Editorial note: Charles William Johnson shares some of his intriguing and controversial research into ancient art forms, with special reference to the legend of Pan Gu as it appears in both Chinese and Maya cultures. He describes how transparencies of the many stone images, when overlaid on one another, depict an ancient form of animation that he calls “paleoanimation.” We are still trying to wrap our heads around some of his findings.

Dedicated to Maurice Cotterell

Encoded Images

Various ancient cultures encoded images into their artwork. The ancient Maya encoded images relating to other cultures in their artwork. Some stone bas-relief sculptures of the Maya offer visual keys to decoding the hidden images. Numerous methods were used to achieve this. In fact, there are almost as many methods as there are sculptures. In this study, only one image is presented as an example of the encoding procedure, which is scientific in nature as it involves concepts of math, geometry and motion in terms of reflexive and translation symmetry.

Generally one does not expect to find any encoded images in ancient artwork. Even the idea is looked down upon by institutional archaeology, not a strong field of research. But researchers who consider such a possibility might search for themes related to the culture being studied and to that culture’s own mythology.

In fact, the first encoded image that I stumbled upon in October 1992 was that of a hummingbird, Huitzilipochtli, an Aztec deity of love and war. The hummingbird appears encoded in a composite fourfold view of the Aztec calendar. Finding the hummingbird seemed logical enough, as it pertained to Aztec mythology. Other scholars such as Maurice Cotterell* were finding similar mythological images in the Maya culture.

After uncovering the hummingbird in the Aztec calendar, I began to study the math and geometry in ancient artwork, searching for other possible encoded images. I reasoned that if there was one image, there must be others. For almost three decades now, I have been documenting innumerable encoded images in ancient art from around the world in my research project: Earth/matriX, Science in Ancient Artwork.

To date, unimaginable encoded images have been discerned in the ancient artwork of eight different cultures. One of these is the image of Pan Gu, the Creator of the Universe, a mythological being of Chinese origin, which appears encoded in a Maya sculpture.

Seibal, Guatemala, Stela 13, 870 A.D.

Pan Gu, the Creator of the Universe, was said to be the son of Yin and Yang. His image is often depicted standing or sitting with the yin-yang symbol in each hand. The Pan Gu creation myth is presented in different versions, but it may belong to a period of a thousand years before our era. The name is written in varying ways: Pangu, Pan Gu, P’an Gu, Pan-Ku, etc. Mirror the image in a certain way and there appears Pan Gu with a dog face, the Creator of the Universe.

The Mirror Image

Pan Gu, Creator of the Universe

To find an ancient rendering of the image of Pan Gu through visual reflexive symmetry is significant in itself, given that there are so few ancient depictions in existence. But to uncover this image encoded in ancient Maya art challenges all realms of human knowledge to date. The Maya image of a standing figure dressed in serpents (in which the Pan Gu image is encoded) requires its own space and interpretation with its own cultural significance. For now, our comments are restricted to the Pan Gu image that appears therein.

Different versions of the Pan Gu legend say that he had a dog face and carried a hammer and chisel (or axe) with which he created the Universe. At first nothing existed; then the cosmic serpent produced the cosmic egg, the primordial state that lasted 18,000 years. Out of this state, Pan Gu emerged from the egg and the yin-yang balance appeared. Pan Gu thus created the Earth, symbolized as Yin, and the sky, symbolized as Yang, keeping them separate by standing between them. This version runs from the Cosmic Egg to Yin-Yang.

Details of the different versions of the Pan Gu legend aside, the first question that came to my mind was how a figure of ancient Chinese origin came to be encoded in an ancient Maya sculpture. That’s a prerequisite query with no factual answer to be found in history books. Although many scholars have suggested, and still suggest today, that contact among ancient cultures was a reality, it appears that there is no definite physical proof. Similarities between some ancient cloud designs of Chinese bronzes and comparable designs in Maya sculptures have often been pointed out by scholars, but such prima facie comparisons of design always appear hypothetical.

