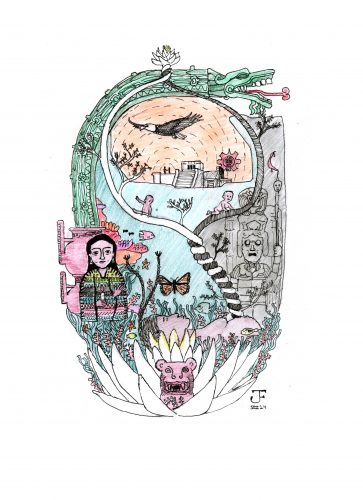

Illustration by Juan Fernández Gonzalez. Details below.

[The prehispanic part of the story is based on sociological findings and traditional legends. The modern part is based on fiction. Sac Nicte and Can Ek were the real names of the doomed lovers.]

They had told her she would come out on the third day. That is what the mediators of the Lords of Xibalba had led her to believe. At least, that is what they themselves wanted to believe. The hunger of their hollow power could only be assuaged with their own lies and delusions. It is true that the war of the heavens is the opposition between night and day. It is also true that the stars have to be conquered and sacrificed, so that the sun can drink their blood and the day begin all over again. In order to keep the universe in movement, people have to spill their blood so that it does not perish. But she knew them to be wrong when they said she would be out in three days. She had grasped this truth as firmly as she had grasped and held on to her mother’s breast soon after she was born.

Her birth had been auspicious. She had exited the real world of the void to start her journey through the world of illusion on 12 Baktun, 16 Katun, 8 Tun, 7 Uinal and 5 Kin, under the round and radiant face of Ix Chel, the moon goddess who wanders endlessly through the dark night so that the sun, her consort, does not burn her into oblivion.

It is to Ix Chel’s care that her own mother entrusted her, shortly before she was sucked back into the vortex of creation. Her poor mother, who had to pay for the honour of birthing her with a torrent of sacrificial blood that drained her body as her hungry child drained her breasts dry for the first…and the last time. At least her mother had been transformed into a lovely butterfly which is the reward bestowed on a brave who dies in battle or a woman who exchanges her own life for that of her newborn child.

This is one of the many truths that she understood but failed to accept: that men are rewarded for destroying life and women for creating it. But that seems to be in the nature of all dualities, for how can we see the radiance of goodness when there is no shadow of evil to set it off?

Birthing her had indeed been an honour. It was written that this female child born under the sign of Ozomatli, the monkey who invented fire, was to be a great medicine woman. So the midwife swaddled the baby carefully in her mother’s blanket, hurriedly buried the cord that tied her to her unborn twin in the very centre of the house, and stole into the night, with a little bundle in tow. Under the complicitous gaze of Ix Chel.

The midwife had acted out of kindness, for she knew that power is a good and strong thing, but not before its time and not in the wrong place. Before its time, power can turn upon itself, which, in this case, would hurt this lovely child who would now be hers. And when power is used in the wrong place it can be misused by the enemy. For the midwife knew that she alone could pass on to this child the knowledge that she had acquired from the Final Mother, without any interference from the child’s father and his high-born clan.

So she was named Sac Nicte and was brought up in the neighbouring temple city of Tulum, where the breeze blows cool air from a turquoise sea and children grow big and strong. Sac Nicte grew to be as pretty as her namesake flower and as strong as its fragrance although her secret name was to remain hers alone. It is in her secret name that she nursed her power while it grew and took shape, whereas her public name only held her outward appearance, which, by the way, enchanted many men and made the maidens envious.

But Sac Nicte paid scant attention to her body or her face. At least, not in the way it was expected of her. She had been nursed by a kinswoman of the midwife until she was about three, when she playfully started biting the very breasts that had made her teeth so strong. Her nurse, who had many children of her own, was glad to wean this strange child and send her to her Tata, the midwife. Under her Tata’s loving hand, she grew up to be wilful and sure of herself.

