The Situation

The McGill University Health Centre at the Glen (the MUHC) is a mega- complex on the western edge of downtown Montreal. It is the agglomeration of a number of hospitals into one immense entity: the Montreal General, Children’s, Chest Institute, Royal Victoria, Neurological Institute, and Shriners’ Hospital, as well as research facilities. Each has a dedicated pavilion. They are strung together by a grand curving concourse. The whole is surrounded by the residential districts of Montreal’s South West, the borough of Notre Dame de Grâce, and the municipality of Westmount.

The oblong site for the MUHC presents design challenges but offers at the same time numerous opportunities. Its southern edge runs along the St Jacques escarpment while its northern edge is bounded by commuter railway lines. To the west it is defined by Decarie Boulevard. At that border the St. Raymond neighborhood of NDG begins. The eastern side abuts a deep gulley called the Glen.

The creation of this project involved a generation of planning and a huge amount of public money invested by the Quebec government. Now that the complex is approaching completion, it is time to step back and assess what it means, not just for Quebec, but for urban planning in North America. Governments are expected to have a vision of where their respective societies will be in the future. This vision should draw upon current trends and on the needs of its citizenry. Thus a responsible forward-looking vision is of paramount importance when enormous investments from the public purse are called into play. And it is of even a higher order when a particular investment involves a public institution that is a leading-light in what represents a healthy lifestyle. With a construction budget of nearly $2 billion and its primary goal being that of health, the MUHC fulfills all these requirements.

Unfortunately, the MUHC Glen does not project any of the 21st century vision that I would call the Urban Enlightenment, a concept that fully engages urban design and architecture so that cities become truly liveable and sustainable, taking the human frame as reference. This kind of planning runs counter to many ideas espoused in the 20th century. Then the prosperous middle class was encouraged by expressways, real estate markets, and advertising to relocate to the suburbs. The city was seen as the engine of prosperity but little more. The suburbs required large tracts of land, often of excellent agricultural quality, tremendous public investments in road construction and providing services because of their dispersed character. Suburban life involved driving to every need. It often reduced culture to the television set. Gratification came from sequestering into the tranquility of the pseudo-villa, the bungalow. The burgeoning suburb of Mirabel north of Montreal is an on-going example of that 20th century dream.

The nefarious aspect of the suburbs is that because of their low density they make public transit unsupportable, and because there is no reliable public transit, the suburbanite requires a private vehicle. Then the ever increasing number of suburbanites using their vehicle to gain their living in the city continues to degrade the urban environment. Such degradation causes more city dwellers to move out into the suburbs thus increasing the volume of cars entering the city. This is the vicious circle of degradation imposed on cities by their suburbs.

In contrast, the 21st century Urban Enlightenment calls upon continuity and density in housing, integration of public transit into all construction schemes, the use of built form to capture ambient energy, the creation of urban spaces that are social places, interconnected parks and ways that allow every citizen nearby access to Nature, a range of institutions, each of which is well integrated into the urban fabric, and a full palette of cultural events. It is a concept that has the potential of taking the urban experience as created by the ancient Greek polis or the Renaissance city state to another level.

