Jaswant Guzder is an internationally-renowned transcultural psychiatrist, a psychoanalyst, an associate professor at McGill and the head of child psychiatry at Montreal’s Jewish General Hospital. She is also a visual artist. Born in British Columbia, Dr. Guzder is of third-generation South Asian immigrant origin. She moved to Montreal in the late sixties to study medicine and psychiatry at McGill. I first met her in 2008 during the launch of my second book. Her recent exhibition, Exile and Attachment, was motivated by the threat of erosion to human rights presented by the Charter of Values.

Interviewer: The general feeling in Exile and Attachment is that of inwardness. At the same time there is a strange outwardness and traces of the cosmic. It seems so many space-times, architectures, objects, emotions and trembling landscapes have either been absorbed or rejected by the bodies in your work. Walking through the exhibition one hears a painful hum: “I am vulnerable. No, I am not.” Is this an appointment with unresolved pasts? Interplay of felt and unfelt thought? Misfoldings of memory? Trauma?

JG: The work is speaking of mental states, stories of psychic worlds, psychic wounds and the need for survival in attachment are narrated in the work, as best I can transmit them. But, memory, whether it is personal or transmitted or absorbed always seems to come into any work in retrospect. Felt unthought is of course Bion’s unique formulation that is so useful in understanding emotional worlds and levels of memory in the body and mind. We know by feelings far before we can mentalize by works “the felt unknown,” and we so feel illuminated or renewed when the knowing is available to us in words or art.

Sometimes it seems to me that painting is just a process of energy transmitted by making the created object, it is a meditation experience.

Working with a Zen monk Kaz Tanahashi in Montreal helped me to reflect in part on what you are asking me, but that was after making these works. There was an awareness of that magical process: that moment of quiet between white paper and the start of that energy of a movement that comes to rest in the line and motion on the page. It was something he taught us to be aware of: silence, energy, motion and line all together a process. I found it so energizing to work in silence in his workshop, as one does alone in the studio or at any place of making. Whether there were others there made no difference as it was all about energy and the flow onto the page. With Kaz the object is meditation as painting or calligraphy exercises, the centering was on creating a letter of an alphabet usually a Chinese character. But my usual vocabulary is the human form or the face in this series. And I never know what the form will do. Here I have presented the entire series together for this show for one last time (as now some are sold or gone from the series). One colour makes it more powerful and uninterrupted as a flow, which may be how I am associating this with working with Kaz.

Are these notes, letters, energy? I don’t know. I simply felt compelled to make them, like a writer feels a need to share a story in words. Drawings are also about space and line dancing over a blank space. It is only later that I might attach a meaning of a mental state, when I can stand back and really “see” the drawings.

Interviewer: One is especially struck by the face in your work.

JG: This brings up self-representation, gaze and mentalization. Afterwards one sees: deadness, aliveness, repetitions, relationship and gaps. It is not so obvious why the blank page is filled with these faces. We are facial oriented from infancy to attract a reciprocal relationship. What if your mother doesn’t want you, or is ill, absent , tired, depressed? Is this face a face that is remembered, doesn’t respond, doesn’t look at you, always sometime it is looking somewhere internally. What if you find yourself in a country that does not want you? What if you lose your country or the place of your initial belonging?

I remember watching people closely as a child and many of my key people: grandparents or parents were not people who often had conversations with me. My clinical life is all about having conversations. But in my childhood I felt I was intuiting their lives and thoughts, sometimes I had the privilege of hearing their stories: especially my grandmother’s and my father’s India stories. These stories were impressed upon me that ‘felt’ state, in contrast to the place where I was living a continuous river of experience, that they were partly living in a place of exile that was my home. The place where I felt the wind and walked the forests of Vancouver Island. I formulated only later that I suffered an illness of nostalgia as a third generation immigrant. Salman Akhtar’s work [on immigration and trauma] helped me to formulate this reflection.

My mother impressed upon me that she had endured, that she had a traumatic childhood, marked by the war and the Depression, a cultural rift, a psychotic mother and many other things. At least this was what she conveyed to me, a worry and frantic effort to put that past behind her with a great resilience and determination to build a present. Yet as her first daughter I arrived at a difficult moment in her life. These feeling states were imprinted on me as a past or which I was responsible for in some way. Undoubtedly these early experiences impinged on shaping my own psychic illnesses, creativity and my journey as healer and painter. I would say it also asked me to address inconsolable grief at a young age. Is that why the face is rather mysterious and fascinating to me?

