My grandmother died in 1969 at the age (I think) of 89. My brother and I weren’t expected to go to the funeral and neither of us now can remember exactly when it was. My grandmother had become a burden to my parents and they wanted to forget. After she died, my parents hired an estate clearance firm to empty out the house and all traces of her disappeared.

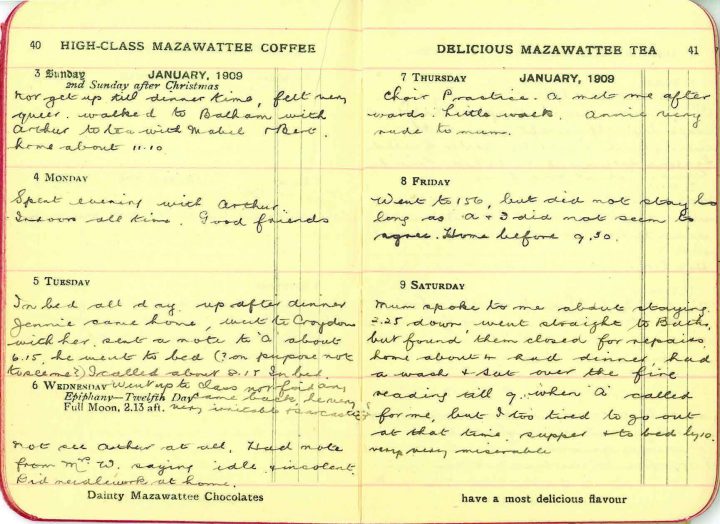

She left a diary for the year of her marriage and the year of my father’s birth, 1909. It’s a small, red pocket diary about four inches by two-and-three-quarter inches, a free gift with the purchase of Mazawattee tea. This my parents kept, and I took it from their house when they died, in 1987. It’s a careful document. The writing is small, neat, even, and for almost the first six months my grandmother did not miss a single day. In early June gaps start to appear, and in July a full week is missed. Then the entries are untidy, spilling over the space allotted for that day. In August the writing is once more firm and clear, and the entries are detailed. The diary ends eight days before my father’s birth, on August 15. My grandmother married in early May, and my father was born three-and-a-half months later, on August 23, 1909.

It’s a relic of empire. The first ten or so pages list the names of every Sunday in the Anglican calendar (with Sundays in bold print), the dates of Oxford and Cambridge university terms, the beginning and end of the law court sessions in London, the birthdays of several European monarchs, the anniversaries of battles, dates of the birth and death of famous men (Charles Dickens, Daniel Defoe, Samuel Johnson, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Franz Joseph Haydn, Richard Wagner…). Pages towards the end show postal rates, tax rates and the average amount of time taken to deliver a letter from London to forty cities across the world; a final table lists the times of the tides in major English, Scottish and Irish towns, given as the difference between high tide in that town and at London Bridge.

When I knew my grandmother, she lived in a run-down terrace house on a forgotten street in West Croydon, the poorest part of town. (Croydon is about ten miles south of Central London, in my grandmother’s time a separate town, now part of Greater London.) Her house had no electricity and no fixed bath. It had an outside toilet and was heated and lit on the downstairs only by gas. Sometime in the early sixties, my father told me she had lived there since 1915 and paid a rent of fifteen shillings a week.

This is my rewriting of the diary she left, or part of it, the part that tells how her marriage came about, up to her wedding day. To her family and friends she was known as Nelly. This, then, is Nelly’s Diary. When my brother and I used to visit, we called her Grandma, which always felt to me ugly and cold, and as soon as I became independent I thought of her as my grandmother, which at least implied belonging – of her to me. As a child and young woman, I did not know her story although I knew her, and when the diary was found, I felt she had left it partly for me.

I was born in 1945, an early baby boomer and a child of the sixties. Before I left the family home, I also lived in Croydon but on the other side of town. My father had been the one successful member of his family.

The diary: January to April 1909

My grandmother wrote the diary for herself. She does not mention sharing her feelings with anyone or wanting to, or wishing, desperately, that she could. It was her private confessional space, the place where she wrote down at the end of each day what she had done, who she had seen, how she felt, and sometimes, what other people had done and how they had treated her. Yet she did not write the word “pregnancy” or even “late;” she wrote that she was “not at all well,” “felt very queer,” or “felt so ill don’t know what to do.” The meaning of the diary is clear only to people who have been similarly afraid or who have known people who were. My grandmother did try to include my grandfather, Arthur, in her worries, but he did everything he could to push her away.

2 January, Saturday. 2.25 down (2:25 train down from London) Called at 156. Warm Baths. Spent evening with Arthur, had hard, sharp walk.

5 January, Tuesday. In bed all day, up after dinner … sent a note to ‘A’ about 6.15, he went to bed (? on purpose not to see me?) … Went up to class … came back, he very very irritable + sarcastic.

