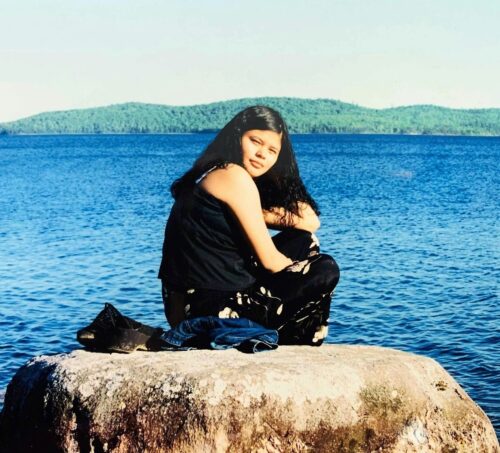

Joyce Echaquan on her Atikamekw ancestral territory in Manawan, July 1999 – Photo by Alice Echaquan, via Wikimedia Commons

[Serai editor Jody Freeman interviewed Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand from the Atikamekw Council of Manawan in early January 2022. The Council of Manawan and the Atikamekw Nation Council spearheaded consultations in the Atikamekw community and the larger Québec community, in the wake of Joyce Echaquan’s grievous death at the hands of racist healthcare staff. The results of these consultations were forged into a concrete plan of action: Joyce’s Principle.[1]

“Joyce’s Principle aims to guarantee to all Indigenous people the right of equitable access, without any discrimination, to all social and health services, as well as the right to enjoy the best possible physical, mental, emotional and spiritual health.

Joyce’s Principle requires the recognition and respect of Indigenous people’s traditional and living knowledge in all aspects of health.” (Excerpt from Joyce’s Principle)]

Joyce Echaquan’s courageous spirit infuses this call to action launched by her Atikamekw community in November 2020, just over a month after her death. Seared by grief, shock and outrage at the racist mistreatment and abuse Joyce suffered in the final days of her life in a Joliette hospital, the Atikamekw nation resolved to lead the way to sweeping changes. The cultural shift it is urging governments, educators and civil society to make is nothing short of ground-breaking.

The Atikamekw people are holding up a multifaceted vision of health, respectful social services and inclusive education that recognizes and honours Indigenous knowledge, practices, culture and needs. And they are proposing tangible steps to get us there.

They are calling on people at all levels of society to adopt Joyce’s Principle and pledge to take action to make it a reality: governments, educators, professional orders, workers and managers in health and social services, and all concerned members of Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities in Québec, across Canada, and beyond.

Serai: Your community of Manawan and the entire Atikamekw nation seem more and more determined to press forward with this plan of action. It has been less than a year and a half since Joyce Echaquan died. What progress has been made since you consulted your community and the public, and submitted your brief to the Québec government and the federal government? Was it in November last year that you called on them to adopt and implement Joyce’s Principle?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: It was in November of 2020.

Serai: What progress have you seen so far? Did the federal government pledge to endorse Joyce’s Principle?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: Yes, the federal Liberal government is developing draft legislation that follows the recommendations set out in Joyce’s Principle, which is a positive step for the cause.

Provincially, Joyce’s Principle is still being met with a certain degree of distrust on the part of the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) government. But at the grassroots level, among organizations and those willing to work as partners, people are very open. There is extensive grassroots support. I think this is the way we can bring about social change and transform our society to collectively address systemic racism.

We have learned a lot of things from the tragic death of Joyce Echaquan on September 28, 2020. And in the period since her death, I think the realities of Indigenous peoples have now been put on the agenda in all regions of Québec and across Canada.

The issues of Indigenous health are on the agenda, too. The process has been traumatic, but now it’s clear how the anger felt by the community of Manawan is being expressed – not to destroy things, but to bring about change and propose solutions to the problems. This is what we’ve seen in the spirit of Joyce’s Principle.

Historically and culturally, the Atikamekw nation has always been peaceful and has tried to maintain harmonious relations with everyone and interact in harmony with other nationalities. If we want to bring about social, political and cultural change, what the Manawan community and the Atikamekw nation is proposing with Joyce’s Principle will be beneficial for everyone.