I am always absorbing, translating and looking at nonverbal in the work I do. So many clues are not in what people are saying with words but where their face and body is positioned. In the clinical space, one has to sort out the essence of these communications. We are accessing the authentic out of all this noise, and this is so much easier with children than adults. That is some kind of quest for meaning I suppose, and endlessly interesting to me.

Interviewer: You are the first one who told me about psychic skin. What is the difference between skin and psychic skin?

JG: The first one is the real and outer layer of a body. Skin is so important for love, touch and feeling. It may even erupt when feelings are stirred up sometimes.

The second one is what Esther Bick wrote about, the ‘psychic skin,’ it is the first sense a baby has of being in relation with the other and held together as an entity, a ‘psychic skin’ she called it. Sometimes a skin develops in relation to a particular mothering or fathering experience, a muscular skin she called the relationship with a very active and intrusive kind of interaction. Soothing, cajoling, holding, tenderness, quiet, abrasiveness or calmness of the parent form the “skin.”

Refugees in exile and migrants are developing a new psychic skin when they change places.

Interviewer: Talk a bit about creation of this work? Did you work at home? How long did it take?

JG: A few of the first series were done in a friend’s studio on eastern shore of Nova Scotia. Some in my home in Montreal. Usually quickly and at once, several or up to 20 at a time.

Some were inspired by drawings I have made on bits of paper while travelling. I bring them home and rework them.

Drawing series have happened in many places. I might work say at a friend’s table. I did so many pieces listening to people speaking in lectures or conversations: a way of transcribing what I heard.

The exile drawings are tender and vulnerable, they come from a deep aloneness I sense in others and sometimes an inner state of mine. And other feelings from holding my patients or failing to hold people in my life: I feel deeply wounded that I have not held them as I should have. Are the paintings an unfulfilled wish I could have held them more kindly, closely and comfortably, I feel such a sense of failure… babies who need to be held and were not held enough: at least that is how I see even many of my adult patients or child patients, those in need of being held. Did I have enough to give them or as a child to survive them? I have always felt the inadequacy of that gap between presence and closeness and distance. Refugees in exile have come to my office or encountered wherever they are out there, sometimes debilitated sometimes resilient. But many many times I have failed them, sometimes I have helped them. These are personal drawings. When people give you stories they are still residing in me as unfinished business, striving to move with the agency of stories, or sharing experiences with my fellow travellers through these series of drawings.

Interviewer: There is an absence of place in your work.

JG: Not true. Only some works are floating, rootless, homeless, incomplete, unsituated, soul destroyed or survivor focused, all life focused, as we are in outer space or exile or when we lose a beloved person, country or being in the world/place is there. But maybe you are right to say there is no place, but a void in this series. A refugee or a person in exile who has no place, no horizon. A society that excludes them only amplifies the dilemma. Being in exile has also inspired artists and generated humanity in people individually or collectively.

I am very aware of the structural damage of exclusion that is part of the ‘privilege’ of being a citizen, an insider, belonging vs exiled, distrusted, outsider. The parallel in my experience is the baby attaching to his family, a journey all of us make and most of us have a good enough experience and survive or prosper. Some of the babies do not do well. Winnicott would say we do not seek ideal, we seek good enough conditions, positive possibilities, creative, caring and laughing at our life predicaments.

Place is a secure base, it is holding harbor, it’s the horizon, the ground, the caretaker or parent’s lap, it is the lover’s arms, it is finding a country that will take you and keep you, if you are a refugee.

Interviewer: Did you paint before medical school?

JG: Yes always, I wanted to study medicine from a very early age. But by the time I arrived at that part of the journey, a part of me wanted to be an artist and didn’t want to go to medical school as passionately as I had held that goal earlier. I had a privilege of coming away from my roots and studying in Montreal but at that stage of life other things had awoken in me. I was divided between ‘painter’ or ‘healer’ identities, I was in retrospect always divided between divergent paths, divergent cultural realities and had to transform those choices to go forward. It seems I have devoted much of my time to medicine and much less to painting, so I suppose both are essential to my work. I needed to paint and I am privileged to have work as a healer. In retrospect I see how the formation of my artist self was stifled by and struggled with the messages I received on what a woman especially a woman of my origins could be or not be.