9 January, Saturday. … 2.25 down, went straight to Baths, but found them closed for repairs, home about 4, had dinner, had a wash + sat over the fire reading till 9, when ‘A’ called for me but I too tired to go out at that time, supper + to bed by 10, very very miserable

My grandmother worked as secretary to a lawyer in a London law firm and travelled to and from London every day on the train, including Saturdays, when she generally worked a half-day (“2.25 down …”). She was a modern woman for her time, spending evenings with her boyfriend, my grandfather, and going in search of him when she wanted. She lived at home in South Norwood, South London, on a street of comfortable family homes (Clifton Road, close to Norwood Junction) and was the oldest of seven children – five girls and two boys. Her father was dead, and all the children lived with their mother (“Mum”). She attended church (not every Sunday), went to choir practice and Bible study (“class”) and took part in occasional church socials and outings.

My grandfather lived at 156 Woodville Road, South Norwood, a short walk away from my grandmother’s home. He, too, lived with his family, on a rather more modest street than my grandmother’s.

Neither of them wanted a child, especially my grandfather.

Towards the end of January, my grandmother and grandfather began using what contacts they had to try to end the pregnancy. First, my grandmother made an appointment with a doctor, and Arthur went with her.

21 January, Thursday. Called at 156 about 8. Knocked 7 times, but could not make anyone hear, went over again about 9. ‘A’ in alone, asked about the dr, only stayed 1/2 hr

23 January, Saturday. Called at 156, then home to tea went to Dr Johns with A, nothing gained, back home again about 9.30.

Two days later “a friend” appears in the diary. He supplied Arthur and my grandmother with “stuff” in exchange for money. An appointment was also arranged with “a man,” although my grandmother’s courage failed her at the last moment and she did not stay.

25 January, Monday. After tea went to 156. A had been to see his friend + wants me to go tomorrow night

26 January, Tuesday. Lost 8.23. caught 8.41 foggy train late Caught 5.30 down … got ready to see ‘A’ about 20 to 8 but found he cancelled the meeting with his friend, told me trouble about £ …

27 January, Wednesday. … caught 5.46 down N.J. (Norwood Junction) 8 o’clock. ‘A’ met me, gave me some more… Dense black fog all day not lift even lunch

1 February, Monday. Called at 156 to go with ‘A’ to his friend, but ‘A’ not well, been in bed all day. Stayed with him till about 9 …

4 February, Thursday. Called at 156. ‘A’ alone, but not well enough to go out. I went alone, but when I got there could not speak to the man, so came away without, called + told ‘A,’ he very cross about it. I (do) not stop but go off to choir practice, felt very ill all day. Not enjoy anything.

In late January a dense fog settled over London, and one night it took my grandmother more than two hours to travel from London Bridge Station to Norwood Junction, normally a journey of twenty to twenty-five minutes. In February, Arthur came down with bronchitis, and my grandmother’s younger sister also became sick and had to be hospitalized. Later in the month, her mother was laid up in bed. My grandmother was tired and often felt sick and faint, and in early February she and Arthur had a bitter quarrel.

7 February, Sunday. Arthur’s birthday

In bed till 1. Little walk afternoon. Tea with ‘A’ I took him a birthday cake, spent evening with him most fervently hope + pray that God will deliver me out of his hands, he most unjust + cruel to me.

Then,

9 February, Tuesday. Went to 156 + found ‘A’ alone, he seemed only very little better. His mood much kinder to me than on Sun last, but I w’d not forgive him.

Two more meetings were arranged with the friend. In late February there was snow and cold, and in early March, a hailstorm. In the first days of March, my grandmother fell ill (“cold in my limbs”) and soon developed a bad cold and cough. She stayed home from work (“not go to biz”). But almost at once the mood of the diary starts to change. My grandmother and Arthur meet; they talk; their disagreements seem less lasting. There is a new calm, or perhaps despair has replaced struggle and the frenzied need to fight. My grandmother by then was about three months pregnant.

11 March, Thursday. Called at 156. ‘A’ + I had talk to ourselves in front room then went for a walk for 1 hr. Not go to choir practice

18 March, Thursday. … stayed at 156 little while, but ‘A’ + I very worried to know what to do for the best … very rainy night.

31 March, Wednesday. ‘A’ + I spent the evening in front room 156 making arrangements. I feel as if God really has left me to myself.

Confessed to mum, she so very good.

The secret being out, what remained were the practical details (the “arrangements”). Family and friends were “told,” and Arthur’s mother took it better than expected (“… his m. very nice about it”). A ring was bought (my grandmother put up the money) and the couple spent time at weekends with mutual friends, though Arthur’s temper did not improve. In the course of one afternoon or evening, his behaviour could change from bullying to kindness, or the other way around.

12 April, Easter Monday. Needlework sitting in garden until it rained, then called at 156. I went over after dinner, ‘A’ very horrid at first but he came round all right, we had tea together…

17 April, Saturday. 2.25 down … I promised ‘A’ to be over there 3.30, but was ½ hr late. He not ready, so came back home again … He was very, very horrid at first, but afterwards turned very nice.