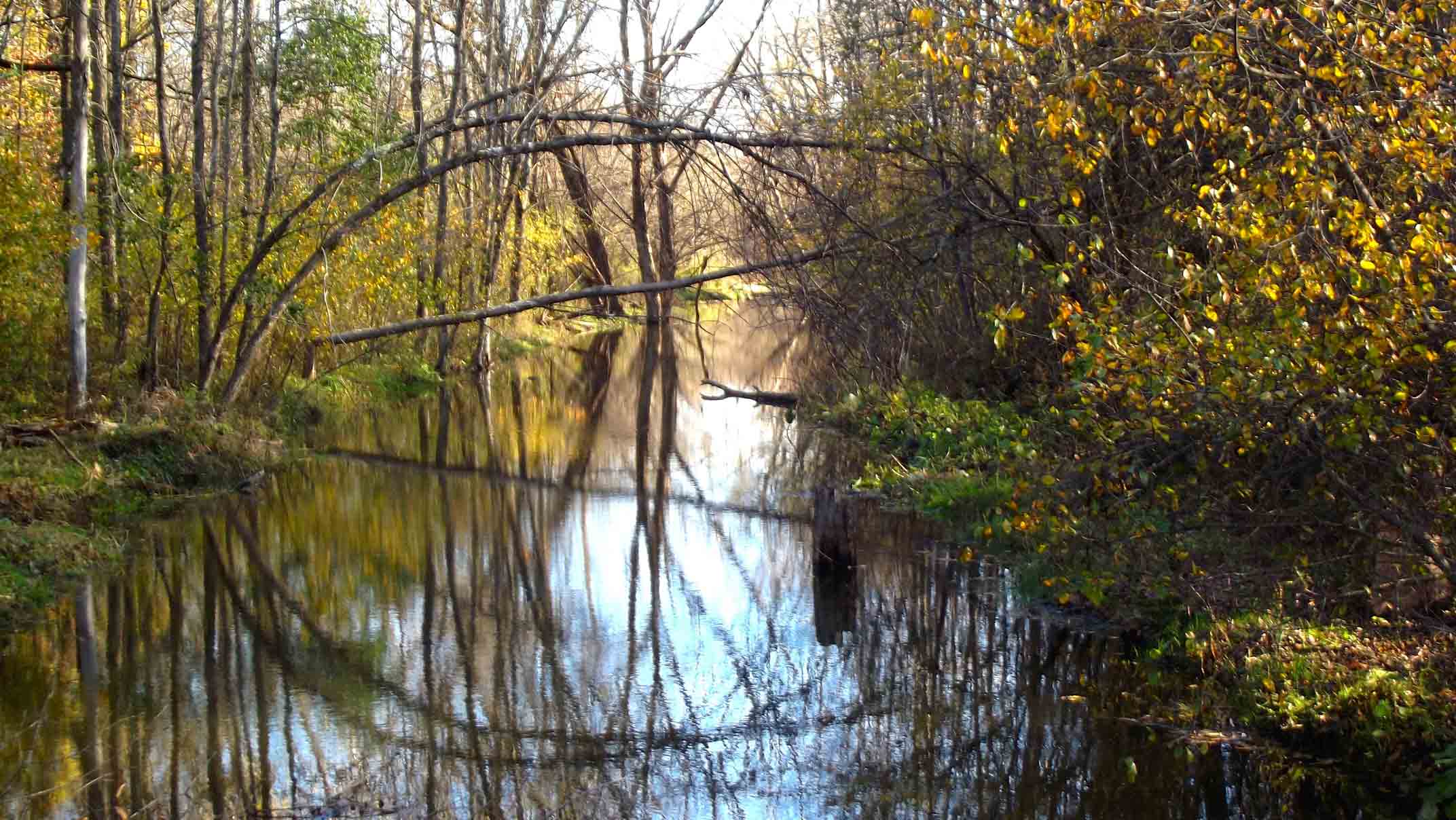

But there are basic implications of the Urban Enlightenment. In the first place, it is of paramount importance that it be centred on the Human Scale. This means that the end result of design should be a heightened sense of well-being and meaning for each citizen in the urban spaces that are created. These spaces must not be dominated by traffic. In fact, traffic volumes within cities must be significantly reduced. Quite simply, urban life does not revolve around the car. Secondly, it is crucial to construct the city so that it approaches a balanced harmony with its natural environment. This could be accomplished be a network of parks and greenways. Frederick Law Olmsted — the very man who designed Parc Mont Royal — demonstrated a century ago the many different ways in which this can be done. His schemes for The Emerald Necklace of parks in Boston, the interconnected parks and greenways across Buffalo, and the Riverside community of Chicago show how Nature can be woven into the city, how the city dweller can more easily approach Nature. He drew upon the particularities of Nature found in each locale. Thirdly, it is imperative that emerging technologies be employed so as to decrease the consumption of energy while securing the standard of life which we know. They must also be used to capture ambient energy, whether that be solar, wind, or geothermal. This is a major component of what is meant by the intelligent city. All three of these principals of the Urban Enlightenment demand sophisticated design.

Given this conceptual framework, how and why does the MUHC fail?

The Failures

1- The MUHC did not integrate itself into all public transit adjoining the site. Instead it blinkered itself within a car-centred solution.

It has been said that the Glen site for the MUHC is one of the places in North America most perfectly connected to public transit. Four transportation vectors immediately adjoin it. The Vendôme train station, the Vendôme métro (subway) station, a terminal for west-end bus routes, and Montreal’s east-west cycling path are all along its northern border. It is a most fortuitous situation. MUHC Spokesperson Jonathan Goldbloom some time ago stated that this was the deciding reason for choosing the Glen site.

Yet the MUHC turned away from these existing transportation vectors and actually minimized their integration. The connection to this intermodal hub at Vendôme has been designed as a small tunnel leading to the underground parking garage of the complex. It is an ungainly and inadequate solution. It is not even barrier-free.

Other possibilities were available. It is obvious that all planning for the MUHC should have begun from the hub itself. The air rights over it could have been procured. Then instead of a tunnel leading to a parking garage, such a leading-light institution could have had stairs and elevators ascending from the métro and train platforms, and bus arrival area, upwards to a walking concourse that would connect to the pavilions. Moreover, placing the centre of a curving concourse over the intermodal hub would decrease the average walking distance to a pavilion by half.