When my father died suddenly (my first year of medical studies at McGill), it was really a painful turning point. He died as I was seriously contemplating leaving medicine in order to paint full time. But right after his death I felt I owed my father the promise I made him to complete what I had started. So I had to finish medicine. At the same time, I attended night classes at the Museum of Fine Arts in Montreal. There were many adventures along the way. Lismer and David Sorensen were amongst the artists there, though I never had classes with either of them. I learned film and animation mostly, took many life drawing classes there and print making with Pat Martin Bates in Victoria on summer breaks. Meeting painters and people who had other creative lives was part of the excitement of that period of life, walking new adventures was such a wonderful experience at that point in Montreal.

Interviewer: Do your colleagues at the hospital know about this double life of yours?

JG: Only a few are interested in that part of me, maybe it is a more private part of myself. When I have had shows, they are usually announced to colleagues but these shows have not always been in the city where I work. Some exhibits have been in India, UK or Victoria, BC, so not everyone is aware of that side of me. Some of my closer friends now have me doing book covers or illustrating, which I have enjoyed. Many physicians or other professionals have private time where they might make music or paintings or pursue some kind of hermetic activity including running or numerous other activities to somehow rebalance and recover from the demands of the jobs they do. Painting just happens to be a part of a vital part of my life.

Interviewer: Why call your most recent solo exhibition Exile and Attachment?

JG: These are the core issues of relationship, in my life and in the life of many of the families, children and refugees I treat in Montreal.

My father was a refugee in all senses of the word, an unhappy nostalgia and celebration of his lost country, his lost mother, building a marriage in a new world and his finding himself between that old traditional world and actively building a Canadian life, investing in it intensely. Even the letters that would come from India in Urdu took him away to another place and music and language, it was as though he belonged somewhere else when those letters from his mother would come. So who was in ‘exile’ and who was ‘attached’…

So the attachment and exile issues were always deep and present. They are part of living and recreating healthy conditions to live in community. They were evident in how the First Nations and other visible minorities were excluded or ambivalently held in the social space. I was aware of how our community had become a kind of ghetto in places like Paldi on Vancouver Island, it was always part of shaping my gaze and comprehending the gaze upon and from my community. Attachment and belonging are the healer agendas that are the counterpoint — it deals with that which can never come back, that is left behind forever. It can be there in nostalgia or phantasy or imagination but it is not in the Real pragmatic present where we live and move towards the future. The journey is about surviving irretrievable lost good things without losing hope and the capacity to invest in now. How does memory shape us, move us forward to make sacrifices for our children, to live as joyously as we can? Not everyone is resilient, not everyone succeeds brilliantly, but all sorts of things help us along the way to cope and move along our time line in a goodenough way. Hopeful and pursuing the essence of being in the world.

Interviewer: What has exile and attachment meant in your own life?

JG: Many nodal points of my life are about loss and dislocation. Changes in the theatre of life are about where and when and who. Defining who belongs or my not belonging at all. Or trying to make sense of this from my parents, grandparents or close people, the communities around me: it is an over-determined preoccupation perhaps. A neurotic center maybe, or an endless unfinished internal work.

Alienation, nostalgia, melancholy: are realities in my life cycle.

Perhaps the past haunted both my grandparents (largely silent on those worlds) and my parents. I was impressed with those life lessons, somehow implicated in all of it and unable to find meaning just in contemporary or momentary life experience. I realized later that these experiences marked me deeply and have attuned me to the issues of departure and closeness, of migration and belonging, understanding histories and narratives. These became central themes in my life work. I also see that many of my peers did not struggle with these questions in the same way, they had other solutions and made other decisions about these issues. We can all see exactly the same scenario in a community or family and experience differently. This is fortunate and fascinating.

It may be that making meaning and putting pieces together is part of that process for me as an artist: making collages, paintings, irrelevant or constant note-taking perhaps is part of the constant need to be drawing. I have recognized that I have also put myself in exile many times without recognizing it, and later come to realize what I had been doing. It is part of the wisdom of seeing or reflecting later patterns I struggle with and there they are in the series.

