids we listened from afar. So now that I am a grownup myself, I dare to search my memories for those songs that they sang as they came back from harvesting corn. Even more so than history, it is memory that matters in the community, and it is our task to decipher what has been encapsulated in memory and give it meaning. That’s also what we do when we come and meet other communities.

MS: Can you talk to us about your experience in Canada? Could you share what it was like to be in touch with people from the First Nations here?

TC: It is rewarding to learn what some First Nations groups have achieved in terms of asserting the value of who they are. But this is a collective struggle. Let’s not forget that this was once the same territory in a way [for Indigenous peoples of the Americas], before the conquest. There is not much use in protecting a particular community when [a country like] Canada is leading the way in extractivist practices in the South. We need to be wary, and probe what lies behind the progressive façade of issues that are now in fashion [e.g., inclusion, diversity, Indigenous rights].

Which Indigenous lives matter?

—All do.

MS: You are currently working in the Centro Cultural Recoleta. From your perspective, what can be achieved by working within the government?

TC: One of the premises is, we work and militate from wherever we can and in whatever way we can. The superstructure is much bigger than we are, and large-scale revolution eludes us.

I am responsible for curating and preparing content in a historically very conservative and elitist part of Buenos Aires. My aim is to generate openness to artists and communities of the periphery. It takes hours of negotiations – it is the work of an ant – but I believe in the importance of occupying such spaces. I now serve as a reference, and although there are times when I’m exhausted and I want to drop everything, I know that my example is motivating to others. “If he can do it, why can’t I occupy a position of power?” So I go on.

MS: Does gender, your sexual preference, play a role in what you do?

TC: Not exactly. It is implicit in who I am, of course, but in the lower classes, there is no time to reflect about sexuality. If you don’t know what you’re going to eat or where you’re going to sleep, you can’t be reflecting on such stuff. Thinking about sexuality is a matter of class, of privilege.

In my culture, homosexuals were considered wise people, two genders in one… they were community priests… and today we are stigmatized. Imagine—being poor, homosexual and Indigenous!—three damning features in the face of whiteness.

MS: We learned that at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, you worked in a hotel receiving people who were being repatriated to Argentina. What was that like?

TC: It is one of the best things that has happened to me. In 2019 I had been recognized as the best young performing artist of La Bienal in Buenos Aires, so I was the new it in a rising pool of young artists. I felt like I was losing myself, like I had been diverted from my path… and then the pandemic arrived. Within a week I was working in the hotels for returnees who were possibly infected. I brought them food, talked to them and felt that I was really doing something for the world, something as basic as bringing food or talking, connecting with the human part of people. I recovered the feeling of being a useful person who could transform people’s lives. From April to October, walled in within those corridors leading to doors where the possibility of death awaited, I wrote 58 letters to my mother, the foundation for Soliloquio. That opportunity was a lifeline… a cable that brought me back to earth.

MS: Have you performed Soliloquio in Jujuy?

TC: It is easier to travel to Canada than to Jujuy. For me it would be beautiful to perform at home. What triggered the trilogy occurred there: the death of my sister. It is the place where the need to go out and scream was born.

More on the artist

Tiziano Cruz is interested in site-specific experimentation, investigating the possibility of creating new ways of organizing the everyday social sphere and forming shared perspectives.

His academic and informal training paved the way for him to work with public and private institutions and develop a diverse range of skills and knowledge in the visual and performing arts as well as in business administration and cultural management.

Tiziano is the co-founder of ULMUS, a cultural management platform dedicated to mediation between different cultural organizations in Argentina and neighbouring countries.

He currently serves as head content producer at the Centro Cultural Recoleta in Buenos Aires, which is affiliated with the municipal government (Buenos Aires Ministry of Culture).

The third part of his trilogy, “WAYQEYCUNA, Three ways of singing to a mountain,” will premiere in 2024. Dedicated to his siblings, it completes the trilogy starting with “ADIÓS MATEPAC (An essay on remembrance or farewell)” and “SOLILOQUIO (I woke up and hit my head against the wall).”

To follow Tiziano Cruz’s work, please visit the Rosa Studio website and his portfolio.