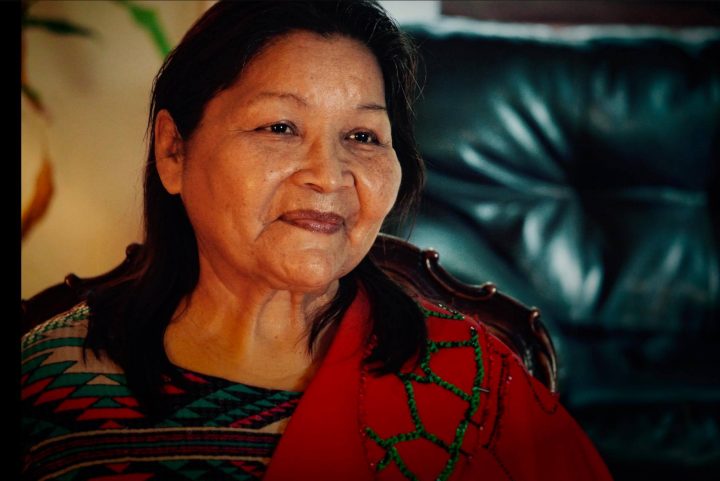

Introduction: Shanti Kumari first took a course on the history of Native Americans in Canada at Dawson College in Montréal, but her interest in the First Nations has its roots in her native Mexico. Shanti is a Mexchica ceremonial dancer / singer. She recently had the immense honour of meeting Ms. Helen Cote Quewezance from the Cote First Nations Reserve in Saskatchewan, one of the bands in the Treaty 4 area, during an Ojibwe language course given by Ms. Cote Quewezance at the St. Kateri Center in Chicago, Illinois. What follows is her interview with Ms. Cote Quewezance.

SK: Tell us about yourself and where you’re from, please.

HCQ: This is how the State and the Church brainwashed us as little children. They wanted to assimilate, enculturate and colonize us.

My real identity is and my traditional spiritual name is Ninzo Mikana Ikwe Ka Pimoset (Woman Who Walks Two Roads). In 1955, at age 6, I had to go to residential school. So the Indian agent, the priest and my parents took me to the band office and registered me with an English name. I was registered with the Government of Canada (a birth certificate). I was called Helen Cote on my birth certificate.

When in residential school, the Catholic Church St. Phillip’s Indian residential school changed my name again to Sylvia Helen Severight (my parents were not married yet). My parents married in the 60s; after that I was Sylvia Helen Cote. I married in the 1970s and my name changed to Helen Quewezance – apparently Sylvia was not on my birth certificate and was not my name at all. I chose to put Cote back in my colonized name: Helen Cote Quewezance.

The Government of Canada, the State and the Church changed residential school Native children’s names as often as they liked so we would never know what our real identities were. The purpose I believe was to brainwash us and to confuse us. In residential school I was given a number to further humiliate me. I believe the purpose was to assimilate the children. I did forget who I was and believed Helen to be my real identity. Helen has no meaning, it is just blank, but my real name and identity has a purpose. My dad told me who I was, and I am glad he told me.

I am Saulteaux/Ojibwa (People of the Rapids) which are the names given to us by the newcomers.[1]

Our original tribal name is Nekawa: Good Speaking People, Fundamentally the Good People.

Originally the Algonquian people migrated from the East and the Great Lakes centuries ago as one of the twelve Algonquin Families which include the Salteaux / Ojibwe, Chippewa, Cree, Cheyenne and more.

SK: What place do women hold within your clan, tribe or tradition?

HCQ: First of all, the Nekawa people were socially, culturally and politically matriarchal. One of the sayings is: “Grandma made the rules, the laws, and Grandpa enforces them.”

Since the making of the Peace Treaties, Sacred Treaties were made in the presence of God and as such those treaties can never be broken. The Native people are the only people in the world to have “The Great Law of Peace.” We do not settle disputes with war. Treaty men have been making deals with immigrants. The immigrant men assume that the Native men make all the decisions and laws. Which is not true. The women have a council and they chose their leaders. Only the kindest, bravest and medicine people were chosen to be leaders. It did not matter if you were a woman or a man. There were many women warriors and medicine women. The women watched carefully who would become leaders.

Women sanctioned and chose the leaders and the women headed and kept sacred lodges. IKEW (a woman) owned half of some ceremonies. She owned the home and the soil of the lands. If these were not sanctioned by the women councils, it was not legal. For example, the home and the lands are owned by the women. In fact, lands were never given away or loaned out to immigrants by the leaders of this land.