It is thanks to her Tata that no pebbles were strung from her soft baby head to a midpoint between her eyes, to make them crossed. Crossed eyes might be beautiful, but she needed to see straight for the arduous tasks that awaited her. Her teeth were also spared being polished with stone and water to make them sharp like the teeth of a baby shark. It was also her Tata who refused to encase her forehead between two planks of wood, to give her the gallant elongated look of the temple friezes. For that she was very grateful. In any case, she did not intend to carry heavy baskets slung from her forehead over her back. She did not know why, but she sensed that the source of her strength and her understanding lay somewhere behind her forehead, in a point between her eyes. After all, she had observed that people fall into a deep dreamless sleep when they are hit hard on the head. And babies whose heads get stuck in their mothers at birth often grow up to be dull.

Sac Nicte was not vain but she was sensuous. She liked to sit at her Tata’s doorstep and allow the old woman to oil her hair and braid it into two long braids that fell all the way below her waist. And after bathing in the sea, she would rinse herself in sweet water and anoint her body with pungent red resin which would start a fire in her loins if she happened to be thinking of him.

His name was Can Ek and he was a son of one of the Lords of Xibalba. Can Ek was as tall as she was full and his skin had the burnished look of a dying sun. His mother had burnt the roots of the scanty hairs on his face before he reached his manhood and now his face was as smooth and soft as hers. His lips were round and red and his eyes were as black and as sharp as an obsidian knife. So was his rod.

He had come from far away to visit his kinsfolk and to plunge into the jade sea and he had plunged into her soft flesh instead and tasted the salt on her lips. The first time she had felt him inside, she had cried out in pain and the blood between her legs was not the blood that was preordained by the rhythm of the moon. After that, she had marvelled at how he could be hard and soft at the same time, a lesson she, as a medicine woman, still had to learn. At times she imagined that what she held in her hand was a plantain that was not yet ripe; at others, she accused him of being like a slippery eel not wanting to be caught.

But his very beauty was her undoing. They said that he had an evil streak. How could it be that she, a medicine woman, had not detected it? They said that when he turned seven, he killed a butterfly, who could have been her own mother! And at fourteen he had killed a deer, merely to possess the gland which holds the secret of all life. But as a grown man he had met Sac Nicte and his eyes filled with tears. A man who could be thus moved was a man to cherish.

He was her undoing not because he had shown the cruelty that was often mistaken for courage and expected of men, nor because their limbs had entwined around each other like the roots of the mangrove tree but because he was her kin. At least, that is what everybody thought, except for herself and her Tata, who knew that it was not so. It was carved on stone for eternity to see that no man and no woman was to come together with a member of the same clan.

“You must be good at making corn bread” he had said, as he stared at her while she bathed in the river. “Those breasts ripe for children are only given to those who grind corn every morning of their womanly lives.”

Sac Nicte had smiled and stared back at him, not making any attempt at covering her private parts.

“I do not make bread at all” she had replied earnestly. “I am a medicine woman. I can help women in childbirth, remove warts and help people polish their shields against their enemies. I can also call on Ashana to keep the evil spirits at bay. I am good at helping people find their secret twins to translate their dreams and visions. I can also weave as fine a cloth as the gossamer web of a spider and fashion quetzal feathers into adornments fit for a queen. I can even count in twenties and predict the movement of the heavenly bodies. I can do that and a lot more, but I cannot make bread. That is not my calling.”

Can Ek had remained silent. Knowledge is recognition and Can Ek had recognized her and this is why tears had streamed down his face like the first rains of summer. The Lord of Dualities had decreed it so. A man and a woman must join each other just like the water of the earth ultimately meets the water of the heavens in the distant horizon. This was the woman who was his true opposite and the twin of his soul.

Sac Nicte recognized him too. She had seen him many times even without the help of sacred mushrooms or generous portions of the brew prepared by the goddess Mayahuel. She had seen him and she had imagined the feel of his smooth skin but was not prepared for the richness of his voice or the headiness of his scent.

It was then and there that they had touched for the first of many times, before he even knew her name, before she had pulled him by the hand and taken him home to her Tata.

“I want the priest to tie our tlimantli and if he will not do so, I will do it myself”, she had announced in a defiant tone.

“Have you gone out of your mind!” her Tata had scolded. “He cannot marry into our clan because he is a kinsman of my brother.”

