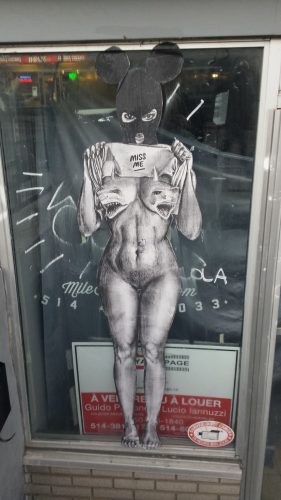

Mural by feminist guerrilla artist, MissMe, on Park Avenue in Montréal https://www.facebook.com/missmeart (Photo by Jody Freeman)

Nelly Arcand, Breakneck, Anvil Press, 2015, 223 pages. Translation by Jacob Homel

Nelly Arcand was a shooting star in Québec’s literary scene. Between her first novel Putain in 2001 (Whore, 2004) and her fourth and last novel Paradis, clef en main in 2009 (Exit, 2009), less than a decade elapsed. Her third novel, À ciel ouvert, published in 2007 (Breakneck, 2015), is a vivid and troubling account of lives lost in the maze of contemporary Western culture, where women’s bodies are literally torn apart and reshaped to meet impossible standards of beauty designed by men for men.

Through the prism of a loveless love triangle between Julie O’Brien, a bright documentary screenwriter, Rose Dubois, a proficient fashion stylist, and Charles Nadeau, an up-and-coming studio photographer, Arcand focuses a harsh light on the self-destructive lifestyle of trendy young urban professionals living it up on Montreal’s Plateau Mont-Royal.

It is no coincidence that the action starts – and ends – on the high-perched, sun-drenched terrace of a loft apartment building on Coloniale Street. Set in an age “where success shouts from every rooftop,” the novel hints at the collapse of a “world that was bursting into flames all across the planet,” by exposing the collision between three lost souls.

Lives already dead

Left heartbroken by a short-lived relationship and “tormented by the climate and temperatures that were no longer just conversation, but daily experience, worrisome in the long term because behind them hid a surge and a charge towards destruction,” Julie is going through life like one of the walking dead: working out to keep her body in shape, while destroying her soul with alcohol and drugs. Soulless and numb, “her existence was no more than armour against life, against the world and all it contained.”

Rose – “a true beauty, but in a commercial, industrial way” – lives as one woman too many in a man’s world. Conscious that her work as a stylist consists “in the sculpting of others, participating in her own disappearance,” she in turn has her own body sculpted by plastic surgery, “torn asunder by medical technique and its ability to recast.” Living as “Charles’ excrescence, the shadow of his eye, the slave who organized, brightened and showcased other women’s beauty before exiting the frame, where no one could see her,” Rose is a woman without an existence of her own.

As for Charles, he appears to be an average man who, exposed to and attracted by so many pretty young women, “had slowly developed resistance to his own tastes.” Behind this facade he hides “a few defects in his soul,” inherited from his father: a schizophrenic butcher who raised his son with misogynous paranoid theories about “murderous and mutant female assassins” and about “the treachery of women.” This childhood trauma left Charles, the butcher’s boy, with a fetish perversion for sadomasochist gore pornography, a secret sickness that Rose, in her self-abnegation, came to accept without questioning.

The eye of the storm

It is on the cursed roof of the building where she just moved in with Charles that Rose finds herself involuntarily pushing Julie, who happens to be the couple’s next door neighbour, onto Charles’ path. During this meeting that seals their fates – and Charles’ – in inevitable doom, an act of God testifies to the irreconcilable enmity between both women: lightning striking the guardrail of the terrace where Julie and Rose are standing. It is as if the tragic events set in motion on that summer day were commanded by “the power of mighty nature throwing back mankind’s arrogance in its face.”

Rose’s mistake inevitably brings Julie and Charles together, and pushes Rose herself out of the life of the man she had devoted herself to and into the arms of the plastic surgeon who had been moulding her for Charles. While Julie attempts to cure Charles of his sickness by indulging him in his vicious perversions, Rose intends to sacrifice what’s left of her body in a desperate attempt to get Charles back.

With the reluctant help of her surgeon, Rose has her most intimate flesh carved and sculpted to become the very image of the ideal women Charles had spent his life fantasizing about. Using her body as a weapon – butchered by another man – Rose “was plotting to win Charles back, or just destroy him,” whichever way it turned out.

When images are cages

As the story develops, Rose and Charles become the subject of Julie’s next documentary project where she wants to talk “about images as cages, in a world where women, more and more naked, more and more photographed, covered themselves in lies.” This project looking at “the aesthetic obsession that Julie had long considered a Western burqa” echoes directly the author’s own thoughts on what she called a Burqa of Skin (the title of Arcand’s posthumously issued collection of cultural critiques): “It was a veil both transparent and dishonest that denied the physical truth it claimed it was revealing, in the place of real skin it inserted skin without faults, hermetic, inalterable, a cage.”

This is where, behind the third person narration of the novel, we find glimpses of the auto-fictional nature of the work. As it is, the underlying themes of the novel – manufactured beauty and death – are the same ones that seem to have obsessed the author throughout her brilliant but short career, which ended abruptly when she committed suicide on September 24, 2009, a few weeks before her last novel was published. Whether or not it’s the writer’s own suicide that is foreshadowed in the book is left for the reader to ponder.

What is clear however is that the book depicts a very real world – Arcand’s world which is, whether we like it or not, also ours. Breakneck is the unbearable story of a world where patriarchy’s rule continues to oppress women, forcing them to disappear altogether inside themselves, and where a lost sense of beauty leaves only a trail of death, suffering and solitude.