Instead the MUHC closed its eyes to this intermodal hub. It did not consider the urban solution but chose to build a ring road joined to underground parking levels. It is a suburban solution, comparable to a shopping mall. Why the MUHC blinkered itself into seeing vehicular infrastructure as the predominant means of access is not known. But what is especially incongruous with this design approach is that Montreal has all the public transit facilities built and awaiting use by the MUHC. The resulting disregard of the Vendôme intermodal hub might be seen as design malpractice, and a rejection of any kind of civilized urbanity.

The MUHC design certainly runs counter to ideas of Urban Enlightenment wherein vehicular access is an equal partner in a triad that includes active transport and public transit. Instead, what we now see at the MUHC is a carry-over from the 20th century conception of the city as a vast grid for vehicular traffic flow whose price is human exclusion from its urban space. Extreme cases of this type of planning have led to donut cities wherein dormitory suburbs surround empty cores. Of all the modes of transport, it is the car that most degrades the urban environment. At the same time, car-dominated transport stimulates growth of low density suburbs. For liveable cities, the exclusive expenditure of public monies on vehicular access infrastructure is a lose-lose situation.

2- The MUHC Glen failed to integrate with its surrounding communities. Instead it has become an island of isolation.

Hospitals are welcoming to the communities they serve. And this has certainly been true of those hospitals that are now joining to become the MUHC. As separate entities, they have previously integrated well with their surrounding neighborhoods. Yet once joined into the MUHC they will be isolated just as the ubiquitous shopping mall is isolated from surrounding neighborhoods.

Most apparent will be the lack of a viable connection to the South West borough. The MUHC Glen sits on a flat plane whose southern edge is an escarpment. The South West is below it. A vehicular access route on the diagonal across that escarpment has been built. It serves delivery trucks and staff commuting by car. A multi-storey parking garage abuts this route.

During the last two years in a number of consultations citizen groups advanced the idea with MUHC officials to use the opportunity of this new access road as a means of solving the isolation of the South West. The MUHC had been lobbied for a pedestrian sidewalk under an arcade and a protected cycling path to parallel this road. Citizens also asked that the elevators of the parking garage be made accessible at ground level so that there would be a barrier free means of access. These ideas were considered, managed, and shelved. Thus the lack of walking and cycling paths from the South West along with barrier free access remains a major urban planning failure.

Part of the original planning of roadways near the MUHC called for blocking Upper Lachine Road in such a way that a four-turn labyrinth would have been necessary to negotiate in order to circumvent it. This is a main route into the Saint-Raymond district of NDG. Blockage would have had disastrous effects. It was argued by hospital planners that this was required for the efficient flow of vehicles to the MUHC from a nearby expressway. The St-Raymond community realized that the resulting traffic arrangement essentially would isolate their community for the sake of suburban car traffic. They vociferously fought back at every meeting and it appears that this intended blocking of Upper Lachine Road will not happen. But they must remain vigilant against being disregarded by a suburban view of development.

But the residential districts to the north of the railroad lines are isolated from the MUHC. Their segregation arises from the lack of a viable connection by way of the Vendôme intermodal hub as outlined above in the 1st point. Again, an insistence on vehicular access over all others has led to isolation of communities from the MUHC Glen.

3- The MUHC Glen does not capture any ambient energy. It is entirely reliant on exterior sources.

Large mega-projects have the rare opportunity to capture a substantial part of their energy needs from their immediate environment. Since the MUHC is an essential institution for Quebec society, this kind of energy capture would give the MUHC a measure of security. And the economics of significantly lowering energy expenditures should be encouraged.

It is important to view this aspect in a global perspective. The European Union in 2010 passed a directive that requires each member state to develop plans to achieve near net-zero energy for all new public buildings by 2018. It defines this type of building as having a very high-energy performance with an on-site or nearby renewable energy supply that covers a significant portion of its energy needs. In western Canada there are an increasing number of projects which are actually net-zero, producing as much energy as they use.

The MUHC Glen is targeting LEED Silver certification. All that this indicates is acceptable architectural practise as regards the environment and energy. Gold certification is most often interpreted as being exemplary and Platinum as leading edge. In this regards Manitoba Hydro Place in Winnipeg is well ahead of the MUHC. There the design team made a whole series of decisions that led it to become the most energy efficient office tower in North America. It has received LEED Platinum certification. That building has a geo-thermal Heating/Air Conditioning system. Together with other design elements this allows a 70% energy savings over a typical office tower.

Even China is making significant forays into on-site capture of energy. The Pearl River Tower in Guangzhou employs a Photovoltaic system integrated into the building’s external skin and Vertical Axis Wind Turbines designed to use the geometry of the building itself. It is the most energy efficient tall building in the world and is an example of China’s goal to reduce the intensity of its carbon dioxide emissions.