I wish I knew what he really wanted, or how to manage him. It worries me so, I wish I could get right away.

23 April, Friday. Not go near ‘A,’ felt too low-spirited + done up. 8.25 down …

My grandmother noted down changes in my grandfather’s mood with as much precision as she did train times to and from London. It was as if she didn’t expect to influence him, or to be able to reason with him – and perhaps she couldn’t. Perhaps he was incapable of considering anyone’s feelings but his own. Did she know what she wrote? The clarity of her writing makes her diary a faithful record of the flux and change of an abusive relationship – of repeated movements from deliberate hurt to reconciliation, from wretchedness to hope, from anger and alienation to relative security and peace. What my grandmother describes is the emotional rollercoaster of the abused partner or wife, although she had no name for Arthur’s conduct or for her own distress. I think that she didn’t know how aberrant Arthur’s behaviour was, or how much she suffered. She was too busy keeping going and forestalling her own collapse, and writing served to neutralize what she knew and what she felt.

25 April, Sunday. 11.4 (train) to Stone Hill (a nearby suburb) Fine day, told Violet all about it, she delighted + hopes all will come right. It seems too good to be true to be as she puts it. Back to N.J. 6.40. A waiting for me, had lovely evening together, felt much brighter.

27 April, Tuesday. 8.25 down. Called at 156 saw ‘A,’ he very hard to me + cool, will not go to Vi’s on Sun.

Wish I was dead, or had never known him

The Week of the Wedding: 2–7 May 1909

Right up to the end, my grandfather fought a fierce rearguard action to protect his freedom and his purse. On the Sunday before the wedding, he asked my grandmother to sign “a paper” that presumably would have absolved him of all legal and financial responsibility for her and the child. When at the end of the week she still refused to sign, he threatened not to appear at the wedding, and my grandmother’s elder brother had to be sent round to strong-arm him into showing up. It seems as well that my grandmother’s brother Tom had not yet been told of the reasons for the marriage.

2 May, Sunday. Too late for church. Went to see ‘A’ after dinner, he rather cool + rude in manner, went home to tea + back to 156 after, he much nicer after tea … want me to sign an agreement. I refused.

4 May, Tuesday. Called at 156. Mrs. came to door. ‘A’ says all right for Sat. Mum told Tom when I gone to bed, mum say he so very upset about it.

5 May, Wednesday. … mum told me what Tom said. I think he seems very hard, says I can’t stay home. I was very upset, cried a lot + exhausted myself.

7 May, Friday. … called at ‘A.’ He wanted me to sign a very silly paper + because I wouldn’t, he said wouldn’t come down tomorrow. I had hysterics when got home. Tom went over to see “A” + came back saying alright.

Reading between the lines, it seems that my grandmother’s mother (my great-grandmother, whose name I never knew) would have allowed my grandmother to live at home after she was married. My father would then have been raised in my grandmother’s family and, just possibly, my grandmother might have returned to her job after my father’s birth. But my grandmother’s brother Tom disagreed (“says I can’t stay home”). My grandmother was the oldest child, but Tom was the elder of two brothers and male head of the household. His word was law. Three weeks after the wedding, my grandparents moved into a small flat in the neighbourhood (my grandmother paid the deposit) and my father was born there less than three months later. My grandmother gave notice at her job in the week following the wedding.

In the next seven years, my grandmother had two more children. In 1914 my grandfather enlisted in the British Army, and in 1919 he returned to England after spending a year in a POW camp with an untreated leg injury. He was unemployed from then on. At some point he became violent, and I don’t think anyone knows when. The marriage lasted forty-four years, until my grandfather’s death in 1953.

It was as a consequence of these events that my grandmother lived a life of poverty and her children were raised in an atmosphere of violence. By the time I knew her, she was also legally blind. She suffered from a hereditary blindness condition, retinitis pigmentosa, and in one brief diary entry, she wrote that she had seen a specialist who told her there was no cure.

»«

I’ve come to believe that understanding often skips a generation. My father had his own battles to fight and didn’t have much time or energy to spend regretting the hardships of his mother’s life. I was always inclined to take my grandmother’s part, and I felt that the world had treated her unjustly, even when I didn’t know the reasons for it, and even as a child.

When I first read the diary a few years after my grandmother’s death, when I was in my mid- to late twenties, the bond I felt with her was stronger than I’d imagined. Reading the diary, I knew exactly what she’d lived through, and at times it seemed that I was reading about myself – about a younger, more vulnerable version of myself. In my late teens and into my early twenties, I had been mostly ignorant of contraception and had no access to abortion. The fears my grandmother described were exactly those I had known: the terror of losing all my hard-won independence, the not knowing, the near panic at being found out.

Now when I read the diary, at almost seventy-four, I see my grandmother’s toughness. She took things step-by-step; she did not waste herself in emotional outbursts and fought back against Arthur only when he drove her almost to the ground. She recorded honestly, spoke truthfully when there was no one there to listen. Toughness was for her a practiced habit of mind.