Sac Nicte smiled and leaning over towards her Tata, grabbed the old woman’s feet and squeezed them gently. “Didn’t you tell me that when my mother died you took me away from my father’s clan because their rank would not have allowed a child of theirs to have become a medicine woman? Didn’t you once swear to me that even though there was nothing more in common between us than the bonds of love and wisdom you were willing to spill your blood to spare mine?” I’m not asking you to spill your blood for me. I am merely asking you to help me meet my destiny with Can Ek.”

The old woman nodded. “If I reveal your origins, the priest might be willing to bless your union, but your father will claim you first. And then I will lose you and you might lose your man. You must go away, my child.”

Sac Nicte held the old woman in a tight embrace. “You cannot lose me ever, Tata. You were the one who taught me that essential life and love can never leave you, because you are that.”

Three nights after that conversation, Sac Nicte and her lover left Tulum and made their long journey to Chichen Itza, under the cover of a dormant Ix Chel. In Chichen Itza they hoped to blend in with the crowds that had thronged the sacred city to celebrate that moment when the day and the night are of the same duration, before winter arrives. It is known that on that day, as the sun moves over the horizon, the shadow of the great plumed serpent Kukulkan, Father of all of the Maya people, makes his ascent in seven laborious segments up the steps of the main pyramid. When he reaches the top, on the 365th step which marks the completion of a solar year, a new cycle begins.

So Sac Nicte had arrived in Chichen Itza, with her man and their meagre rations of dry bread and peppers and ground chocolatl and some honey and a gourd which they filled with the sap of the maguey cactus to quench their thirst along the way. And they stood there in front of the pyramid, marvelling at the sight of Kukulkan and dreaming of a new life for themselves.

But love had made Sac Nicte drop her guard. It is there that the mediators of the Lords of Xibalba had grabbed her and dragged her across the main square and taken her through the paved road that leads to the sacred cenote of Chichen Itza. She did not need to be a seer to know what awaited her. Nor did she wonder about Can Ek’s fate either.

Can Ek had tried to stop the men from leading her away, but others had materialized from nowhere and dragged him away too. Except that they had taken him up the pyramid, where Lord Kukulkan had snaked his way up in an eerie play of light and shadows, and gouged his heart out in a deft cut with an obsidian knife, as dark and sharp as his lovely eyes.

Sac Nicte stood before the cenote while the priests droned their worthless drivel. She knew why they had chosen them to propitiate the gods. They were recognized for their uniqueness in spite of their anonymity. She understood that to be different means to share the fate of kings, who are destined to taste the bitter drink of sorrow. So Sac Nicte and Can Ek were called to return to the whirlpool whence the powers of the universe have evolved.

She understood the hidden designs of nature and the eternal fires within all things. She also knew that the priests were wrong. They had told her that she would return within three days but it was not true. Nobody ever returned from this cenote, which was a well so deep and green and airless that even the fish could not live within.

But Sac Nicte also knew how to count time and read the stars. She understood the circular nature of time. Time was really like a spiral, like a whirlpool, that sucked you in and down until you resurfaced again, but in another form. When you measured time by the moon, you could count your holy days and when you measured it by the sun, you could calculate the seasons of the harvest. But everything started all over again every fifty-two years. More than the sum of her age and that of Can Ek’s but less than her Tata’s.

Just as childhood and youth are the promise of form and old age the ruin of physical form, death is the fall into formlessness. Life begins with surprise and ends with questioning. Would Can Ek’s heart live on in an eagle or a jaguar? Would her formlessness take on another form, and if so, when?

All these thought forms disintegrated at the very moment in which she was thrown into the green pool. Before she went back to the liquid womb of the Great Mother. Before she left the dry world of illusion to return to the liquid depths of the primal source.

The water felt warm and soothing against her limbs. It seems that she swam and swam forever in a wonderful underground grotto which was mottled with light from holes that looked up to an azure sky. The sea bed was carpeted with undulating coral which swayed gently as fish passed by. The colours were pink and yellow and blue and green comparable only to those you get under an electron microscope. The vaulted ceiling of that grotto was dripping with stalactites that looked like the strings of sugar candy of her Mexican childhood.

She was glad that she had conquered her irrational fear of water and learned how to scuba dive. A holiday in Cancun without this vista of marine life was unthinkable, honeymoon or not.

