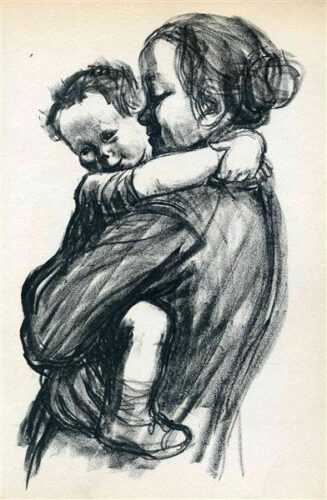

Mutter mit Jungen by Käthe Kollwitz, 1933 – Public domain

[Editorial note: Serai editor Rana Bose was intrigued by the autobiographical story submitted by Miriam Edelson, from Toronto. “Intrigued” would perhaps be the wrong word. It was more of a sense of resonance with a time in the past. Bose’s family and Edelson’s family, living in diametrically opposite corners of the world – Kolkata and New York – picked up prints of the works of German artist Käthe Kollwitz and were evidently moved by them, as were their children.

It was the Cold War era, and Kollwitz represented in many ways the voice of the silenced and the outward expression of many tensions – within herself, and with her surroundings. Her works reflected a myriad of despair and hopes. In the context of this issue’s theme, “Out of the Ashes,” Rana found it important to continue the conversation on Kollwitz’ art as a crucial exercise in remembering. His exchange with Miriam Edelson is found at the end of her story.]

The first piece of artwork I became aware of as a youngster is a charcoal print of a mother holding a small child in her arms, by the German artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945). Best known for her drawings and prints, Kollwitz chronicled in her work the lives of working people in the face of hunger, poverty and war. The modestly framed picture hung above the piano in our family’s living room. Later, it adorned my own home and in the years before becoming a mother, I would look at it with some yearning and a pinch of understanding. The relationship between mother and child was so clearly central to both, their mutual need and desire for the other so intense.

Kollwitz was one of my mother’s favourite artists. My mother was a social worker, familiar with distressed families dealing with hardship. I think it was the humanitarian political impulse in the artist’s work, the need to expose poverty and protest against the effects of war, that appealed to her. My mother’s training emphasized group work, rather than individual casework, an approach that reflected a systemic critique of society. People in her left-wing circles adored Kollwitz’s work.

At some point before my mother died, I discovered a treasure trove of Kollwitz prints safely ensconced on the shelf above her clothes closet. She had hung one print in our home and kept the others for her children, I imagine. Encased in a textured cardboard cover, separated by tissue paper that crinkled when touched, were eight drawings of children, women, and men. They were definitely not middle or upper class but rather, ordinary folk, several having fallen on hard times. The mother and child print that I looked at so often during my daily music practice found pride of place in my daughter’s room at our summer cabin. She grew up with it hanging across from her bed.

Another artist whose work spoke to me during my pre-motherhood days was the American Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), who exhibited in France with the Impressionists. Her paintings of young children playing quietly with their mothers still in bed, drinking coffee, drew me in. I yearned for such communion with my child-to-be. In fact, however, the idyllic moments of the privileged women Cassatt painted were quite unlike my own experience. It was not very often in my mothering of young children that such stillness prevailed.

❖❖❖

“No, I won’t get dressed for daycare,” my child wailed at me. She insisted on wildly running around the house in the nude at age four.

This was an almost daily occurrence. I once resorted to driving her to the daycare naked, wrapped in a towel, her clothes in my lap. We scooted up the steps and I dressed her – finally — in the staff washroom. I can’t imagine Mary Cassatt’s mothers going through such a tumultuous morning routine.

My connection to Käthe Kollwitz is different because she captures in her work something of my mothering travails. Her subjects are working-class or poor women, chosen from among those who came to see her physician husband, in a disadvantaged area of Berlin where he chose to practice. Kollwitz is not afraid of the hard subjects, grief and death. She lost her younger son, Peter, in the early days of World War I. I lost my boy to a neurological disorder just before his 14th birthday. I handled my grief, in part, by writing. Kollwitz created sketches, etchings and sculpture drawn from the same emotional landscape. There is a stunning authenticity to her work.

I wish I had taken the time to sit with my mother in her nursing home and go through Kollwitz’s wonderful charcoal prints with her. I think our sensibilities were similar. It’s too late for that now. We lost her to Alzheimer’s, and such special final moments were out of reach.

Perhaps I could have tried and she might have enjoyed some lucid moments with the pictures again. I’ll never know, but I think I will initiate some quiet time with my (now dressed) adult daughter to look at them together. She’s in that pre-mothering phase where the yearning for a child is beginning. She, too, might appreciate the humanity that emanates from Käthe Kollwitz’ work.