The newcomers did not know Turtle Island laws. Immigrant men talked to chiefs and warriors and basely talked to men, believing they are the leaders. Far from it, the Nekawa people have a well-structured social, cultural and political system which existed for centuries. The tribe did not have elected chiefs and councillors, they had headmen and a traditional chief. Headmen and chiefs were not voted in (we did not have the vote). The clan mothers from each Algonquin family chose a leader. Clan mothers would not sell their children’s food.

Usually the newcomers, government officials or premiers of Canada will seek out the men to consult before breaking the forest or digging mines. They will say it is their duty to consult, so they seek out the men, the chiefs. In our language we used to call a true traditional chief Ohkemancan, a chief who follows the laws of his people, a sovereign and self-determined chief. The chiefs of today we call Ohkemanca-nuk – a false chief who follows the laws of another race of people, not sovereign and not self-determined. In fact, many times the local people are warned “not to talk politics in meetings or gatherings.”

In times past, the white man did not seek out Native women to consult with about important matters like buying land. If European men at that time treated their own women like property, like cows, why in hell would they come talk to Native women? In those times, even today, Native women are not respected. European men make Natives their servants. When the Spanish first came to our lands, the pope told them to invade the lands and take all their gold. After all, he said, they are not real people; they just look like us; they have no souls, and God says Christianize them or kill them. In fact, Canada still believes that Doctrine of Discovery. Court cases are won based on that doctrine.

We have a council of elderly women, spiritual ladies who have children, grandchildren and young girls as well. Native men support these councils.

When you move into the age group of 50, 60, 70 years old, it is a rite of passage into a Kici Anisnabek (elder per se). You become everyone’s teacher. You help everybody. You are the communities’ Grandmother and teacher of young men and women.

All young men and women are in training to become the new leaders and the keepers of lodges. One saying was “Young men, if you never learn anything from the women in your family, you know nothing.”

The role of a woman has nothing to do with being a wife or a mother but: who are you? Know who you are.

We don’t have that European “thing” where you are 18 years old, you leave home and you never have contact with your old people or your community. Then when you are old, sick and dying, you wonder why your children are not there for you.

My job is to teach my people what they have. Their identity. Who they are and what they are. I teach them the meaning of Ojibwa: fundamentally good people, couldn’t be bad if they tried. I take my job seriously. I teach the language and the values, the laws that are tied to that teaching.

We’re born with gifts. Everybody, little kids are wiser than a mature person, or even a bishop. I was taught to respect other religions. I might refer to religion to make a concept clear. I know the Catholic sermons and prayers. I was in a residential school for ten years, but I don’t criticize it. We sued the church for physical and sexual abuse. It is never completed. We have claims against the government for taking our children away.

SK: It is still happening today, right?

HCQ: Yes, the stealing of our children is still happening but under a different name. The same practices continue and the same cruel practices.

SK: The Prime Minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, conveyed a message to the Pope and Church to ask for pardon for what they have done to the First Nations. Has that helped in any way?

HCQ: They say they’re sorry it happened. But our definition of an apology is different. Long ago, if you kill somebody, you go right up to the victim, right up to our face, right here, and go through a ceremony and give us gifts or whatever you are potentially able to give. If you can give a jacket, you give a jacket. If you can give financial help, you give financial help. If you can give programs and social services, then you would give that. An apology is nothing without the destruction of those cruel institutions that have tried to destroy our Native race. Knock down and label past Prime Ministers that have paid for the killing of Indians and their children.

For example, if you killed a son, then you give wood and water to the parents, whatever the son would have done. It is a lifelong obligation. But the Catholic Church does not scream over the ocean: “I’M SORRY.”

That is not good for us. Sorry does not mean anything to us in our language. There is no word for sorry in our language. When children are stolen, I look at it in this way: My children were taken away from me. The presiding judge said after I begged him to please don’t take my children away from me, he looked at me with contempt in his face and said, “You come from a family of criminals and you will never amount to anything.” I cried and begged some more. He slammed his hammer down and took my children away forever. My world was shattered, my mind shattered and I lost my sanity. I had a nervous breakdown. My babies were gone.

