I can still taste him.

After all these years, my memory of my first love is the way he tasted as we kissed endlessly on the rooftop of the Damascus swimming pool. His lips were full and smooth, quite wet, and I could feel his teeth underneath their soft flesh. We were playing ‘spin the bottle,’ and a hot rush would flush my whole body when it pointed to him as we all sat in a circle on the warm, stone floor of the pool tower. It was our secret place. One to which only the children had access, while the adults basked by the poolside beneath us, the scent of roasting shish kebabs rising in the air.

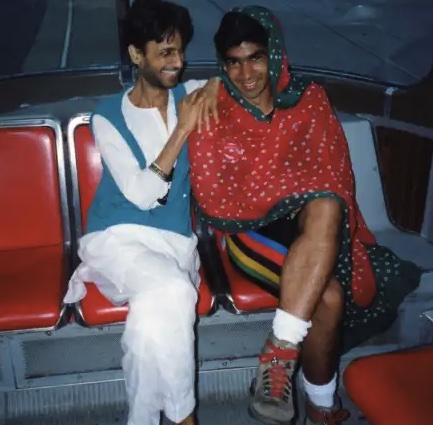

Pierre was Dutch, his father part of the UN contingent in the Middle East. I was part of a group of diplomats’ and other foreign workers’ children, with many nationalities making up the mosaic of my Syrian childhood. We were all of different ages, somewhere between 9 and 14, French, American, Swedish, German; English was our common language, and most of us attended the Damascus Community School for Foreigners, which boasted more than 30 nationalities.

We were a small group, a dozen or less per class, from kindergarten to the eighth grade. My best friend Susan was Swedish, and she taught me how to wear wooden clogs, in which she could run as fast as I did in my bare feet. We shared everything, and once she took me into her parents’ bedroom and, opening a drawer, revealed a pack of condoms. Sex was never discussed in my home, and she had to explain to me what they were.

Pierre was the oldest in our school, cocky and self-assured. Looking young for my age, flat-chested and insecure, I could only dream of getting close to him. Which did happen, occasionally. At one party, having drunk a little, he deigned to dance with me, and I remember the thrill of actually holding him in my arms, his body pressed against mine as we struggled to keep upright. As my face touched his chest, I inhaled his scent, strong and heady, the smell of a young male, new and intoxicating.

A few days later, still reeling from this, my first sensuous experience, I was sewing a button on my father’s shirt and was surprised by the same scent. It was the smell of male sweat, and the memory of it was like the key to my sexual awakening.

While I dreamt of Pierre, another boy had his sights set on me. Octavio was the son of the Brazilian consul, dark and a little pudgy; he pursued me relentlessly and steadfastly, much to my disgust. At one of the parties he cornered me against the wall and declared that I would be his one day. I pushed him away in anger. He would bring me presents, gold jewellery, a broach encrusted with precious stones, which, I later found out, he pocketed from his mother’s drawers. I often wondered what happened to this intense Latin boy with huge eyes like black coals.

But I was in love with Pierre. Far from handsome, this pouting blond teenager had a terrible hold over me and, as children would, toyed cruelly with my infatuation. Once, he persuaded Yanek, a sweet, gentle Indian boy, to trick me into thinking he was interested in me, and the experience left us both with a bitter aftertaste. Coming to class one day, I found an invitation from Yanek to a party, a personal note that implied I was to be his date.

When I arrived, all the other children were already there, waiting, giggling. There was no date. And Yanek was standing against the wall, suddenly as aghast at the deception as I was. Laughter broke out and reverberated across the room, and I cringed, desperately trying to hold back my tears, horrified and humiliated. And at the same time, I could see Yanek’s face, almost as ashen as mine, for in some way he, too, had been made fun of, a puppet in the hands of the other children, a citizen of a second-class country, a lower caste. Like me.

He must have apologised to me later, I’m quite sure. Although, strangely, I never held it against him. Nor against Pierre, the instigator.

My revenge came later and with no premeditation, as if fate had decided to grant me a reprieve. The so-called Six-Day War in the Middle East, in 1967, changed me imperceptibly, ripping into my colourful, idyllic childhood and, aided by my imagination, infiltrating it with an apocalyptic vision of a world war.

