(The following piece is based on the author’s musings and reviews of a novel, its sequel and its adaptation into a film.)

Someone is Killing the Great Chefs of Europe

A first novel by Nan and Ivan Lyons, published simultaneously in New York and London by HBJ in 1976. You might wrongly assume that most of the events occur in London or somewhere in Europe.

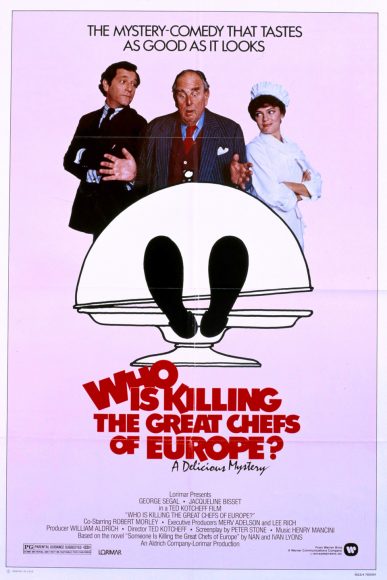

Who is Killing the Great Chefs of Europe? A Delicious Mystery

A 1978 film by Canadian director Ted Kotcheff. “Delicious” it is, not only for the chosen tone of comedy, but also for the exquisiteness of the recipes. Released in 1978, it became an immediate success.

Someone is Killing the Great Chefs of America (1993)

A sequel by the same authors. Many of the characters and events are borrowed from the first novel.

In order to avoid “spoilers,” I will use material from my previous writings to explore some comparative aspects of the adaptation of literary works to the cinema. After writing for half a century, I now find it difficult to avoid talking about myself. (One of the greatest French novelists declared that a good writer tries to make believe that he never existed.) Having to write in English (my fifth language), I feel more at ease talking about myself because I realize that the first person pronoun is always capitalized. Would that be characterized as imperialism?

Who is (are?) the actual culprit(s?) in both books and in the film? Please do not consider my initial question as a provocation, but as something to be taken literally, although ironically so. It could not be otherwise. Before deciding what to expect of a screenplay adaptation of famous mysteries – material previously read as literary text – many film fans might bet that some aspects (e.g., the perpetrators of the crimes, or their methods) would need to be modified. Sometimes accomplices are added in the film, and the dynamics are different. Sometimes the surprise consists in following the original text literally – but that is dangerous and should be done only once in a lifetime by an experienced director.

No matter what, my opinion will remain that of a dilettante. Although I have written books, articles and film reviews, organized and directed film societies, attended film festivals (the Mostra Internazionale d’Arte Cinematografica started in 1932 and the new Palazzo del Cinema was inaugurated in 1937), I was unable to find a reason for the special retrospective I myself witnessed at the age of eight, in the summer of 1938, held in the open air garden of the Excelsior Hotel at the Venezia-Lido. Who organized it and why there? I remember watching Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion. There was a second feature: Extasis by Machaty. A few years after, Luchino Visconi chose the same hotel to film Death in Venice based on the novella by Thomas Mann.

Who or what predisposed me to become a film fan at an early age? Undeniably my parents, since they both cherished films and opera. Every fortnight there was a lyrical drama, and there were ample opportunities to watch films, even on weekdays. My first collection of reading material was libretti for opera, issued periodically with a red cover, and I was in charge of cataloguing them. My mother was enamoured with Pirandello’s works, while my father puzzled over mysteries. Those came with a yellow cover, a colour so attractive that it became the designation for the genre. It is very rare in Italian for an adjective to be transformed into a noun that finds its way into all the dictionaries.

No one will deny that at the root of every film there is a text, which may be a short treatment, a fully developed script, a novel, a play, a story, etc. There are a few exceptions that confirm the rule. The most notorious is Andy Warhol, incessantly filming a building overnight in New York – he makes his point. Avant-garde movements all have to break the rules. In France in the 1950s, Isidore Isou and Maurice Lemaître systematized that practice, and the latter persists in doing so bravely to this day. Not everyone agrees on the literary importance of the script. Ingmar Bergman, one of the great filmmakers of those times, declared that cinema had nothing to do with literature. Visconti writes: “The author of a film is an author in his own right. The script is only a point of departure.”

One of my first articles about the literary origins of cinematic endeavours was written in Portuguese upon seeing Antonioni’s Blow-Up. I was so electrified that for the first time in my life, I felt nailed to my seat of that Rio de Janeiro movie house, compelled to watch the film twice in a row – a very rare occurrence. I now can’t resist narrating what appears to have been the conversation between the filmmaker calling from Rome and the Argentinian writer residing in Paris. Carol Dunlop, a very intelligent Canadian writer, picks up the ringing phone and tells Julio Cortázar that Antonioni wants to talk to him. Julio thinks that she’s pulling his leg, and doesn’t move. At her insistence, he finally complies. Antonioni explains to Cortázar that he was fascinated by the mechanism of blowing up images, but that he would do a different film. Julio, who is already a sincere admirer of Antonioni’s previous films, bows and approves. After the release of the film, Cortázar is interviewed and asked if he sees himself reflected in the film. He answers enigmatically: “we meet somewhere in the clouds…” but adds almost immediately that the film was magnificent. Indeed, Antonioni alters as many aspects of the short story “The Devil’s Drool” as he possibly can: the location of events – London instead of Paris; the characters – a mature gentleman and a younger woman seemingly married but not to one other, instead of an adolescent boy and a go-between for a predator of young flesh waiting patiently in a nearby parked car; and a professional fashion photographer instead of a Sunday-only amateur, etc. Moreover, Antonioni adds to his plot a crowd of characters that are non-existent in the written text. I analyzed the film in at least two academic papers that later became articles, in the hope of proving that Antonioni did the most intelligent thing he could in adapting Cortázar to the screen – instead of illustrating by sticking to the letter, he stuck to the spirit of the book.