I know the newcomers, the immigrants of my land, think we are stupid people. In defense of the laws and behaviours of mainstream society, the immigrants say, “I never took your children away; it wasn’t me so why should I apologize?” Well I say society people could have said “Give those children back – it’s not right to take a child from its mother’s arms.” It’s against God’s laws – only barbaric people would steal children and abuse and kill them. Society did not do an outcry. The immigrants joined right in and took in foster children, adopted our children and changed their names. I say an apology is not worth anything. Stop taking our children now, let us work out how to decolonize ourselves and at the same decolonize yourselves. You’re a messed-up society.

SK: If you would like to include something written by you as part of this interview, it would be nice. You write, don’t you?

HCQ: Yes, I write stories and I would like to publish my short stories and publish my MA [Master’s thesis]. Even though my tradition is oral. If you don’t know Native people’s demise orally and then try to help us, you can’t until you practice it… if you listen here in your ears and put it here in your heart and then live it the right way with kindness.

HCQ: My son was adopted out. They told him I was an alcoholic, a drunk. I think he believed them. But now in his 40s with a family and children, he wanted to find me. He found me one year ago, through Facebook. He didn’t know my name. He found my other son.

I wrote a thesis about this for my Master’s at the University of Saskatchewan. The title is “Damaged Children and Broken Spirits.” You can find it if you Google my name, Helen Cote, and the title of my thesis.

I lost four children. Two came back when they were 10 and 12, the other at 17 and then Darren at 41. I thought he died because he never found me. He wants me to meet his adopted parents, but I said I didn’t want to because if I did I could slap her, that is how I feel. But I won’t do that because of him. He is my son. I respect him.

Canadians – immigrants – should know you don’t take a mother’s children just because they’re not like you or because you think they’re poor. You don’t use an army to push those evil kinds of values. You just don’t do that. Like the RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police), to be precise. The priest came with the RCMP to help them remove children. Child welfare agencies still use the RCMP and city police to remove children from their homes.

My son was born in Winnipeg, and they took him from the hospital as a newborn. I dedicated my thesis, “Damaged Children and Broken Spirits,” to him, Desmond Cote, and to my other children. He changed his name. It is now Darren James.

SK: Regarding traditional cultures and the environment, what direction is our Grandmother Earth and her Aboriginal peoples and traditions taking?

HCQ: Well I can speak just on my own life. I went to university to learn about these abusers, the State and the Catholic Church. My Dad told me to study both sides: my culture and the new peoples’ culture. You can’t just jump into fixing the environment. You must know who you are. My professor said, “You’re going to be an expert,” and I said, “How can I be an expert if I don’t know who I am?” So I asked my medicine man dad who I am. He told me my name, my purpose in life, and my strengths.

I am a teacher of my people. I am a Clan Mother and I am a traditional leader. Doing my thesis, studying our children and then those who kill and beat their own children. Even I wanted to understand where that comes from, and at the same time, I am learning through my dad and my professor. Now I know who I am!

Then I thought I should help Mother Earth, so I went on to get my PhD. And along comes Mother Earth and all her wild dog packs, moose and elk who are sick with chronic wasting disease. The animals have treaty rights. I am fighting for their treaty rights, too.

SK: I have more questions. Is it okay? Do you have more time?

HCQ: I don’t mind. I like passing the message on. When I tell people a story, it is your responsibility, your duty to pass it on like smoke signals. It is going, it is going, and it goes a long way. You don’t need an official paper letting you pass it on. You have it from high up: a Clan Mother. (Ms. Quewezance smiles.)

SK: What would you like to share with people regarding the Plant Kingdom, its importance and any changes therein?

HCQ: First, the plants are known as people; they have a culture and values of their own. They are smarter than us and can teach us many things. Plant people could protect us. Plants are not meant to be bought and sold. The way I do it, I like to choose one plant at a time. First, I learn about the trees: fir, spruce, Douglas, and tamarack trees. The other trees that are imported from other countries are no use to me.

I teach my children and grandchildren and other people who want to learn. I put out tobacco first and honour the tree. We believe the trees are our grandfathers. Science has backed us out on that one, we have the same DNA as a tree and the trees are good parents. We look. We learn together. We find a spruce tree, I pick spruce gum, some spruce gum is shaped like marbles, some tear-shaped. It is fun. When I am picking spruce gum, I know it is strong medicine. I will do one thing only. I do not pick a bunch of different kinds of medicine. I pick only what I need.

If it is sage I want, then it is only sage I will pick that day. Now the young people come with many jars. It’s already picked and dried, sitting inside jars, grounded already. I don’t know how you can learn that way.

