One Madder Woman, a novel by Dede Crane

Freehand Books, 2020, 360 pages

The year is 1858, the place, a Parisian suburb. A family of five is having breakfast. There is Papa, M. Morisot, the patriarch, a chief advisor in the finance ministry, his much younger wife, and their four children: Yves, the eldest daughter, 21, followed by Edma and Berthe, two years apart, and Tibby, the 10-year-old baby brother.

The manservant, Thin Louis, brings M. Morisot the mail. After reading one of the letters, M. Morisot laughs. Sent by Joseph Guichard, Edma and Berthe’s art teacher, it says: “…If your daughters are to continue under my tutelage, they will be in serious danger of becoming real artists. And in your social circle… this path would be catastrophic. I trust you understand my words and intention and heed my warning.”

Early in her accomplished novel, One Madder Woman, Canadian author Dede Crane deftly sets up its central conflicts: the difficulty that Edma and Berthe will face trying to establish themselves as professional painters in an art world where there is no place for women, and their struggles to define themselves as something other than wives and mothers.

But there is more to the scene described above. Here Crane also establishes the unequal power balance not only between Papa and the rest of the family, but also between Berthe and her elder sister, the beautiful, assured, and ambitious Edma. Berthe adores Edma; in fact, she wants to become Edma. Papa also chooses to love Edma over Berthe.

Soon we meet the hero, Édouard Manet, whose provocative and inventive paintings are panned by critics and spurned by buyers. Manet appears to be swayed by Edma’s charms, while ignoring or belittling Berthe. Berthe hates him. As well, Manet is married.

The plot moves forward on twin tracks. The author develops the love triangle between Edma, Berthe and Manet, and later, the multi-faceted affair between Berthe and Manet. This love story forms the spine of the book. The strong bond between Edma and Berthe is also central to the narrative. Alongside, Crane tells the story of how Edma and Berthe develop as artists, focusing particularly on Berthe. These strands are interdependent. Berthe is influenced as an artist by Edma and Manet. Manet as an artist is also somewhat influenced by Berthe.

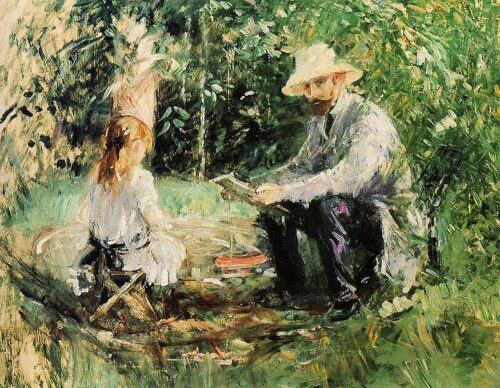

Eugène Manet and His Daughter in the Garden Of Bougival, by Berthe Morisot (1883), via Wikimedia Commons

In the first of a series of beautifully written scenes about the art of painting, we have Edma and Berthe, chaperoned by their mother, walking through the woods carrying the tools of their craft, stopping to untangle their voluminous skirts from the brambles. They have moved on from their earlier teacher, Guichard, to no less a figure than Corot (Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot), after Edma has asked “for a teacher of the new Barbizon school, one who painted en plein air, in natural light.”

They step out of the woods and wait a long time, Berthe’s impatience mounting. Then the sun rises to reveal river, trees, sky, grass and tiny wildflowers, as never before. “Can you feel them?” asks M. Corot. “These were my teacher’s words. The question less jarring than the fact that I could feel them, the colours, of course, because what else could he mean?” thinks Berthe.

The die is cast. From here, Berthe embarks on a tumultuous journey of self-doubt and discovery, turmoil and ecstasy, to become a uniquely gifted Impressionist artist. Underrated in her day (and even later, in my opinion), she would nevertheless blaze a new trail for artistic expression and for women artists.

One Madder Woman is an ambitious work. Crane dares to write in the first person, and in so doing, puts the reader inside Berthe’s skin. Her aim is to recreate the life and the incredible times of Berthe Morisot. She does so in brilliant detail, with sensuous imagery, engaging dialogue and well-developed characters, fleshing out a web of relationships. The inner world of the principal characters is also revealed through the intimate correspondence between them, given that it was the norm to write letters at that time.

Crane covers the Parisian art scene as well – the salons, exhibitions and artistic trends, and the squabbles and debates. She gives space to two major political events: the Franco-Prussian War (in which the Prussian army took Paris), and the other extraordinary event of those times, the Paris Commune in 1871. Under the Commune, Paris was ruled by a radical socialist, revolutionary government until the French army put an end to it. According to the book, an estimated 25,000 commoners were killed.

This brutal turn of events devastates Morisot, driving her into a state of depression. She finds her way out by painting, fully embracing Impressionism:

I tried to paint a leaf as it spiraled to the ground. The very instant I believed I could capture the action, I lost the quality I chased. My brush made swift stabs and feathery dashes… More intimations than objects. Temporaneous living things… The attempt to fix an image killed it dead. Movement was life… The fan was not so much a thing but an action. Life too was an action, perception, a fleeting moment of engagement… Teetering on the edge of sloppiness, carelessness, I painted the fragile, transient movements before me, their furious, hopeful colours and shadows full of grief.

Crane’s Berthe is moody and feckless, as well as questing; a woman consumed by her passion for Manet, and also defiant. She is flawed. The novel is an accomplished study in character development. Berthe goes from being a dependent sister, someone not particularly ambitious, a woman madly in love, to a principled, humane and courageous woman, devoted to her craft. This is a study of how an artist is shaped by her environment – physical, emotional, social and political. Crane also gives Manet, Edma, and the other characters their due.

Having read thus far, you may ask: how true is the book to Berthe Morisot’s life? The back of the book reveals that Crane has done her research. That said, I believe that fiction offers a world that is complete in itself. I judge this novel on the strength of its artifice alone.

It’s a thrill to encounter the now-famous artists – Degas, for example – as flesh-and-blood characters. It is also pleasurable to look up the paintings that Crane writes about in the book. (She provides a handy reference list.) One is, after all, reading in the age of the Internet.

Like Morisot’s paintings, this book is a veritable feast.