The Monarch butterfly can travel up to 2,500 miles across “borderless” lands to seek warmth and nourishment for its larvae. The wildebeest journeys through the Serengeti forming part of the largest mammalian migration in the world. And the Arctic Tern, known to undertake the longest migration in the animal kingdom, can fly as far as 55,900 miles to find nesting spots in circumpolar regions.

In this issue of Montreal Serai, Mirella Bontempo (book review, Norman Nawrocki’s Cazzarola! Anarchy, Romani, Love, Italy: A Novel) refers to Latcho Drom (“Safe Journey”), Tony Gatlif’s French documentary film on the thousand year old migration of the Romani people from India to Europe. The film starts with a young Kalbelia boy singing out to the sand-filled air of the Thar Desert:

“I want to go back to my family

And run barefoot

Cover my feet with the leaves of a tree

And my body with delicate foliage…”

And a Romani woman in Hungary sings to herself on a train:

“The whole world hates us

We are cursed

Condemned to wandering throughout life…

We survive as hounded thieves

But barely a nail have we stolen.”

In Citizen or Stranger (Aljazeera, Point du Jour), Sarah, a French citizen, born in Somaliland, responds to whether or not she would like to stay in France:

“I’ve wanted to leave for a long time. My whole family is in England. But wherever we go, even in Somaliland, my children ask ‘when are we going home?’ For them, home is here, but is this really their home? I don’t have an answer to that. It’s up to the French to say whether they are at home or not.”

This issue is dedicated to migrations – powerful evidence to human and animal survival. It is also a tribute to Serai, a place of rest for those from away – a place for margins to fold and re-fold to form a new centre.

In Canada today, only about five percent of the population has descended from First Peoples or the original inhabitants of the country. These include the Inuit who, according to some anthropologists, made their way from Siberia to Alaska across the Bering Land Bridge, a migratory pathway. After the ice age and the subsequent rise in sea levels, the connection between Asia and North America was cut off, leaving migrant human and animal populations stranded across oceans. (Virtual Museum Canada, http://www.sfu.museum/journey/an-en/postsecondaire-postsecondary/pont_beringie-beringia_bridge)

All non-Aboriginal populations in Canada migrated from other lands: some looking for wealth and opportunity, and some for adventure. A significant number, however, came here as a result of being displaced from their homelands. They are among one in hundred of the world’s citizens forced to migrate because of conflict, political upheaval, violence, disasters, climate change or development. The figure is rising, and most migrants are either in “protracted displacement situations or permanently dispossessed.” Although the cost to the international community and the sheer numbers are compelling enough, it is the human cost of forced migration that is far more difficult to assess and address. There are “destroyed livelihoods, increased vulnerability especially of women and children, lost homelands and histories, fractured households and disempowered communities, and the destruction of the common bonds and shared values of humanity.” (World’s Disasters Report 2012: Focus on Forced Migration and Displacement, IFRC, Geneva 2012, P9)

On the other hand, receiving communities and countries have tightened restrictive regulations in a post-9/11 world. Since most forced migrants do not meet legal requirements of receiving countries, they resort to illegal and desperate ways of entry, further legitimizing the “securitization of asylum.” Boatload after boatload of men, women and children are turned back to hostile seas and lands, leading to a human disaster of unparalleled proportions that few are prepared to cover or address.

This issue comments on the Quebec Charter of Values, a new bill tabled to make those that can be identified by color, clothes, food, practices, and accents feel that they somehow do not belong. It is perhaps because they wear a six-yard cloth around their heads or a mysterious veil that hides their hair or face. For reasons such as these, and since they look as though they cannot assimilate, it is argued that they should not be allowed to represent secular Quebec in the public service. The Charter of Values over which a provincial election has been called, would make it more difficult for minorities to work in the province, would make them feel unwelcome, and as Joyce Valbuena writes in her piece on migration, feel disrespected. It is the question Farida asks herself in Maya Khankhoje’s story, “Taking/Removing the Veil.” What is it that makes someone feel proud for what she is and what she stands for? The right not to believe can co-exist with the right to believe or to semi-believe. The Charter of Values, following the issues around “reasonable accommodations,” has created deep divisions, and can potentially lead to unprecedented, government-sanctioned racial discrimination.

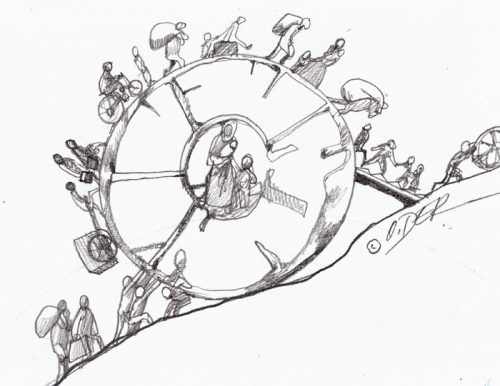

There is a broad range of articles including, among others, Pietro Ferrua’s short story in Italian, “Le caramelle dei banchieri;” Jaspreet Singh’s interview with Jaswant Guzder, a Montreal-based psychiatrist and visual artist; Patrick Barnard’s scan of the history of human migration and common stereotypes; Richard Swift’s interview with Joan Martinez-Alier on the economics of development and Degrowth; poems by Ilona Martonfi and Anna Fuerstenberg; and book reviews of Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Lowland and Vinita Kinra’s Pavitra in Paris. Art works from illustrators such as Oleg Dergachov eloquently express, through delicate sketches, the essence of the concluding words from Patrick Barnard’s “The Moving Other:”

“In the Twenty-First Century migration is one of the keys to the world we are making and that also is shaping us. We must see it for what it is. To “look for stereotypes,” to borrow the words of anthropologist Mark Blaker, is both unwise and dangerous. Instead we must be ready to appreciate, as Blaker puts it, that “what we discover is not precisely what we expected.”