Land for Fatimah by Veena Gokhale, Guernica Editions (Canada), 2018

Veena Gokhale’s second book but first novel is a bridge spanning cultures and languages across South Asia, Africa and Canada. It is about the separation of vulnerable populations from their ancestral land through bureaucratic systems set up to work against Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs). The ubiquitous forms, documents and multifarious “schemes” add a legal veneer over the rights of those who belong “to their land, not the other way around,” and for whom the buying or selling of land is an incomprehensible “abstraction.”

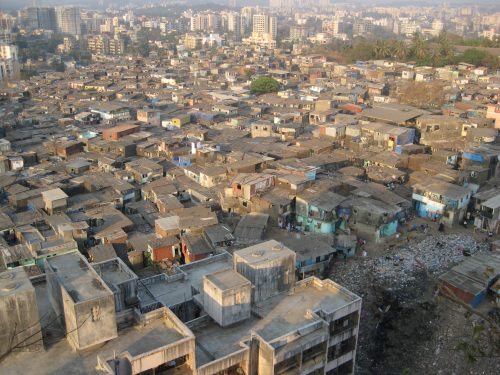

Regardless of whether it is a small slum in Andheri (Bombay) or Fatimah’s village of Ferun – the Aanke people’s family farmland in the fictional country of Kamorga (Africa) – the decisions made by Bombay’s district municipality or Kamorga’s central government are irrevocable. Shanty huts are bulldozed to build colonies, and ancestral land is taken over for cocoa production. Promises for compensation are made and broken as a matter of course. Hopes are built and shattered, filling generations with powerlessness: “When land is abundant . . . communal rights can exist more easily. But as it becomes more scarce, individual rights advance.”

And flowing stealthily beneath is the deep animosity of the Kakwa against the minority Aanke people displaced from their land into the settlement of Madafi. Originally from West Africa, the Aanke do not belong, not in Kamorga, one of the many countries “collapsed into AFRICA.” Among all Kamorgans, there is an unspoken code: “support your own people against a foreigner.”

Working to relieve some of the stress within this environment are well-intentioned multinational non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as HELP (Health, Education and Livelihood Skills Partnership). These organizations are tightly bound by complex protocols that clearly identify the “regulars” with identity cards who can be served, and the “irregulars” who are supposed to be turned away. Although exceptions are made for IDPs, HELP offices in Toronto and Kamorga can never agree upon recognizing the Aanke people as IDPs since they are believed to have received compensation for their land. HELP staff therefore do their best to serve the “irregulars” who show up “the day after and the day after . . . lining up on the verandah, spilling up into the sun-roasted compound, waiting patiently for hours and days on end.”

The list of names at the beginning of the book helps the reader in keeping track of the slew of characters. To name a few: Anjali Bhave Bhagat, acting Executive Director of HELP’s African regional office, who provides a central perspective to the novel; hard-working Mary Iwu (Anjali’s maid) and her son, Gabriel; Elizabeth, Anjali’s loyal assistant; Fatimah Ditta and her immediate and extended family of Aanke farmers; Grace Madaki, the iron-fisted chairperson of HELP; and Hassan, the charming and unforgettable contractor hired by HELP. The fictional language they speak is Morga, Kamorga’s national language.

Whereas on the one hand, Land for Fatimah is about the poor and the dispossessed, it is also about the plight of foreign or local NGOs: “Community Based Organizations, Charities – linked to religious groups or otherwise, organizations spun from trusts, organizations linked to universities and other institutions” that do not amount to more than “drops in an ocean of need.” Forced to categorize people, they end up helping some while ignoring others. Although a few of these organizations become corrupt, “some wrong-headed, others merely inefficient,” almost all of them are “well intentioned.” In actual terms, there is not much that they can change, but it is difficult to imagine life without them.

Land of Fatimah provides a rare insight into the day-to-day challenges faced by these organizations. Set against the backdrop of busy city streets with swarming Matatas (privately-owned mini-vans) and the all-consuming dust of African countryside, this novel makes a great read.