Like the Labrador tea by fir trees or moss on ground. They don’t have too much places to grow. They are considered weeds. They’re food for animals. Labrador tea is medicine and helps us with colds.

When animals get sick, they go to the bush. They lay down and eat the different types of grass. It is good to watch the animals, what grass are they eating when they get sick. They heal themselves and then go home. Animals were our teachers. Now we don’t have them. Too much crops. Too much pesticides.

They say organic is expensive. Well, “TOO BAD,” I say. They can’t filter out chemicals. We need sloughs, not ponds, but clean, wild sloughs. But people are dumping in these. They should be cleaned for wild life and plants. We need to help the plant life.

I am trying to teach my people that animals and Mother Earth have treaty rights and should also be protected by Canadian Laws because they are living breathing lives. We’re related to them. They are our brothers and sisters. They always say, “Out of sight, out of mind.” I don’t think you should think that way.

We all like to go to the bush. We all feel refreshed, and massaged. You need water for everything. We are the magic people and we can communicate with plants and water.

Mainstream should work with Native Peoples for water and everything. Stop saying, “I didn’t do that, why should I have to pay?” Lame excuses. We are all involved. I used to say, “Somebody ought to do something, not me.” Now I take risks.

Like those people taking our kids saying, “I didn’t do it, they gave them to me.” You’re lucky we gave you some land to rent while they didn’t want you in your country. Aboriginal people don’t ask for much. They just want to get along with you.

What I am trying to do right now is environmental law. I write for grants for wild dogs. Indian Affairs is not recognizing that animals have rights. You can do anything to them, to the land. It’s just a piece of land. I’ll just buy it and sell it. No emotional value. Just crops to sell. No responsibility to the land; after all, land is free and stolen. And how could you respect it, it’s not your land. No endearment for the land. That is the biggest hurdle I must go through.

If you have problems with animals, well, kill them. If you have problems with cancerous cells, well, kill them. That is not the Indigenous way. No relationship.

You come here and become a citizen. That is not good enough here. It can be a paradise again. You cannot just come here and live like you did in your country. You need to adapt to the ways of the Indigenous people here on Turtle Island.

I must try and change the attitudes of the immigrant people, the newcomers. Universities should have Indigenous cultures as a discipline all by itself. It is starting to be that way. Before it was as an inter-disciplinary, here and there.

The hiring committees must change. You must have Kici Anisnabek (elders) in every committee. Just because they don’t write anything down doesn’t mean they’re uneducated.

Attitudes must change.

Structures must change.

With us, with plants, the lily comes from the stars. The lily can come and visit you any time. One day we woke up and there was a lily outside our door growing. It is hard to grow a lily, but they might come. Birch tree chaga grows on a tree that is going to die. At its death, it’s giving strong medicine to the people. We’ve been using those plants for a long time. We know them like people.

Some cures take a day. We don’t believe in miracle cures. We believe it takes respect and patience. We call it a way of life. People like learning about that life. But I don’t know why they don’t follow it.

Plants need water. They like music. They like talking, like corn cries when you hurt it. You can’t be mean to them.

But they need a place to grow. You have flowers; they need freedom, with plants growing around them. Weeds give food to a flower to let it grow large. But weeds get plucked.

SK: Is the Ojibwe language being remembered?

HCQ: First, the Algonquin people were the biggest tribe in North Americas. It consists of 12 families and [their language] should become the language of the country. Like in Canada, English and French are not the founding languages. Aboriginal languages are above them. Everyone should learn to speak them. In my culture, people knew one sign language for all of them. But they knew many languages to trade from top to bottom of the world. They had the command words.

Not uncommon for Indigenous people to speak three languages. The language is very picturesque. One word can explain everything.

With one word you can see them all, the seed growers, transplanting, all the flowers – you can see them all in one word.

Ojibwe ought to be preserved. You can see the whole life situation of the flower by one word. Like the poppies that were born there, who put them there? Like the lily in my yard that appeared. They were born there and suddenly, they left. You must respect that it is visiting you.

Language is so important. We still speak our language. You cannot learn the Ojibwe way of life if you do not know the language.

SK: Is there any good thing that has come out of the residential school system?

HCQ: You mean “residential schools, slash, prisons.” It was not just a school, it was a prison. The [good] thing that came out of there is a determination to hang on to my culture and my language. My parents told me – my mom and dad and my grandfather and grandmother told me, “Never forget who you are.” So I hung on to those things. And my parents also showed me how to talk to God in my hardest times. So a lot of good things came out of that, out of my teachings.