I felt the absence of mentors in that earlier time in my life, recognizing now important it is to support children and young people. I have learned to shift to seeking connection and building teams. I have held many memories of failures in my own life, rather deeply felt attachments and exiles.

Interviewer: Where were you born?

JG: Duncan on Vancouver Island. It is not a place I think of without great ambivalence. It seems to me it was a village that was struggling with the death of the Empire and post-colonial resonances as well as the refreshing newness that part of being a Canadian in that time. I was well aware of the racist underpinings towards the First Nations and Asians, and the upper elite was pervaded by British class strata. Now Duncan has changed and the Cowichan valley is some kind of sought after retreat. But when I visit or see Paldi or the debilitated state of Lake Cowichan, I see the old histories are still in the place. I walk amongst the ghosts of that former time. Though it has changed in many ways, I am fortunate that life took us away from there.

My mother was also born in Duncan at the King’s Daughter Hospital. At that point we couldn’t be citizens until after my birth and the Partition of India when Canada finalized its citizenship act. Sikhs were part of the British empire units in the war, but Duncan didn’t recognize this history; we were just people who labored, did mill work, even though some of the lumber mill owners became millionaires, initially we were with the Chinese and First Nations all quite outside of the white society. At the same time the social space was getting friendly with Asian children mixing in friendship and going to school. There was a metamorphosis that has come to be a more inclusive society than Quebec is today.

I was never in Duncan long as an infant before we moved to a mill area outside of Lake Cowichan. We lived in a very isolated place my mother would later tell me about raising her babies where my father had built a mill, then later moving closer to the village, always connected though quite closely to the Sikh community. My second brother was so ill and unwell as a child my parents wanted to move to Victoria for his care. I was then finishing Grade One when we moved to Victoria, a very fortunate move for us I think.

Interviewer: Why do you paint?

JG: It is my healing, it is hermetic place, my temenos, my survival place of retreat, I have to paint. When I finish something that satisfies me, that is a good feeling, then I am back in the world of relationships and family and work.

I recently heard Doris Lessing taking about the neurotic reality of a compulsion to write and I thought of my compulsion to draw and do this making (for her it was a need to write) and then feeling that everything was meaningless or wasted and empty if she had not written for a day: I feel that is closer to the feeling I know or other artists have shared with me may also feel. It is a deeply personal space when one “turns one’s back on the world” to a place with no time, where memory and images come about in the blank. When you are engaged in the making of art, definitely time is different, you are totally engaged. And there is an intense part of the experience that connects with Life yet is not Life. It is making a journey of another kind back and forth in the mind and heart. Like the sound of wind in the trees you must listen for it and it will transform you.

So one has to be careful: literature is not life, and painting is not life. But it a special place that we can visit and it has a special aliveness associated with it.

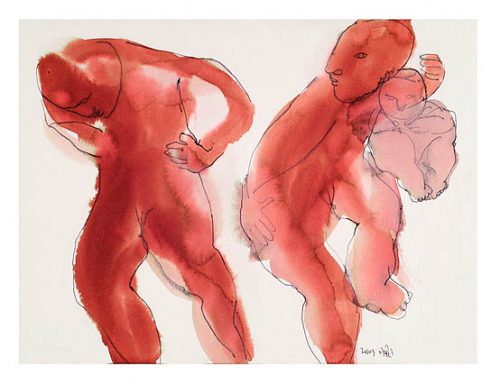

Interviewer: Medium?

JG: For the exhibition series: they are brown, and red only from Ink, walnut tree juice. All the paper is from St. Armand Papier, made by my dear friends Denise and David in Montreal. All that connection to the white ground is not accidental. I love the paper and sometimes store it for a long time before I dare to use it.

Interviewer: Color choice?

JG: Minimal grades: of skin, blood… Occasionally transformation of yellow: new energy

I have very few paintings in that series with a bit of yellow: one is a boy with a bird on his head. And couple dancing together.

The walnut tree juice was from a journalist who was retired and had brought it from his Ontario farm: it was something I loved to use for a many years until if finished.

