Québec has just passed Bill 21, which bans many Québecers from holding positions of authority in the public service ostensibly to extend the appearance of ‘neutrality’ of the state. There has been a loud cry of praise for protecting secular values without understanding that the wearing of a turban, for example, is as much a part of identity as one’s religion. It was fine for Sikh soldiers to wear their turbans with pride while fighting in the trenches of the two world wars, but as Québecers today, they cannot wear these while teaching in schools or serving in the government. When the state asks for such choices to be made, smaller voices are lost in the euphoric din. My editorial is dedicated to voices that no one hears because they are not prominent enough, not loud enough. Unnamed voices that fill us with rage, force change, and cross boundaries to touch both the heights and depths of our collective selves.

This issue of Serai speaks through art, music, fiction and biographical documents. It features David Groulx’s poem, “A Breaking Open of the Belly,” an Anishnabe voice that refuses to be silent: “They cut the soul,” he writes, “from the spirit/from the body from the spirit of the earth.”

Jooneed Khan’s review of William Ging Wee Dere’s encyclopedic book Being Chinese in Canada: The Struggle for Identity, Redress and Belonging describes Chinese life in Montréal starting from 1909 when Dere’s grandfather, and later his father, immigrated to Canada. The book is an important reference to the political events that shaped the author’s life, education and career right from Loyola High School and McGill University, to Canada’s recognition of the People’s Republic of China in 1970, Québec’s Marxist-Leninist movements following the general strike in 1972, and the ensuing disappointment and disillusionment after the “defeat of the ‘Yes’ camp in the 1980 referendum on sovereignty-association.”

Himmat Shinhat in his review of Cyril Dabydeen’s collection of short stories, My Undiscovered Country, focuses on multiculturalism and how the words and voices of writers like Dabydeen have helped the shift from a focus on origins and essentialism to “a more dynamic understanding of multiculturalism” that allows for complex identities, “fluid and adaptive to the realities of a culturally and racially diverse society.”

In a multimedia piece that explores finding her true voice, Marie-Josée Tremblay focuses on pure voice and sound and how they work in music, liberation, confidence, conscience, and in the collective spirit of murdered and missing Indigenous women. “Prendre Position” is to find Loretta Saunders’ voice that continues to ask, “Did you see me?”

Sharon Bourke in her review of Louise Carson’s book, In Which, Being Book One of the Chronicles of Deasil Widdy, reminds us of the tradition of the picaresque novel. She describes how the book takes us back 300 years to the southwestern seascape of Scotland, and to Deasil Widdy, unsure of himself and his surroundings, looking for distance to escape from dark memories, for “some tranquil land he has not yet found,” while feeling throughout, Scotland’s hanging sense of “danger and suspense.

Musician, writer and educator Paul Serralheiro interviews Andy Williams and Lewis Braden, two brilliant Montréal deejays who are committed to bringing multigenerational voices of jazz and the African diaspora “to the masses,” in his article entitled “Jazz Amnesty Sound System: voices from the past speaking today’s language.”