The MUHC Glen is well situated to have employed some of the techniques mentioned. Since the structures of the complex are not in the shadow of any building or geological feature, Photovoltaic Solar Arrays could have been incorporated. And with all the excavation for underground parking, certainly there is little reason that geo-thermal Heating/Air Conditioning system could not have been considered.

As there are no obstructions to the west from where prevailing winds arrive, the MUHC might also have employed Vertical Wind Turbines to harvest that wind. And because its grand concourse organizes the series of pavilions strung along it, these westerly winds could be led through the gaps between pavilions. There the Venturi effect would have increased wind speeds to harvestable levels by Vertical Wind Turbines even if the open-field wind speed was low.

This absence of any such innovation in the building of the MUHC is another demonstration of missing the connection to 21st century Urban Enlightenment.

4- The parkland encompassed within the great arc is given over to vehicles rather than to visitors, patients, and staff.

From the outset, the field between Decarie Boulevard running north-south past the complex and the great arc of the MUHC concourse was foreseen as a park. It was to humanize the mega-complex amidst the overpowering mass of buildings. It would open the door to the beneficial effects of Nature. But in the MUHC’s final form that purpose has been contradicted.

Along the grand arc runs a vehicular road. Adjoined to it is a parking lot at the midpoint of the arc. In front of the Children’s and Shriners’ pavilions is a large spiralling car ramp to underground parking. At the other end of the park are an exit ramp and a return road. The sum of this vehicular infrastructure reduces the park by 35 % and makes it but a backdrop to vehicles.

It is as if this mega project could not retreat from advertising its suburban choice of car dependency. This park could have been saved. The designers could have had all traffic ramp underground immediately upon entering from Decarie Boulevard, leaving the great arc free to engage with its park without the physical and psychological barriers of roadways, continuous traffic, and parking. The drop-offs for the different pavilions could then have been underground, protected from inclement weather. There would have been no need for loss of park to ramps and access roads. The playground for the Children’s hospital could then have found a home in front of its hospital.

The domination of outmoded 20th century design thinking has ruined the chance for a wonderful park and lost all the potential beneficial effects for the MUHC Glen community.

Dysfunctional Process

The mechanisms that were supposed to alter design deficiencies utterly floundered. The failures of not incorporating all public transit adjoining the site and of not connecting this mega-health complex to existing surrounding urban neighborhoods are extremely serious. They are of a level of failure that should have called a complete halt to construction so solutions could have been found. Where were the redesign sessions?

In retrospect, there are three main reasons why the MUHC Glen campus failed in terms of urban planning:

A- The Quebec government is far removed from understanding the precepts of Urban Enlightenment. Thus, it is unable to set such a framework within which an urban megaproject could proceed. Recent evidence of this weakness was its failure to comprehend excellent briefs submitted to the BAPE (the provincial office of environmental hearings) on the rebuilding of the Turcot interchange. Those submissions came from all segments of Montreal society, including its political class. They had no effect. The Turcot, to the south and below the MUHC, was a lost opportunity to move to a new conception of the city and to abandon once and for all that impoverished dream of the 20th century: the suburban treatment of urban development. But such suburban poverty of planning is exactly what the MUHC represents.

B- The decision by the Quebec government to place the MUHC complex into the hands of a Public Private Partnership contract tied down the project to the initial conditions set out to the bidders. Once awarded the project, the SNC-Lavalin consortium went full speed ahead with design and build. All constructive criticism was handled by their public relations wing. Its profit-based rationale and immunity to any criticism that might lead to redesign caused major failings. It is now obvious that PPP contractual arrangements are only suitable to simple well-defined situations, not those of a complexity calling upon sophisticated design and redesign.

C- The major stakeholders who fall under the umbrella of the MUHC Glen were not coordinated into a holistic whole. They are the Ville de Montréal, the Societé de Transport de Montréal, the Agence Métropolitain de Transport, le Ministère des Transports du Québec, and Canadian Pacific Railways. They each have their own range of expertise and jurisdictional territory to defend. The MUHC called upon them as required during different stages of construction. What was lacking was a special over-riding body that could have orchestrated the stakeholders into a holistic solution. The isolation of the project and its disregard of the intermodal hub of the Vendôme station would never have occurred if such a body had existed.

Local voices of influence in Montreal did not speak up when the serious failings of this mega project became apparent.

These failings will have serious consequences for many communities in Greater Montreal. Unfortunately, urban leaders did not sense, or believe, that they could change the direction of a mega project which had been set in motion to outmoded principles of 20th century urban development. Suburban degradation won, and a golden 21st century opportunity was lost.