I think the federal government realizes how important this Principle is to pave the way for changes to be made across the entire country. That’s why the mandate* given to the new minister for Indigenous Services Canada – to ensure that Joyce’s Principle is implemented in practice – is so important. This mandate bodes well for our community and for the office overseeing Joyce’s Principle, and it is also a positive step in changing attitudes and social consciousness about Indigenous peoples, and in improving the health situation. (* “Fully implement Joyce’s Principle and ensure it guides work to co-develop distinctions-based Indigenous health legislation to foster health systems that will respect and ensure the safety and well-being of Indigenous Peoples.”)

Serai: I understand that the government of Canada has granted $2 million to the Atikamekw nation to help advocate for Joyce’s Principle and see that concrete steps are taken. Have those funds actually been transferred?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: Yes, the funds have been received. With the office overseeing Joyce’s Principle, we’ve developed an action plan to move forward in getting the Principle applied in practice.

Serai: The Québec government has stated that it accepts the recommendations in Joyce’s Principle but can’t endorse the overall Principle because it doesn’t agree with the term “systemic discrimination.” Does this position give you anything to work with?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: In our exchanges with the Québec government on Joyce’s Principle, the government spokespersons made a declaration that they didn’t want to adopt the Principle. Some opposition parties presented a motion to have Joyce’s Principle adopted by the Québec National Assembly, but the government dismissed it.

We see why the government doesn’t want to get involved in a statement that recognizes systemic racism. But if it recognizes the problem, concrete solutions could be put in place. If it refuses to recognize the problem and uses band-aid solutions to patch things over, the situation will never change and neither will our collective consciousness. Political leaders are going to have to change, too, in the way they approach Indigenous peoples’ relationship with the various systems.

Serai: I read that some nurses’ organizations and the school of nursing at McGill University formed a coalition (Regroupement infirmier en santé mondial et autochtone (RISMA), École des sciences infirmières de l’Université McGill-INGRAM, Infirmiers de McGill pour la santé planétaire, Association Québécoise des infirmières et infirmiers) and submitted a professional opinion and recommendations to the Québec Order of Nurses to initiate “cultural safety training” to ensure that Indigenous people receive the health care and social services that they need. I don’t know if they have succeeded in getting that passed with the Order of Nurses.

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: I know that there have been internal discussions at the Québec Order of Nurses, and its Board and the members’ assembly are preparing to adopt Joyce’s Principle. That is a positive step towards reconciliation, and in changing practices with Indigenous communities. It’s very positive.

Serai: The nurses’ coalition also recommended that the Order of Nurses offer professional development courses based on a program developed in British Columbia, called “San’yas Anti-racism Indigenous Cultural Safety Training.” That training program was initiated in 2008 in BC, I think, and was subsequently adapted in Manitoba and Ontario.

Another recommendation by the nurses’ coalition was that the Order set up an interactive online training program for all nursing personnel working in health and social services in Québec, and that the program be adapted to each of the 11 Indigenous nations in Québec. The idea was to ensure that each Indigenous nation be involved in designing and adapting the training courses.

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: That is part of our recommendations and the call to action in Joyce’s Principle – to truly collaborate and create partnerships with the indigenous communities that are close to these organizations. This is an objective that we have to keep putting forward, because in Québec there are 11 major Indigenous nations, and in the regions, a variety of approaches have to be developed. Why not have these partnerships create training programs that are tailored to each of the Indigenous cultures in these regions?

Serai: Could you talk a little more about the concept of cultural safety? I read that it was developed by Maori nurses in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: That’s an interesting concept first developed by Indigenous nurses from the Maori community in New Zealand, who were coming up against racism and various considerations that were not part of their Maori culture. In Canada, this concept emerged in the 1990s or early 2000s, and much later in Québec.

This approach creates a new way of working in relation to Indigenous people’s health. It involves recognizing their history, recognizing their territory, and acknowledging their spirituality, too – because in Indigenous cultures, health refers to more than just our physical health. It includes our emotional health, our mental health, our relationship with our ancestral territory, of course… and our spiritual health.

It was from this holistic perspective that the Maori reflected on the concept of cultural safety and how to work to improve the health of Indigenous people.

Serai: In Joyce’s Principle, you also talk about Indigenous peoples’ right to preserve their traditional healing practices and their medicines. What does that cover?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: In terms of cultural practices, this often refers to traditional medicines – medicinal concoctions that are plant-based (using roots, bark or leaves), or animal-based. There are special ways of preparing these traditional medicines, and it is important to recognize the ritual or ceremony involved in their preparation. Today I’ve talked about the relationship with our territory and the land, but this also means recognizing that we have a relationship of reciprocity with the plant world, the animal world, and the spiritual world.