(Sometimes words are incorporated into my paintings, sometimes prayers, sometimes bits of cloth or other elements: but in this series there are essentially bodies floating in space.)

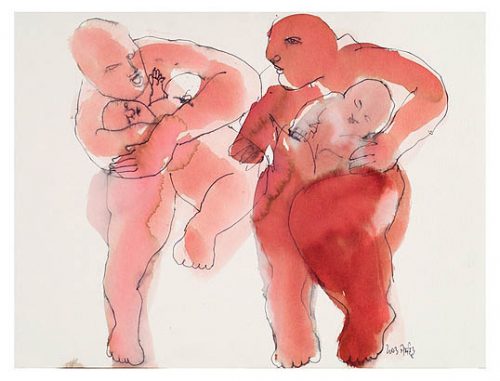

Interviewer: Single body? Two-bodies? Three-bodies?

JG: In relationship of 2 people how many are really present? 3, 4, 9, 15 ? All internal or external or ghosts? How many of us are actually there in a relationship; we are in dyad and slowly we recognize how many are present.

How many have whispered impressions or memories into the ears of the other partner?

So it is hard to know how many are present even in the silence

Interviewer: When no one is around–What does your studio space look like?

JG: On the floor, a mess and left alone it would remain like that, renovation, guests, changes, moving, all of it changes the floor.

Interviewer: For instance, what exactly is the difference between your kitchen and studio?

JG: There is a painting space even on the kitchen table, but the studio is usually a floor space. Usually I spread out the plastic and leave it out to work on the floor.

What does it look like? Depends on the kind of energy, if I am doing many at once and they are all drying or I am able to have the time to get to several at once or to keep reworking pieces. The nature of my clinical work and writing has limited the time I have for long stretches of time for painting or book projects. So often I choose smaller works and smaller paper recently or I make books that have a continuity like free associations do.

Interviewer: Do you paint differently when you are being observed? Or certain works are only created in presence of the ‘other’?

JG: Only certain people can tolerate my drawing or I can feel safe, anonymous or alone enough in their presence to get lost in my pages.

I only recognized lately that some people have felt the act of painting in their presence is like a removal of self and makes them angry and annoyed with me. Other people who have different tolerances or enjoyments of creative making, don’t feel that I am lost as we are accompanying each other, their presence arrives on the page, and in the work too.

Some people in my life have felt I removed myself to paint, from the presence of being together or ‘really listening.’ Though I may have felt I am really listening even communing or and translating experience inner and outer at the same time. And it is a privilege to be able to paint in the presence of others who are comfortable with this activity. It is like a privacy in the presence of a close friend or partner. Usually I am drawing like this in an anonymous space like an airport.

Interviewer: Have you ever destroyed your work?

JG: Often.

My mother threw out all of my work. It took me several years, much later I understood this rage she felt about my hermetic self (reading or drawing). She made it clear that drawing was not a relevant work for a woman especially not a good Indian daughter… unless it was a practical application like sewing. l learned to love sewing from her. She just didn’t understand this space of making art and in many ways I was a disappointment to her as I had appeared to have left the traditional ways though I spent more time in India than any of my siblings.

I also lost and destroyed a great deal my work: for example almost all of what I did on my year off painting and wandering from Point St Charles in Montreal to India. And many other periods of making art were lost.

At times I couldn’t bear to look at much of the work, and would give it away or lose it or trash it. Or make it on fragile paper that fell apart. I think when I discovered Buddhists had prayer papers that would contain the prayers as offering and were meant to be burned, I really appreciated this sentiment of temporary, fragile and gone. Offerings made sense to me. I love working on that paper as it is close to the idea of disappearance. A dear friend would who refused to keep any art would profess to aim for leaving “no traces,” I would say we all leave traces by encountering each other, but art objects are a special kind of left behind object.

It was much later in my art making that I thought using good paper was important. And I started to take more care of the work and put it away before I would be tempted to lose it or destroy it. I think the appreciation of some people who were close to me had valued the work and helped me to stop the repetition of my earlier experience of disappearing or destroying that had marked my earlier efforts. Woman have always struggled with this issue of a room of one’s own as Virginia Woolf called it or find acceptance for having real voice and agency as artists. I am fortunate to have met people on the journey who supported me and validated this healing space.