The Mothers by Käthe Kollwitz, 1922, sheet 6 of the series The War, woodcut, via Wikimedia Commons

Exchange between Serai editor Rana Bose and Miriam Edelson

RB: My questions have more to do with my sense of nostalgic association with Kollwitz in our family and the presence of some prints of her work in the ’fifties and ’sixties in India. My father had been to both the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) a few times. He popularized Käthe Kollwitz amongst his friends and colleagues. He was a cardiologist and a socialist. These questions may simply add a contemporizing element to your essay, which is very moving. As you know, during these times a lot of history is either being revised or forgotten.

ME: How wonderful that my piece found you, someone who also grew up with the presence of Käthe Kollwitz – and yet, on the other side of the world from New York where my family lived at the time. I’ll do my best to answer your questions based on what I’ve read about the artist and the times she lived in.

RB: Can you describe one or two of the other Kollwitz’ prints that you discovered as a “treasure trove” in your house? What were they all about? Could you explain the possible context that made her create those works? The reason I ask is because she not only depicted working people but also social movements. Could you describe those movements? It would be good for Serai readers to know more about her affiliations and leanings.

ME: I’ll speak about two prints I came across. One is called “Visiting the Children’s Hospital” and it depicts a man and woman (presumably the parents) leaning in toward a small child seated on a chair. The woman is holding a cup for the child to drink. The parents look both loving and concerned.

Visiting the Children’s Hospital by Käthe Kollwitz, 1926 – Artory

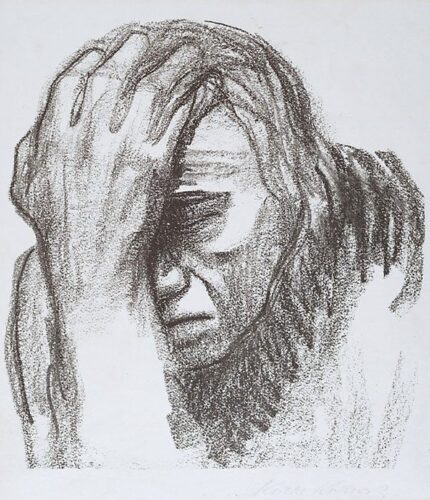

The second print is called “Woman lost in thought” and shows a woman who may be at the end of her tether, deep in thought with her hand covering much of her face. There’s a poignancy to the picture as she seems rather worn out by life. In both prints, I believe Kollwitz captures something essential about suffering and the human condition.

Woman Lost in Thought by Käthe Kollwitz, 1920 (Source: Addie’s art blog)

Kollwitz’ work documented the daily struggles of ordinary people, particularly women and mothers, but not exclusively. I understand that the period after World War I in Germany was particularly challenging in terms of widespread poverty and a great sense of loss after losing so many young men in the war. Kollwitz was active in the anti-war movement during these years, creating political posters for various organizations, including socialists and communists (although everything I’ve read said she was not a member of the CP).

RB: Dark, gray representations of social realism and human suffering were the essence of her art. Have you seen any that were different from such a representation?

ME: Most of the work I’ve seen in books and at the Art Gallery of Ontario follows this same representation. It is interesting that she did so in different mediums – charcoal prints, lithographs, etchings, and sculpture. I find the pictures of the sculptures to be quite compelling and would love to have the opportunity to see some in person. I understand that in Germany there are many streets and schools named after her, a testament to her impact.

RB: What exactly do you mean when you talk about your mother’s group work? Can you explain some more about that?

ME: What I understand about groupwork vs. casework is that my mom was both trained in and committed to the notion that structures and institutions in society determine outcomes for ordinary people. Two things come to mind. Today we hear a lot about the social determinants of health – housing, nutrition, socio-economic status (class), education and so on. I think my mother would support looking at an individual’s or a family’s situation by exploring those social determinants rather than assuming a deviancy or some other ‘blame the victim’ viewpoint. So, in addition to finding some relief for the individual or family, the social worker could be involved in community organizing toward improving the general conditions. Does that make sense? As a young woman, my mom was also involved in organizing some of the early social work unions where she was working in Cleveland.

I hope these answers are helpful. There is so much richness in the artist’s work and I’m not an art expert. But I know that the values my parents raised us with, to live in such a way that you are contributing toward creating a better world, were also somehow infused in Kollwitz’ work. And that’s what stays with me.

Tour des mères by Käthe Kollwitz, 1937-1938, via Wikimedia Commons

More on Miriam Edelson:

Miriam Edelson’s first book, My Journey with Jake: A Memoir of Parenting and Disability, was published in April 2000. Battle Cries: Justice for Kids with Special Needs appeared in late 2005. She completed a doctorate in 2016 at University of Toronto, focused upon Mental Health in the Workplace. “The Swirl in my Burl,” her collection of essays, is forthcoming in Spring 2022. To follow Miriam’s work, please visit her website and blog.

With a gesture. a line, a word, we can find how much more we are alike than not.