This relationship is what we are defending when there is deforestation due to logging operations, for example. Indigenous people are seen as the ones blocking these logging groups, but in essence, it is this relationship that we want to preserve – the respect we have with the land and our ancestral territory. For the companies, it’s an issue of money, but for us, it’s our medicines that are on that territory. We have to protect the territory to be able to retain and preserve our traditional medicine. There are elders who know a great deal about these medicines and pass on their knowledge. It is important to recognize these practices.

Serai: What will it take for the Québec government to move forward on Joyce’s Principle? Do you think the impetus is going to come from civil society? Individuals and organizations like unions, professional orders, community groups, teachers? How do you see this change happening?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: To get the government of Québec to change its position, we have to look to Quebecers and Québec organizations, professional orders, community groups, etc. They are the ones that are going to be reaching people. We know that 2022 is an election year in Québec. That’s another way to shake things up and put pressure so that the next government is able to endorse Joyce’s Principle. It’s going to take a social and political campaign.

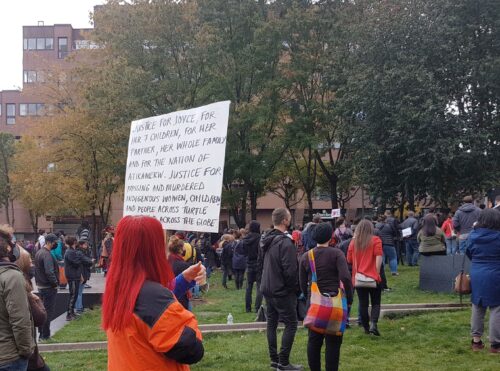

Justice for Joyce: demonstration in front of the Palais de Justice courthouse in Trois-Rivières, June 2021 – Photo by Thérèse Ottawa, via Wikimedia Commons

Serai: In terms of the opposition parties, what positions have Québec Solidaire and the Québec Liberal Party taken?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: Both have expressed support for Joyce’s Principle. The Québec Liberal Party presented a motion in the National Assembly to adopt Joyce’s Principle, but the CAQ government refused to table it.

It’s going to be an important election for the whole set of issues put forward in Joyce’s Principle, raising the level of debate on what the government calls “semantics” (about defining systemic discrimination)… But it is also a social debate that we’re confronting with Joyce’s Principle. A government has to be responsible for its citizens, and responsible for the services it wants to offer Quebecers.

The election is going to be a major opportunity to raise the issues in Joyce’s Principle, and the political parties will want to join the movement and attract Indigenous voters – providing the Québec Liberal Party and Québec Solidaire will fight to ensure that Joyce’s Principle is at least adopted by the next government, and at best, that it is adopted and implemented.

Serai: In the meantime, if people working in health and social services can get their professional orders to adopt Joyce’s Principle and start to apply it in their training programs, their professional development programs, and continuing education programs, that could start to change things in the next year, couldn’t it?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: Yes, we strongly encourage that. Joyce’s Principle has a section recommending that not only professional orders but also universities and colleges offer healthcare programs that include mandatory courses on Indigenous issues, and Indigenous cultural safety training in particular. With these courses, it’s important to be able to really understand what cultural safety means and the realities that Indigenous people face. If these courses are offered as compulsory components of the program, one of the problems is already addressed.

Also, some professional orders are developing (culturally sensitive) training for professionals in their field. They are key partners in effecting changes in practices that involve training techniques, on what approaches to take in working with Indigenous individuals or individuals from another culture. These initiatives are important and we encourage professional orders to contact our office or the Indigenous community concerned, to develop these kinds of training programs.

Serai: Could you summarize the main recommendations in Joyce’s Principle?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: The first recommendation deals with the relationship between Indigenous people and the Government of Canada in regard to health and social services.

The second focuses on the relationship between Indigenous people and the Government of Québec, and includes a measure proposing that Québec appoint an ombudsperson to deal with Indigenous health and social services.

The third recommendation centres on the relationship between Indigenous people and the public, in regard to health and social services.

The fourth addresses the relationship between Indigenous people and teaching institutions in the fields of health and social services.