Mirror image

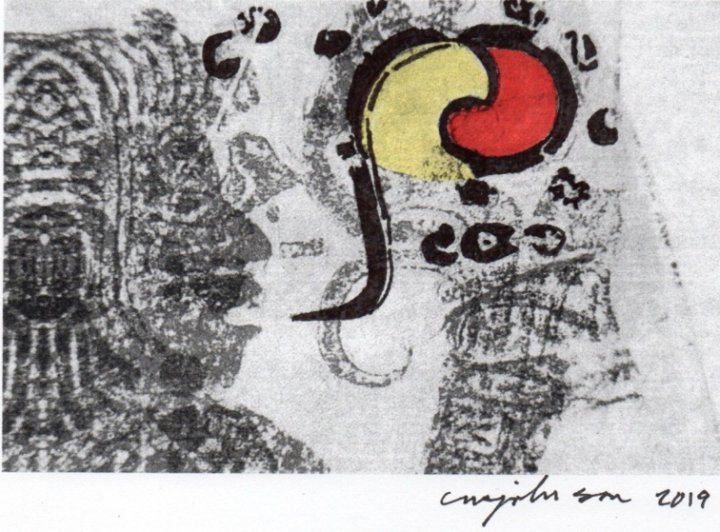

The image of Pan Gu presented here derives from mirroring one image of the Maya sculpture of Seibal with another, a left and right-handed view of the image. Maurice Cotterell has employed this method extensively in his work. The ancients used innumerable methods for encoding images in their artwork. I have employed and uncovered a few. In order to view the images, a certain degree of technology had to be developed, such as film transparencies now available through modern-day photography, and scanners and printers.

The film transparencies drawn from ancient designs are then overlaid on one another, and the search for recognizable designs can begin. It is next to impossible to merely look at an ancient image sculpted in stone and visualize a particular mirrored design. For example, look at the image that appears in Seibal shown here, and try to imagine the mirrored image of Pan Gu suggested by the design. Only by moving the two mirrored right and left-hand images overlaid on one another do the designs of the cosmic egg and the yin-yang symbol make their appearance in the hands of Pan Gu. This is shown in the paleoanimation “cells” (or images) below.

The possible contact among ancient cultures required for substantiating the fact that an ancient design from China appears in ancient Maya artwork appears to me to be confirmed in the ancient encoded images. When I first saw the composite image of a standing figure with a yin-yang symbol in each hand take shape in a Maya sculpture in Seibal, Honduras, I immediately wanted to know just how extensive was the practice of encoding images in ancient artwork, and if possible, find out what all the encoded images meant to the artists who created them.

For years, even though the composite images that I had derived appeared to have been placed there by conscious design, I kept thinking that perhaps they were random coincidences. The innumerable encoded images that I have derived to date are far greater in number than anything I had initially imagined. In addition, I recently found four different ancient historical figures in a single composite image, which shredded any idea of random coincidence. Confirmation of the idea of conscious design has taken 30 years.

The ancients employed an infinite number of methods to encode their images, from the basic mirror-reflection symmetry employed in this image of Pan Gu to much more complicated methods of translation symmetry, at times even involving the Maya glyphs appearing on some sculptures, with detailed geometries. It has taken me almost three decades to uncover a few of the methods. I suspect there are many more that will be discovered by searching additional pieces of artwork. In my research, I have pored over fewer than 200 ancient pieces of art. There are thousands in existence.

Once a specific method is detected for a particular art piece or design, this can open up an exponential number of images that may be accessed by anybody with a little imagination and lots of patience. At times I have studied an image in detail for days and weeks on end, derived a few images and laid them aside, only to return years later to find additional encoded images in that same ancient design. It is also a matter of perspective: I may look at a particular composite image for years and not see anything until I take a different visual perspective or focus, and suddenly the figure of a person may come into view. The degree of creativeness in the methods for encoding the images in ancient artwork is astounding, in my opinion. Many books could be written just on the methods of reflexive and translation symmetries employed by the ancients.

Seibal, Guatemala, Stela 13, 870 A.D.

The Dog-faced Pan Gu

Images in motion: paleoanimations

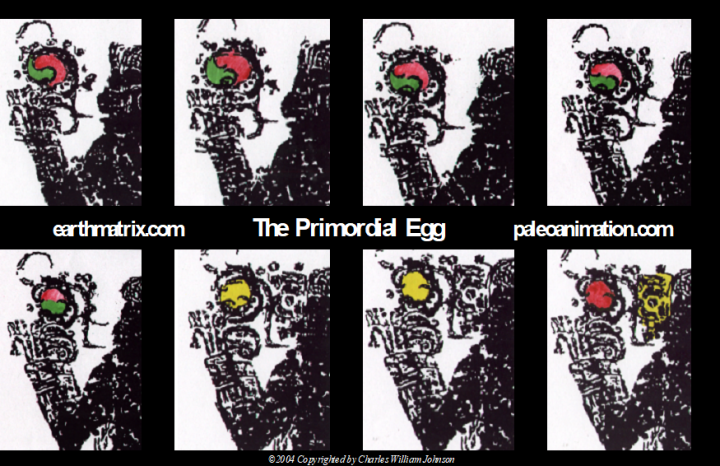

In the legend of Pan Gu, one version states that Pan Gu had a dog face. I mentioned the study of motion earlier. Aside from the encoded still images, such as the one of Pan Gu standing, it became clear to me that the distinctions between the apparent images and the encoded images were designed for creating ancient animations. I call these paleoanimations. By moving the film transparencies into different positions, one sees the cosmic egg turn into the yin-yang. And one also sees the dog face of Pan Gu make its appearance in other views. The concept of ancient animation encoded in the still views of the Seibal Maya figure becomes evident as one moves the right and left-hand overlays on top of one another.