They had finally made it, her Kanuk and herself. They had met in a sociology congress in Mexico City and it was love at first sight.

Marriage had really been quite beside the point. But the Mexican government did not issue work permits to foreigners unless they were married to Mexicans and her Kanuk often spoke longingly about his home in Oka and his job in Ottawa with the Council of Native Peoples. They decided to commute back and forth, like migratory birds, until the children arrived.

So they had married to please their respective tribes and meet official requirements. This is why they were in Cancun, in a pyramid-shaped hotel where the food was good and the crowds abominable.

Their one concession to their sanity was staying as close as possible to the sea and visiting the Mayan ruins.

So this is how Maya came to be swimming in a lovely grotto which formed part of a network that turns into subterranean rivers and feeds the cenotes.

She got out of the water, dried herself and applied coppertone on her body before lying next to Kanuk. It never failed. The slippery oil on her skin and the sun beating on her pubis always seemed to arouse her. She turned to one side and started tracing the moon-shaped scar that Kanuk had under his left nipple with her index finger. She then pinched his nipple gently, noticing that it had already hardened.

Kanuk stopped pretending that he was asleep. He kissed her hungrily and seeing that there were not many people around, he eased his shorts to one side and penetrated her right there near the ruins in Tulum. They then fell asleep in each other’s arms, like the tangled roots of a mangrove tree.

When Maya woke up, she started tickling Kanuk’s face with a flower that was lying next to them.

“Stop it”, he said, “or you will get me started all over again!”

“Thanks for the lovely flower” she whispered.”I didn’t notice when you got up to get it.”

“I didn’t. Someone else must have given it to you.”

“You mean when we were making love? Or asleep? Look around you, the beach is almost deserted.”

“It is a strange flower. I’ve never seen anything like it. What’s it called?”

“It is called Sac Nicte”, replied Maya. “They say there was once a Maya princess by that name who ran away with her lover to the forest of Peten, fleeing her father’s wrath. When she died, this flower sprouted all over Chichen Itza, commemorating their love.”

“Why do you suddenly look so sad, Maya?”

“I just had a strange and haunting dream in which I recognized myself a long time ago. Tell me, Kanuk, you have never explained how you got that scar under your left breast.”

“Oh, that, it’s nothing really. When I was a kid in the reserve, my friends were always taunting me to prove my courage by pushing me to go deer hunting with them. I just couldn’t bring myself to killing anything, so one day just to show them I wasn’t a coward I took a jagged can top and cut myself hoping to gouge my heart out. Fortunately, I botched it up and the ambulance had to take me to a hospital in Ste Anne de Bellevue to get it stitched. Now that I’ve told you my secret tell me yours: who gave you that flower? Was it the guy who was ogling your breasts this morning?”

Maya kissed him gently on his round red lips and shrugged her shoulders.

“It was Sac Nicte herself”, she finally said.

“Who?”

“Sac Nicte, my secret twin.”

THE END

[First appeared in “Voices and Echoes, Canadian Women’s Spirituality,” published by Wilfrid Laurier University Press for the Canadian Corporation for Studies in Religion, Kingston, Ontario 1997]

Note for the Illustration by Juan Fernández Gonzalez

The circle of life is oval shaped, a woman representing the creating of life. The grandmother, or tata, is plaiting the girl’s hair. The plant/umbilical cord comes out of the belly of the pregnant woman, with two branches denoting secret twins, a baby in each branch. The Sac Nicte flower is at the top and the bottom, serving as the cradle of the woman.

There is a jaguar sculpture and, in the sky there is an eagle (brave men become eagles when they die). In the centre there is a butterfly, which is what women who die in childbirth become. There is Aztec art from which Kukulkan (the serpent god) arises. There is coral to the sides, and small fish. The Lord of Xibalba (death) is depicted on his throne in grey tones. With his weapon he makes a moon-shaped cut. The sun is to one side in the sky, moving behind the Chichen Itza pyramid where you can see a man and a woman. Everything except the image on top is in a cenote (deep natural well) like the liquid womb of mother earth. And of course, at the bottom right is the signature of the artist.

Born in Manhattan and raised in Mexico, Juan Fernández is currently

exploring, studying and living in Montreal. Art is amongst his numerous interests.