Interviewer: Who has most influenced your work?

JG: So many artists and friends who are artists and friends: those are important people for me. They were people I talked to at length about what I was doing or they were doing. Or they were friends who simply accepted this part of me and encouraged me, tolerated me or embraced me. They let me play and develop this essential space and activity. And often they didn’t understand why I was so divided between healer and artist.

Paul Klee and Ben Shahn were important when I was in Med School and before.

I saw all the modern Quebec painters. I loved Borduas, for example. I saw wonderful wide range of work especially in Canada, Europe, Japan, NYC and India that shaped me. There is a great joy in seeing the work of children and adults, artists don’t always hang works in galleries.

Interviewer: What makes you move to the next painting and the next?

JG: Like books many at once usually, not able to resolve a problem I might move to another work and then back and forth.

Interviewer: Where do you feel most at home?

JG: With my friends and those with whom I feel safe

Interviewer: Do you feel at home in Montreal?

JG: Yes and no. It is more my home than any other city, I have always come back to it.

It is grande dame, a beautiful city and a familiar place of my formation. So I think I love it in a special way though I don’t think I ever felt I belonged as a Quebecer, I have always felt Montreal was a home to me…so many friendly associations with this city.

I am really estranged from this Quebecois identity, pure laine, separatist, charter agenda and yet I have lived in and found …[some special spaces]… enclaves within the city at McGill and at my hospital. I feel the constant historical tensions wear me down, at the same time they have stimulated my interest in Otherness, in transcultural work, maybe partly even stimulated the need for a hermetic space. The xenophobia that pervades the Quebec identity quest is sometimes distressing and familiar from my childhood, though I realize it is a felt as positive shaping and a search to have ownership of votre pays amongst those who identify with the Quebec nation. For me it is echoes of colonial resonances, not postcolonial reality, lately the support of the Charter renders a kind of latent violence to my sacred rights as a citizen and to minorities in general_ in time of globalization, positive connections are possible across histories and identities, it seems for minorities an undermine of that spirit and the vibrancy of the metropole of Montreal which is not the reality of the rest of Quebec. We have been there before.. I was here when the FLQ was blowing up mailboxes and kidnapped key symbolic antagonists to separatist ideals while I was at McGill as a student. These tensions are ever present and they are now part of a structural exclusion that we accept to promote French nationalism within this province. We are hoping it will satisfy most, if not all of the angst, that is historically embedded as bitter humiliations at the hands of the symbolic British and the Catholic Church. I understand the process but don’t feel any identification with it. It is hard enough to adapt as a visible minority and a South Asian woman and find my way without inviting more tension of ethnic nationalism. At the same time, I have had wonderful friendships here, wonderful colleagues and good working relationships, which I am reluctant to abandon, parts of my family are here and I don’t want to leave.

I am ambivalent about leaving. Being driven out doesn’t appeal to me either.

But it may come to no choice if things are to be so split and divisive for minorities. I have to move in and out of the space to tolerate it so I do global health work in India and Jamaica or other places when invited. What would happen if I did not have the health to move I wonder…

Interviewer: Is Fanon meaningful to you?

JG: Deeply.

I read him in the 1960’s and that was a time when I understood I was identifying with ‘black’ or outsider Quebecers and a black minority, certainly not with the privilege of a European facing Quebec. Much clearer to me that visible minorities were marked just like Hindu castes are marked in your soul as an immigrant Other. I found it exciting to hear Fanon talk about the internalization of these experiences, the mirroring issues of Others amongst the host society, the sorting out of ‘healer’ and ‘victim’, a calm celebration of being safe is part of feeling fortunate to be in Canada and Quebec.

I had many conversations with the Quebec filmmaker Jean Claude Lauzon about his deep love for a Quebec, nonetheless the strong collective of mon pays , the need to belong, forced him earlier in his life to renounce and hide his Abenaki heritage to be embraced as Quebecois..he would not meet me to talk in public space as he was apprehensive about being seen with a brown woman. This is the tension I always feel in the Quebecois identity dialogue. When the collective mood ambivalently embraces or denigrates bits of us, it has a profound impact on what is collectively forgotten or celebrated, what parts of us are safely shown, what parts of us remain private or hidden in order to wander safely in the public space. Artists don’t conform to those rules when they create even if their work might be censored in the public space or misunderstood. Fanon’s thinking addressed all these issues, when he spoke of identity, what affects the idea about African or Others created in psychic imagination can all sorts of dimensions. His writings were never part of any curriculum in my training as a psychoanalyst or a psychiatrist.