It started innocently, albeit abruptly, as I enjoyed a mid-class recess, playing tetherball in the green compound of the school. Suddenly, limousines from the U.S. embassy appeared at the gates, and all the American children were whisked away. Soon cars with British diplomatic plates arrived to collect my English playmates, and a sense of unease gripped the rest of us. We filed into our principal’s office, and found Madame Bitar listening intently to a small transistor radio. She said something about a dangerous political development and urged us to collect our things and go home.

We had been preparing for the possibility of a Middle-Eastern war for some time, hiding under our desks when the warning alarm sirens would go off, getting used to the darkened city with street and car lights painted blue, as Damascus readied itself for Israeli air raids.

But I was not prepared for what awaited me outside, as I left the school. A different world than the one I left that morning, with streets emptied of regular citizens usually milling about in the bright Syrian sun, replaced instead by groups of frenzied young men with guns, shooting into the air and crying ‘war, war.’ Fear gripped my throat and I began to run home. Halfway there, I came upon my father, driving, panicked, to pick me up from school.

After a brief family conference at home, it was decided we would go to check on the wife of my parents’ architect friend, who was alone with a small child and pregnant with another, her husband away on a business trip. As we sat in her garden, tense and uncertain as to what awaited us, with my father predicting the worst as usual, the worst happened. A sudden, thundering bang shook the ground as Israeli fighter planes appeared overhead. There was no warning, no sirens, as bombs rained on Damascus airport on the outskirts of the city.

We hurried into the middle windowless room of the house and waited as the bombing continued. Incongruously, the sun kept shining, the heat filtering into the darkened room, nature oblivious to the sudden invasion, while thoughts of the end of the world paralysed my body and mind.

Suddenly, it was all over. Then, after a brief silence, the sirens went off, wailing across the city in a belated alarm. When they stopped, we ventured outside to find the streets quiet and deserted under the blazing afternoon sun. As we made our way home, we came upon a long, winding convoy of white UN cars ready for departure.

I imagined I could see Pierre in one of them, his face glued to the window.

For the next six days, we stayed at home, obeying the curfew that gripped the city as the Israeli army stood at its doorstep. The tension was tangible, and I would hide in the kitchen, kneeling on the cold, marble tiles, my elbows against the rough wicker seat of a small stool, praying and praying: ‘Please God, make sure it’s not the third world war, please God, please.’

Outside, in the apartment, Arab children cried, and our cats hid fearfully under the bed. Several families, following a government edict in view of continued bombardments, moved from upper floors to stay in our street-level flat, and it was hard to find peace among the chatter and disorder of all these people locked together.

Despite the frequent bombing, young boys oblivious to the danger ventured into the streets, looking at the planes swooping down and picking up fragments of shells, their recklessness a constant amazement to my ever-weary father.

When it all ended, I returned to school with my Swedish friend Susan, to find it strangely empty. Madame Bitar was still the principal, and the classes continued, now under the aegis of the Italian embassy. The American and English children never returned, their nationals no longer welcome under the new political order. But the Dutch were back, and so was Pierre. He had not changed much. I, however, had grown into a young woman of 13. No longer the ugly duckling, I now wore a bikini to the pool, although I still had to stuff tissues into my bra.

I remember the precise moment Pierre ‘saw’ me for the first time since the war. I was swinging on the high swing in the play area, soaring above the sand, higher and higher. I pretended not to see him as he approached and stopped to look at me from the sideline. Still painfully aware of my immature body, I kept my gaze firmly on the blue sky, watching him from the corner of my eye.

When I finally descended, he approached me and said ‘hello,’ something he’d never done before, usually waiting for me to make the first move.

Soon our little group was back on the rooftop, spinning an empty Coke bottle, pairing off to kiss in the corners, sand gritting between our teeth as our lips locked in deep and exhilarating yet innocent embraces. But I didn’t care anymore if the nozzle slowed down before him, although we continued our furtive affair for some time before breaking it off.

He still tasted the same.