As with the encoded still images, the ancients employed numerous methods for animating some of their images. The stop-motion methods could also be based on reflexive and/or translation symmetry, as well as other design methods (that are too numerous to detail here). Below are some of the possible motions of the Pan Gu figure from the Maya figure Stela 13, located in Seibal, Guatemala. This paleoanimation employs reflexive symmetry of a partial mirrored image type. The number of animations that one may create from a still image can be staggeringly high, with the movement between the two mirrored images occurring in micro clicks. The images shown here are from the single original design shown in the first view. With the mirrored detailed images, I then use stop-motion to produce the paleoanimation. Literally, one can produce an infinite number of cells derived from the single Maya image, for a more fluid sense of motion.

In viewing the encoded image from the point of view of motion, it then becomes possible to create ancient animation storylines, or paleoanimation storylines. I have found that the following thought holds true across various ancient cultures.

A popular adage is, “A picture is worth a thousand words.”

With the ancients, “A picture is worth a thousand pictures.”

The Chinese Creation Story of Pan Gu and the Cosmic Egg

An Ancient Maya Animation

Some versions differ from the myth of chaos (yin-yang) to the cosmic egg. Animated storyboards are designed, encoded in the original Maya image, which illustrate the relationship of the cosmic egg to the yin-yang in the legend of Pan Gu. With hammer and chisel, Pan Gu transformed the primordial chaos into cosmic order and created the Universe.

A single image may encode countless related images in an open-ended manner. One image that has been manipulated through math, geometry, motion and reflexive and/or translation symmetry can yield an infinite number of derived images. Further, a single image may encode different story lines for each of the different design elements in a sculpture. Here, I present a few cells of one example of the primordial egg as an example of many Earth/matriX paleoanimations derived to date. Different storylines exist, encoded within the Pan Gu image, but one may suffice to understand the idea behind ancient animation.

Also of note in the animated design is the appearance of the skeletal mask in the background, an element not referenced in the mythology, other than possibly as the “cackler” and the cosmic egg.

The Cackler and the Cosmic Egg

The transformation in the paleoanimation from the chaos of the yin-yang to the primordial cosmic egg suggests that with life comes death, represented in the skeletal mask. Variant interpretations may exist, no doubt. What may have been the original meaning of the design in symbolism remains a mystery. As with all graphic symbolism, interpretations remain with the viewer, unless specified in the historical record, of course.

Observations

One of the main lessons that I have learned from studying the encoded and animated designs in ancient artwork from around the world concerns the methods for encoding images in the ancient artwork.

Popular cartoons and comics utilize different cells or images to create a storyboard. The ancients designed a single cell for the viewer to derive an infinite number of cells, visuals that may produce an animated storyboard.

The ancient animations were designed into the original artwork. The storyboard presented here, illustrating the relationship of the yin-yang to the cosmic egg, is not something of my own creation. I am simply following the instructions as I have understood them that are encoded in the original, ancient sculpture. My participation is limited to conveying the message I interpret that was encoded by the original Maya artist, who had in turn rendered the story from the mythology of ancient China.

Now, as I contemplate the hundreds of encoded images and storyboards that I have uncovered in artwork from various ancient cultures, I continue to wonder and marvel at how the information was communicated from one culture to another. The encoded images where ancient cultures register images from the mythology of other ancient cultures undoubtedly confirm contact among these cultures.

With regard to the Pan Gu image, the story is not complete. There are many other encoded images and storyboards told within this single image. As I mentioned, a single image encodes countless story lines. The encoded images reflect a conscious purpose of communication with the generations that were to follow them. For example, rather than being openly etched in wood for their contemporary viewing, they were encoded in stone, unnoticeable at the time of their rendering and noticeable only now, centuries later. Perhaps the ancients encoded images in their artwork for all of us to see – all of us who have followed them in time.

*For a complete list of the works of Maurice Cotterell, visit www.mauricecotterell.com

In particular, see: The Mayan Prophecies, 1995; The Supergods, 1997; Future Science: Forbidden Science of the 21st Century (2012).

Further suggested reading:

Earth/matrix: Science in Ancient Artwork, http://www.earthmatrix.com/main_themes.html

A drawing by Shanti Kumari, inspired by the image of Pan Gu

“China’s Pan Gu and the Cosmic Egg Encoded in Ancient Maya Art”©2019-2020 Copyrighted by Charles William Johnson