Sleep, the brother of Death

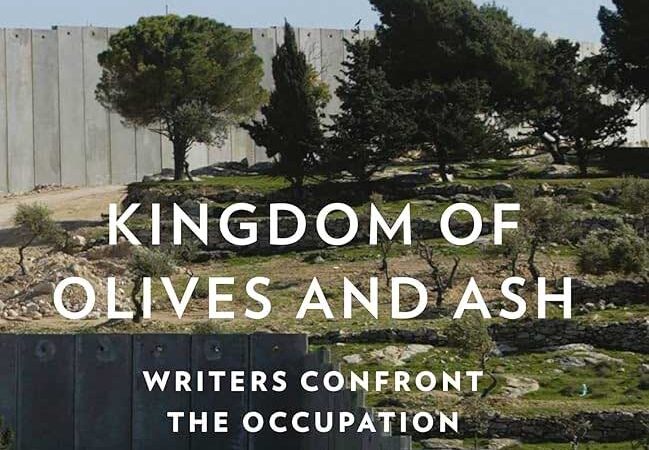

J. could not sleep. Not since the wall went up and the gates closed with a protracted metallic groan. Not since the night filled with the sighs and moaning of dozens of people suddenly filling the apartment. Not since his mother’s eyes stopped resting on him, hiding forever behind red-rimmed lids that shut, silently, that fell like heavy curtains soaked with tears cutting him off from the obsidian translucence of her gaze. J. tried in vain to lift them with gentle antics, tugging at her skirt, peering into her face only a breath away from his, as she stood huddled in the middle of that endless sadness that descended on their world. She responded with a tilt of her head, but her eyes remained hidden from him.

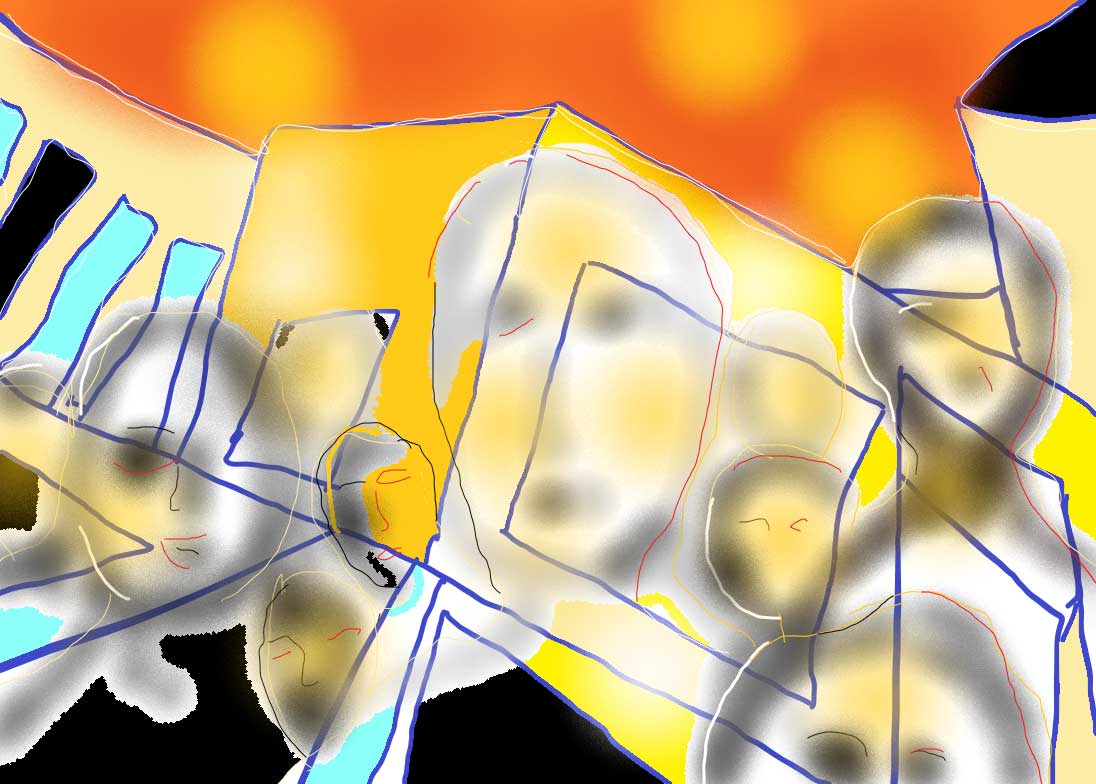

J. couldn’t sleep, as he listened to the sound that lingered behind the stifling, suffocating tightening of bodies, and the space wrapped itself mercilessly and invisibly around him. All these faces that once belonged to people he knew now sat frozen in a grotesque grimace of despair upon skeletal bodies of strangers. He could hear them in the night as they shuffled and whispered, their murmurs a prelude to the shrieking that he knew would finally erupt and the wave of pain it heralded that would swallow him. When sleep would not come and J. could no longer stand the memory of its sweetness, calling and calling, when his body twitched with millions of invisible insects that made their home under his skin, he sought solace in the night air. Creeping, meandering among sleeping bodies that littered the house, still whispering and moaning in the grip of some monstrous nocturnal beast, J. escaped into the courtyard and lifting his head to the darkened sky, a sliver of faraway calm visible from the well of crumbling walls, he dreamed of sleep. And when his eyes became too sore and the ebony firmament pulsating above him turned a murky grey, he slipped back into his corner upstairs, among the dank bodies that breathed in sobs. In the morning, alone, except for the memory of his mother’s delicate touch upon his cheek with which she checked his presence each day, J. went outside, leaving behind the aching clutter and desperate goings-on of the strangers that lived in his house, these people who seemed to know him but whom he could not recognize, and who clung with such inexplicable persistence to a life that did not want to dwell in their emaciated bodies. Standing motionless in the doorway that arched above him like a stone angel’s wing, J. watched the street, and in particular, he liked to watch the rooks.

Everything had changed but the black birds remained the same, perhaps, he thought, because they still flew over the wall and visited the old life that J. was certain existed behind it, but which for some unknown reason he was forbidden to see. The rooks emitted long raspy calls as they swooped across the sky, alighting on the cobblestones, balancing with their enormous wings that shone in the meagre sunlight. They turned this way and that, their heavy rapier-sharp beaks weighing their heads down as they sought crumbs long ago picked by the children. Frustrated, they then flew into the naked branches of the trees and carried on noisily. J. was fascinated by the way they walked, swaying from side to side, glistening midnight blue feathers dragging in the dirt, smart black eyes darting here and there. After their brief walkabout, the birds rose into the sky and were gone, and J. was alone again, alone among the strangers.

He was sorry he could no longer visit Mr. Y. who always gave him candied toffee, soft on the outside with an unexpected and resistant hard inner kernel of impossible sweetness. Not since the wall cut him off from Mr. Y.’s shop, which only yesterday was but a hop away across the cobble-stoned street and the wide pavement with cracks that he skipped over, adding up points for each he managed to avoid. Mr. Y. was dead. His mother said so, and J. tried to imagine what Mr. Y. looked like dead. Perhaps he resembled the people he saw lying motionless against the walls, oblivious to the passers-by, never moving away even as the feet of those hurrying over their bodies raised small clouds of dust that settled on their clothes and the yellow stars sewn into them. J. watched and watched, sometimes until evening fell, but they never, ever moved.

The next day they were gone, but if he ventured a little further, leaving the security of the stone archway, he soon found others. And so it was, day after day, and J. could not sleep for wondering about all these things.