These are not resolved issues for me, I see them as dynamic, part of a positive inclusive social space, a real process in Canadian not just Quebec society, not just far away in ‘primitive’ or ‘third world’ spaces. Fortunately in this democracy we are in healthier circumstances than those my parents or grandparents survived. It’s again about a sense of gratitude. I am so fortunate to have options I have had, to work with the people I now work with, and have the friendships around me here or there to sustain hopeful and joyous times.

Fanon was a major thinker like Edward Said as an influence. Later I thought psychoanalysis would be a tool to unravel this, but I was very disappointed in the psychoanalytic group though until I found colleagues amongst them who were receptive to thinking of cross cultural influences like Salman. Other scholars I met taught me other ideas, increasingly I learned that outside histories and political realities were constantly changing how one was constructed. We all move with the currents, changing times on what is or was denied or embraced by the collective. I feel my beginnings in British Columbia and later my visiting relationships with Montreal, Istanbul, London, New York and Mumbai, in particular, were and are cities and spaces that taught me levels of what Fanon spoke of.. but it was my friendships with people who had travelled this common ground and writers who shared that common experience, that helped me the most to see the challenge and growth, always learning about our personal myth making including stories I told myself, and looking at formations that might be possible in a future. Fanon helped to lay out some of the emotional forces that present themselves between alternate collective identities as part of a post colonial world physician. Individual identities do not operate in the same way as collectives do. Post slavery societies in the Caribbean or the diversity of India or Turkey and other places I visit for work, have taught me to absorb other historical possibilities and lessons related to Fanon’s questions. By listening to their identity journeys I could make some sense of Fanon’s questions. It seems to me these issues implicate all of us. Race was only part of the issue he opened for me, there were all sorts of levels of stigma and histories that he helped me to think about. Life is about hybridities for me, working with imaginations, histories and realities together as complex dimensions, the need for a homogenous Quebec or their version of France’s pursuit of ‘laicite’. While I personally have not felt comfortable with belonging to a tribe or group that marks the scope of my imagination or possibilities, I certainly defend the right of anyone to chose their imaginative vista or identity without imposing their myths on others..is that a floating world?

Interviewer: What would he [Fanon] say about this time of this place?

JG: The psychic wounds of history are deep and difficult to treat but people like Mandela have modeled a way forward if we look behind idealizations. Collective denial of racism is still a great challenge to us everywhere, even here in the privilege of Canada we have to struggle with reflection and expanding our discourse.

The recent discussion on the Charter in Quebec has motivated in part the offering of these paintings at this time. I would have left them in the cupboard, unbroken as a series– but sometimes provoking discourse is more important that remaining silent.

It is frightening to hear the silence of the Quebec intellectuals, who frame the humiliation of minorities a cost of preservation of their dignity and legacy, and to hear the capitulation of some provincial liberals. I was moved to see recently the bravery of the former Bloc MP Maria Mourani who has shared her view that protection of human rights for minorities is more securely provided in the Canada than in the spirit of a ‘homogenous’ provincial identity. Well it is just a beginning of another identity passage if governments can proposal in all seriousness even as a political strategy that those wearing kippas, turbans and headscarfs are not allowed to serve as physicians, teachers or public servants. We all hope for a civilized dialogue, and I am amongst those who hope for an inclusive society. What would Fanon say about such a privileged group denying racism or exclusion and asserting that this is a form of enlightenment , I don’t know. I am more interested in what will heal the space, what will bring us together and make the space safer. If human rights agendas can’t override the agenda of Quebecois nationalism then the collective space has to process the implications.

Interesting times.

Interviewer: Where are you headed next?

JG: To more space in my life in good health, to heal and to do more creative work.

I don’t know where or when. I have internal wounds yet to heal and giving time to others is one of the endless journeys that helps that process and personal survival. Don’t know where that will take me, engaged with ideas no doubt but also with the predicament of children everywhere and possibly centered in making paintings.