As far as I am concerned, it is not up to me to conclude if I succeeded in convincing my listeners and my readers. The question can be reopened at any time, and here is the bibliographical data:

- “Blow-up from Cortázar to Antonioni,” Literature/Film Quarterly, IV, 1. (Winter 1976), 68-75;

- “Antonioni’s Interpretation of Reality and Literature,” Forum Italicum, XIII, 1, (Spring 179), 82-93;

- “Nouvelles perspectives comparatistes: Le Ciné-roman. Vers le ciné-roman et au delà,” Neohelicon (Budapest) XVII, 261-271. In it, Antonioni is quoted when commenting on his last book, Techniquement douce: ‘I was so involved in it that I thought that I had filmed it” (p. 34 of the French text, translated by me). The same article serves also to confirm my bias in regard to Marguerite Duras’ much more radical point of view than mine, when she describes issues pertaining to Le Camion and some of her own films.

The time has come at last to deal with the real crux of the subject. This long preamble was not incidental or a digression, for it gave me the excuse of showing how the great masters of the past have dealt with the problems of adaptation. Let’s begin with the book.

First of all, a mystery implies suspense, and that starts immediately and is constantly present. The authors should be commended for fulfilling this delicate and important task so brilliantly. Secondly, they chose to mix comedy and mystery, and one invariably laughs at every page.

The only cause for astonishment is the quality of language employed in the descriptions, contrary to the courtly vocabulary of British essayists who banned any allusion to sexual matters from their dissertations. But since both authors are Americans, they did not feel compelled to moderate their tone or hold anything back. How free we are from Victorian conventions on this side of the Atlantic, in allowing ourselves to indulge in violating old moral codes with very detailed incursions into anatomical items!

The characters are well developed and believable, despite some obsessive quirks.

The common obsession is with food, as the reader can tell from the title of the novel. The authors are generous in their haute cuisine recipes. One may even try out some recipes if s/he has time, patience, talent, and is able to find the ingredients. I don’t think I would spoil anything if I said that the authors devised a very original way of killing the chefs (whether they died or not), inspired by their own gastronomic specialty.

Here comes the film, and one cannot help but notice that the script is entrusted to Peter Stone, a veteran of Hollywood screenwriters, already famous for Charade, rather than to the two authors of the book (the point of departure for the screenplay). Ivan Lyons majored in film writing at the N.Y. Film Institute. That decision may be a coincidence associated with production, or a deliberate and significant choice. While the book exudes intelligence (diabolically so), the film director replaces that with human sympathy. The crimes are illustrated in a very vivid iconic manner, which increases the enjoyment. Driving the film are Jacqueline Bisset and George Segal, playing, alternately, a married then divorced couple. As they also produced the film, they obviously had first choice about the length and extent of their contribution. But already in the novel, Bissonette’s character plays the role of the easy nymphomaniac (motivated by revenge?). The fact that Jean-Pierre Cassel speaks English with a French accent when he is supposed to be Austrian remains puzzling.

A case of total miscasting was that of Stefano Satta Flores. I am sorry to have to express a negative view on a very excellent actor whom I happen to respect, and who died of cancer prematurely at the apex of his career – an actor whom I have applauded on the screen and on TV, and one who was at ease in any kind of a role. He is not to be blamed, but whoever chose him for his role did not know an old proverb describing the inhabitants of the three sub-regions that form the Republic of Venice. I will quote and translate only the first part, although the entire text applies to all the other regions. “Veneziani gran signori” implies being refined, polite, generous, intelligent, magnanimous, courteous, educated, appreciative of good food and of all arts and sciences, elegant, definitely trustworthy, scrupulous – a Renaissance man. Tall, without extravagance, treating women as ladies (even when they are not) and naturally charming. Since pinching ladies is considered extremely vulgar by the gran signore, he instead engages in appropriate bowing and well-choreographed hand-kissing.

The second novel features some of the same characters and some new ones.

The suspects are also some of the same. The traditional duty of avoiding spoilers prohibits me from disclosing the stroke of genius that inspired the authors to hide a new-old character and a new-old suspect. Let us add that this is not the only pleasant surprise that happens in the book; many other extraordinary new developments are introduced, all meaningful and unexpected. The authors themselves become characters, in a rather uncommon and very clever twist. The readers will uncover soon enough the enigma, and figure out what dictates the authors’ behaviour. They frequently prefer not to say things openly, relying instead on suggestion or inference. For example, they have studied and travelled abroad extensively and are well aware of culinary terminology. Yet they do not write a single sentence in Italian, French, German, Spanish, or Japanese without including some mistakes. They do this on purpose, to caricature the ugly American tourist with a fake Hawaiian shirt hanging down over inappropriately long shorts, sun eyeglasses, binoculars on his beer belly, attempting to order lunch in a foreign restaurant. The fact that the language is replete with four-letter words does not shock anyone any more, since that has become the prevailing style.

The authors are masterful at creating fast-paced suspense, and the moral of the two novels is a hymn to the couple. In fact, the husband seems to forgive his beloved wife and overlook her erratic sexual adventures. Is she telling the whole truth?