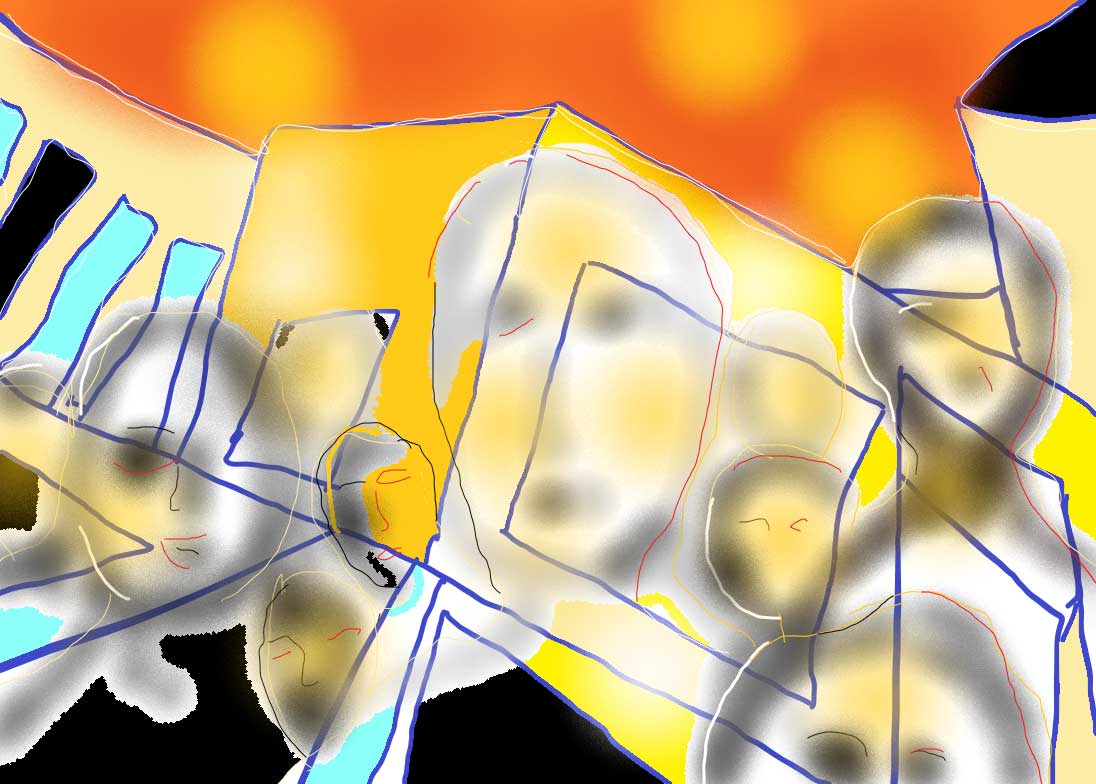

“Bodhyobumi” (Killing Field) is a photo montage with commentary created by Keya Dasgupta, Subhendu Dasgupta and Tilak Seth. The broken murtis – mangled and discarded mannequins, stripped, dismembered and flung out in an open pit in a dump yard next to a shopping arcade in south Kolkata – inspired poems in Bengali (translated into English by Nilanjan Dutta)… voices that spoke for the redesigned, discarded, dissected bodies of “writers, artists, journalists and all those / who lived to protest and resist.”

Ilona Martonfi, in her poems, “Seven Mountains,” “La Folle,” “Bleaching” and “Terezin,” speaks of the abandoned, the orphaned, the “silence back to silence,” a “plum moon / half-remembered fables,” telling stories of “a word such as children / or hunger.”

Catherine Watson in “Nelly’s Diary” goes back to 1909, the year her grandmother Nelly got married to Arthur and gave birth to Catherine’s father. Behind the veil of an unwanted pregnancy, the near impossible access to safe abortions, and the collective scorn for unmarried mothers from families and husbands “incapable of considering anyone’s feelings but [their] own,” Nelly survives in a “run-down terrace house on a forgotten street in West Croydon, the poorest part of town.” The piece is particularly relevant today when a number of states in the US are looking at the “heartbeat” bill to restrict or ban abortions.

Ami Sands Brodoff’s short story, “Will the World Pause for me?” is the soft and turbulent voice behind the faultlines of normalcy. Someone – Collier – “sweeps his arm around you and their touch is different from anyone else’s.” It calms. It is tender. It soothes. The water is cold. Collier gives you a hand. Brings you back “to the quiet of before.” The voices are gone.

Maya Khankhoje in her review of Drew Heyden Taylor’s collection of essays, Me Artsy, describes the essays, in the editor/compiler’s own words as “an exploration and deconstruction of the Aboriginal artistic spirit.” The essays range from Zacharias Kunuk, producer, director, auteur of Atanarjuat; Monique Mojicais, an Indigenous woman artist; Marianne Nicolson, an installation artist; Steve Teekens from the drum group, Red Spirit Singers; Richard van Camp, storyteller and writer; and many others. The book is “about art in general” and “performance in particular.” It is about change. Performance as Change is the theme for the next issue of Serai. Send in your submissions!