If you were to ask me how my summer went, I might answer you that I traveled to Portugal, to Porto, the city of my birth, and there, for the first time, met family members whom I grew to love quickly and naturally. Weeks later, I came back to Montreal, a city in which I have lived for 47 years, or for most of my life, to be suddenly faced with news of yet another chapter of the Israeli-Gazan conflict. The first experience was stirring, and it nourished my soul and made me feel stronger than I had ever felt before; the second—because it features warring parties with which we have all grown up and learned to know well—darkened my days, and, since I tend to have a hyperactive mind and a tendency toward insomnia, my nights. Coincidentally, towards the end of the summer, I found myself having to conduct research into three canonic works of literature: The Epic of Gilgamesh, Genesis, and The Odyssey. On the news, the death toll kept rising; in my professional life, I circled the Mediterranean basin, unpacking texts from Mesopotamia, Judea, and Anatolia. By the end of the summer, when a friend and colleague asked me how I was, I responded that it appeared I was stuck in the Middle East. “A sentiment shared by many these days,” she replied, deadpan.

I hope the spirit of Edward Said will forgive me if I use the powder keg that is the current Middle East, and our collective need to escape and transcend its relatively recent expressions of extreme violence, as a metaphor. The Middle East is, of course, a real geographic region upon whose mountains, valleys, and coasts human beings live, hope, dream, and—if they are lucky—love, marry, have children, and grow old. But to me, this past summer, the embattled and distressed area also became a metaphor for our urgent need to think our way out of war and make peace.

“Why War?” Sigmund Freud asks in a 1932 response to a letter from Einstein. The question is somewhat rhetorical, for Freud outlines the steps from war, or what he calls “brute violence” to peace (10). Those steps include recourse to laws passed by a community of nations and, more personally and immediately, love—the love one may show one’s proverbial neighbours—as well as education and “a straightening of the intellect, which tends to master our instinctive life” (13). All of Freud’s solutions reveal both sense and sensibility, but the one I wish to address here is the last one: the use of intellect against the irrational ravages of war.

During the Israeli-Gazan conflict, I noticed the extreme polarization of our city. There were rallies in support of Israel and rallies in defence of the Palestinians of Gaza, but this and other cities failed to rally in support of bilateral or reciprocal peace. One felt as if war were a football game. Closer to me, friends I first met 30 years ago when I attended university in Montreal fought tooth and claw as some backed Israel while others demanded human rights for the Palestinians trapped in Gaza. What surprised me the most, perhaps, was that we had all gone to one of the “ivy-league” academies of the North, and there we had been schooled in careful argument and taught that intellect matters because it sheds light on darkness. But what I heard instead were weak, clichéd arguments crystallized around sclerotic catch-phrases that bordered on propaganda; for instance: Israel has a right to self-defence. All countries do, of course, but nobody was willing to examine exactly what that entrenched legal right consists of. Another worn-out and much-used statement on the other side was that Hamas never uses Palestinians as human shields. Perhaps Hamas does not obviously or directly use Palestinians as human shields in the way human shields were reportedly used during the Second World War or in the former war in Yugoslavia, but according to the United Nations Relief and Works for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), Hamas did hide weapons in strategic places like UN schools—those very schools where refugees from the bombing sought temporary shelter—and it has since admitted having fired rockets from residential areas, according to The Wire’s Adam Chandler. Not to excuse these acts (I couldn’t), but the question nobody asked was this: where could you hide anything securely in a minuscule, over-populated territory called a “strip”? Or, perhaps more responsibly: are violence and war the only solutions to this conflict? And then, too: who profited from this mess?—because where there are weapons, there is financial gain. People, then, who had been schooled in rigorous thinking were forgetting to inform themselves and reason at a time of tremendous crisis. Suddenly, too, persons without prejudice in their heart were being called anti-Semites for taking sides with Palestinian civilians against the government of Benjamin Netanyahu. But aren’t the Palestinians also a Semitic people—does that, then, make the hawks in the Israeli government equally “anti-Semitic”? Words were being tossed about negligently by people whose fine education required that they use words and rhetoric with greater knowledge, logic, and conscientiousness.

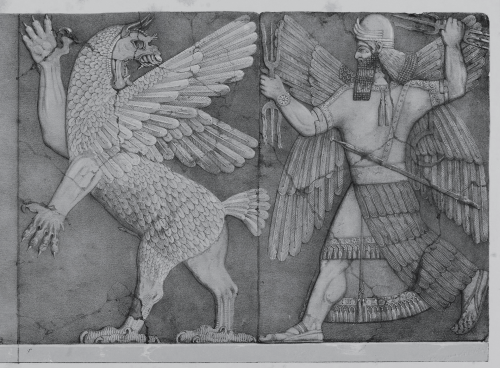

As I was noticing this failure in clear discernment, I ploughed on, reading Gilgamesh and crucial passages from the Torah. I had never read Gilgamesh before, so the text came to me as an enjoyable surprise. American legal scholar and philosopher Martha Nussbaum is of course right when she claims boldly—at a time when the Humanities are in the crosshairs of those who would have them disappear because they fail to satisfy the immediate, short-term needs of the market—that literature civilizes. I was charmed by the perpetually misguided King of Uruk, who thinks that his power gives him the right to behave badly and then believes he ought to seek fame and glory, and then immortality, before he is advised by a minor goddess to simply relax, seize the day, and enjoy his life, which causes him to return home and wonder at his accomplishments within the city where he reigns. Presumably, the city will outlast him and be the only form of immortality he can count on. Let’s face it; we are, The Epic of Gilgamesh teaches us, first and foremost earthly. Our days are counted. One day, we too shall become dust, and before that happens, the epic tells us, maggots—yes, I know—will crawl out of our nostrils, as one exits his deceased friend Enkidu’s nose.