The fifth specifies the relationship between Indigenous people and professional orders in health and social services.

And the sixth recommendation focuses on the relationship between Indigenous people and health and social services organizations.

There are concrete measures proposed to implement each recommendation. At the political level, the objective is to adopt legislative measures to implement Joyce’s Principle in practice.

The measures to improve the relationship between Indigenous people and the public focus on publicity and public education to raise awareness of Indigenous people’s realities. It is important for our society as a whole to understand, so that people can stand up against racist acts.

In universities and colleges, the key steps are to develop specific programs like cultural safety training, and to work together with health professionals who are Indigenous. There are Indigenous doctors, nurses and specialists who can contribute to the process. This is also what we’re encouraging the professional orders to do.

Serai: There’s also the aspect of hiring Indigenous people to ensure representation in designing the training programs and in decision-making.

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: It’s important to decolonize our minds and our approach, to really create an openness and willingness on both sides to work together.

Serai: In terms of encouraging more Indigenous students to get involved and continue their studies, and have a positive experience studying, what progress is being made?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: Laval University and Concordia University took the initiative some years ago to create offices specifically for Indigenous students. They are setting an important example for other universities to meet certain objectives and develop forms of reconciliation with Indigenous students.

Speaking from my own experience, as a graduate of Laval University and former president of the Indigenous students’ association, I’m happy to see how far this university has come now, with a specific action plan for Indigenous students.

Serai: It’s impressive. The fact that you and others were there, working with the Indigenous students’ association, and that Michèle Audette was there – all those efforts have really moved things forward. When the obstacles are finally removed, changes can happen faster than we think.

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: We have a lot of hope for the coming years.

Serai: Joyce’s Principle seems to be centred on relationships – everything in it is about relationships. That’s hardly a foreign concept to non-Indigenous cultures, but if the tendency is to focus on work or on making money, the whole idea of reciprocity, relationships, and the time that is required gets pushed to the side.

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: I think this is what has to be restored. When a Quebecer has to see a doctor, the doctor’s time has to be considered so that a relationship can be established with that patient. Today, everyone is going at such a fast pace that this relational aspect of life is disappearing. What we are proposing will help rebuild these human (and humanistic) relationships.

Serai: Sipi, can I ask how long you have been Vice-Chief for the Council of Manawan?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: Since August 2018. Not that long. Before that I worked as a political and legal analyst for Femmes Autochtones du Québec (Québec Native Women). That was during the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

Serai: So you knew Michèle Audette at that time?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: Yes.

Serai: You’ve seen a lot – even though you’re very young (laughing).

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: I’ve travelled a lot, too, so I’m familiar with Indigenous issues, and those experiences have given me a lot. That’s what I want to share in my community and with my nation.

Serai: This exchange with you has been very touching for me, Sipi. Is there anything else that you’d like to share?

Vice-Chief Sipi Flamand: If the Québec government adopts Joyce’s Principle, there will be a new relationship created with Indigenous communities.

[…] Thank you for this opportunity to advance the cause, and especially among English-speaking communities.

To find out more about Joyce’s Principle and pledge your support, please click here.

To contact the Atikamekw office overseeing Joyce’s Principle:

Website: Joyce’s Principle / Principe de Joyce

Facebook: Principe de Joyce

Instagram: principedejoyce

[1] Years of thought, consultation and struggle are reflected in Joyce’s Principle, distilling the wisdom and experience and heart of the Atikamekw people and other Indigenous nations, communities and individuals in Québec, Canada and other parts of the world.

To name some of the most recent efforts:

– the Assembly of First Nations Quebec-Labrador’s Action Plan on Racism and Discrimination issued on September 29, 2020, the day after Joyce Echaquan died;

– the testimonies of over 1,000 First Nations and Inuit people for the Viens Commission, whose report in 2019 roundly denounced the systemic racism they face in accessing public services in Québec;

– the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, from 2015 to 2019, exposing the centuries-long colonial legacy of normalized violence against Indigenous girls and women;

– the fight for legal recognition of Jordan’s Principle in 2016 for Indigenous children in Canada, in honour of Jordan River Anderson in Manitoba;

– the longstanding efforts of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada from 2008 to 2014 to uncover the truth about the Indian residential school system.

Joyce’s Principle is the outcome of deep collective considerations and dreams.