SK: Are the schools still open?

HCQ: They’re closed now, but the buildings are up yet.

SK: Can you tell us about the eastern migration of the Ojibwe people?

HCQ: I can tell you about the Seven [Fires] Prophecies of the Ojibwe. Long ago, centuries ago, we used to live on the East coast up to the Great Lakes, Québec, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia… That was all Algonquin land. The Algonquins are made up of 13 families. Some have been killed off, exterminated by the newcomers. The prophets came walking out of the ocean and walked at different times.

First prophet came and told them they had to leave and move inland to a turtle-[shaped] island. The Megis shell would guide them. “You have to leave the area,” they said, “because you will be killed off,” because they saw that white-skinned people would kill them off not through war but through disease. Because we were here through time immemorable, I can’t give you a time or date. They told the Indians to go. Of course, the Indians laughed and said, “Ha! How could anyone kill us off? We’re healthy!” They didn’t even know diseases.

They said, “Brothers will fight brothers,” and the Indians laughed and said, “Ha! How can we kill our brothers? Ha!” The prophets were god-like people. They said, “You’ll kill your families.”

The last one that came had green/blue eyes. Coloured eyes. He looked funny because all people had brown eyes. The last ones who came were two brothers. But Natives usually listen to their prophets. They said, “Take your scrolls.” They had scrolls made of birch bark with pictographs, and belts with colours, and stories told on them with green for trees, blue for sky, red could mean blood or fire. Red is a sacred colour, too. I don’t know all the interpretations, you know. I am still young. I am still learning. I am still a student. There is no end to our learning. We’re never completed. It’s like the more you learn, the more you need to learn. Like you get dumber and dumber.

A lot migrated and travelled like this, and some stopped in Ontario and called themselves the Three Fires Society. Those are Algonquin People.

The Ojibwe language has not changed much in centuries. Centuries! Can you believe it? Just maybe the slang is different. You learn all the words I taught and you can talk to twelve different languages. You can communicate. I taught you sign language and how to talk slow with tenderness to children, a sweetheart, mother, even God, to plants and animals.

It’s good to learn the language. You’ll learn the secrets. You have to know the history and worldview before you can really learn the language. But I have to teach my own way. University people were trying to make me teach their way with the sounds, verbs – we don’t have verbs in our language. We don’t have words like goodbye, blessings, or fear of death. We didn’t have that. I have to do it my way or I won’t do it at all.

That’s what I got from residential schools: do it my way, or no way at all. My Ojibwe way. That is not egotistical. It means I have a right to teach the way my ancestors did. And for that, we are [considered] bad. I was a bad girl at school. I was bad. My mom was bad. But we were bad because we did it our way. So residential school made me more protective of our culture. I have to protect it. I have to teach it. But I did lose a lot.

SK: What do you see for the children, the coming generations, the plants, animals, the earth?

HCQ: What do I see for the future?

SK: Yes.

HCQ: I see for the future a lot of confusion and continued destruction of the planet, Mother Earth. That’s all of our Mother Earth, because we came from that and we are going back to that. We came naked and we go naked. We cannot own anything. So we cannot – did not – sell you the land.

People have to learn the way of life of the First People of this land, and you have to recognize it. You can’t get away from it. You have to recognize and learn it in order to reverse the destruction that is happening now.

So my name is “Woman Who Walks Two Roads.” The newcomers have to learn that there are two roads in life: the good road and the bad road. Just like there are two gods. The good god and the bad god, and each god and each road deserves respect.

You have to respect both of them equally or they will destroy you. The good god can destroy you just as much as the bad god can.

So the Ojibwe way of life can teach all of society now that there is a spiritual road and a technology road. The positive and the negative roads.

People must choose one of those roads. If we choose the technology road, we are going to destroy the Earth. It’s already destroying. We’re not going to live here more than one thousand years. But if society chooses the spiritual road, we can live on this earth a long time and the eighth prophecy fire will light up. If we choose the spiritual road, we can live here a long time. Not we, but the human species.

But it is a slower-paced way of life.

Note: Ms. Cote Quewezance’s Master’s thesis can be found at

https://ecommons.usask.ca/handle/10388/etd-06052008-100527

1 Editorial note: Ms. Cote Quewezance refers to European settlers and colonizing forces in Canada as “newcomers” and “immigrants” in her interview.