The myth of Adam and Eve isn’t any cheerier. We pay for our autonomy and free will not only with mortality, but with pain. God warns his favoured prelapsarian couple that they will die if they eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. The rest is history but, surprisingly, they do not die immediately; instead, they are cast away to live a mortal life filled with pain: man will learn to work hard to survive; woman will give birth in agony. God’s fateful promise to the bewildered transgressors was no joke, as it turns out: from Cain to Noah, to Isaac’s near sacrifice and Jacob’s terrible injury at Peniel, man toils, doubts, agonizes, prays for deliverance and mercy, and cries out in pain. To our mortality, Genesis adds suffering. We are mortal and as we live, we suffer.

The Odyssey takes the first step out of this bleak predicament. The characters of Odysseus and Penelope remind us that we are mortal, that we are condemned to sorrow in this life, but that cunning, intelligence, and resourcefulness can get us out of many of our binds. Because the trauma of the Trojan War never stops rippling through the characters of The Odyssey, neither Odysseus nor his wife relax their vigilance for more than an instant as both urgently attempt to think their way out of their misery and difficulties. Trained in war and anxious after twenty years spent away from home, Odysseus at times deals with his problems by thinking his way into violence, but his wife, Penelope, the weaver and unweaver of looms, is the true diplomat. Even at the very end, when her husband stands before her, bathed and restored to his former majesty, Penelope tests him gently for fear that she might be tricked by the gods and walk off with a suspicious stranger, as Helen did with Paris, plunging her countrymen into a decade of war. Penelope never quite puts it this way, but, hey—better safe than sorry, or better smart than shamed, dead, or dead wrong.

In none of these works is war presented as a good idea. As King Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu launch an attack against the ogre Humbaba, they are cursed. Cain’s personal and murderous vendetta against his brother Abel leads to his branding and exile. Odysseus, we feel, would have enjoyed a contented life on his estate and had a few more children with his desirable wife had he not gone to war to get that adulterous woman, Helen, back home to Sparta. If Odysseus makes it back, if his nostos is successful, it is only because he is resourceful and clever, and he grows smarter still. Having learned from his appalling moment of hubris as he escapes the Cyclops Polyphemus, he later instructs Telemachus, his son, that “It’s light work for the gods who rule the skies / to exalt a mortal or bring him low” (16.241-42). The gods may crush us like ants, and what is needed to live a good, long, and safer life is a capacity for moral conduct coupled with a whole lot of hard thinking and mature reflection. Unfortunately, Odysseus goes on to slaughter all of his wife’s suitors and threatens further carnage when the Ithacan families demand reparation, but Athena stops him and warns him that the wrath of Zeus will be upon him if he keeps at it. When Odysseus obeys her and chooses peace, it is, we are told with joy and—one imagines—tremendous relief in his heart.

Life being subjectively short and at times pointlessly painful, then, wouldn’t using our minds to get out of war, not to mention weak and stale arguments born out of blind loyalty or solidarity, and into a lasting peace prove a worthwhile project, something one might proudly leave behind as a significant legacy before one shuffles off these mortal coils? The alternative is grim. The injustices committed by the fathers, the Book of Exodus tells us, might well be revisited “upon the children’s children, unto the third and the fourth generations” (34:7) Gandhi’s alleged statement that “an eye for an eye will leave the whole world blind” makes the point a little more graphically or, as one of my law professors once told us (and this was a sobering thought even for the student I was then), for every year of war, a nation will need ten years of healing.

Hard thinking, unfortunately, was missing during the terrible events that came to pass between Israel and Gaza in Summer 2014, as opposing camps and, indeed, pundits on the very media we watch and rely on, lobbed blame back and forth without pausing to think their way out of horror. “War,” former war correspondent Chris Hedges writes, “suspends thought, especially self-critical thought” (26). Najla Said would concur. When bombed, she explains, it is the easiest thing in the world to “look up to the sky and feel abject, boiling hatred for the people doing this to you” (249). But we here in Montreal were not being bombed, yet we too succumbed to the same primary emotions. If we want to find a way out of the tragedy and shock taking place in today’s Middle East, if we want to achieve a sort of intellectual nostos into a life of integrity, responsible thoughtfulness, and peace, we had better heed the lessons of the Middle East of yore. If we fail to listen to the tales of Gilgamesh of Uruk, Adam, Eve, Cain, Noah, Isaac, Jacob or that of the shrewd Penelope, we might well find that to the mortality and pain that are man’s lot is added a complete inability to rise above calamity as we wallow in our own emotional and hackneyed responses without a foothold in rationality, correct information, education, the ability to act collectively in favour of peace, and ultimately—as Freud reminds us—love for our flawed but human and vulnerable neighbours.

Readings

Chandler, Adam. “Hamas Quietly Admits it Fired Rockets from Civilian Areas.” The Wire. 12 Sept. 2014. Web. 14 Sept. 2014.

Exodus. The Holy Bible. Authorized King James Version. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009.

Freud, Sigmund, “Why War?” Approaches to Peace. Ed. David P. Barash. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford UP, 2014. 9-13.

Hedges, Chris. “War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning.” Approaches to Peace. 24-26.

Homer. The Odyssey. Trans. Robert Fagles. New York: Viking, 1996.

Said, Najla. Looking for Palestine: Growing Up Confused in an Arab-American Family. New York: Penguin, 2013.

“UNRWA Condemns Placement of Rockets, for a Second Time, in One of Its Schools.” UNRWA: United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. 22 July2014. Web. 14 Sept. 2014.