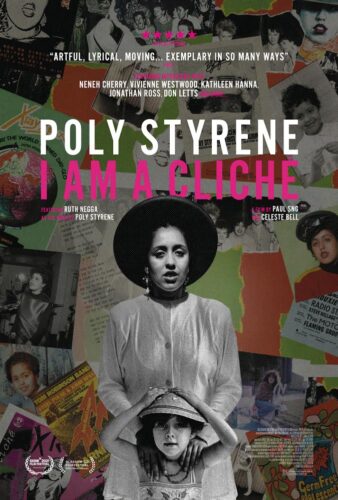

I am a Cliché was released in January 2021 and has been playing mostly through streaming outlets and festivals since the summer. The film gives a rare glimpse into the soul of Marianne Elliot Said aka Poly Styrene, the brilliant, iconoclastic frontwoman for British punk band X-Ray Spex. It’s a sensitive and compelling piece co-directed by her daughter, Celeste Bell, and Paul Sng.

Bell explores her mother’s journey through the challenges that confronted her as a biracial, non-conformist artist, celebrating her life and her art and offering inspiration to future generations of artists. Other than two LPs with X-Ray Spex and a couple of solo albums, very little information remains about Poly Styrene, in contrast to the volumes of material available on her white male contemporaries (such as the Sex Pistols’ John Lydon). This film is a precious document that counters the ongoing erasure of BIPOC presence in the arts.

In addition to the documentary aspect of the film, Bell very deftly constructs a narrative that weaves in the complex and sometimes difficult relationship that she had with her mother, “A punk rock icon,” a famous figure, far removed from the flesh-and-blood person that she knew.

July 3, 1976 was the fateful day when Marianne Elliot Said started on the path to become Poly Styrene. She was hanging out on Hastings Pier on the day of her 19th birthday. She saw the Sex Pistols perform live for the first time. It was a life-changing moment. After a year hitchhiking across Britain seeking a purpose, she collided with it on her birthday!

This documentary may not have happened if Celeste Bell hadn’t explored her mother’s archives. It took Bell five years to process the loss of her mother. When she opened up those archives, she found photos, lyrics, albums… a variety of things of great value and cultural importance. She says she was “blown away” by the quality of her mother’s artistry. She wrote the songs and did all the artwork for the band herself. A number of Poly Styrene’s peers are interviewed in the film and there is broad consensus that she was one of the leading exponents of punk rock and certainly one of the most interesting and gifted songwriters to surface from the new wave.

Neneh Cherry relates how “… the first time I heard Poly’s voice, it was like an awakening for me. There were a lot of men around, but obviously, being a woman and being a young woman, I think Poly being a woman of colour on that scene was another reason why she became a huge role model for me, and I actually started singing because of her, to be perfectly honest.”

Marianne Elliot Said chose “Poly Styrene” as her stage name by looking through the Yellow Pages. “I thought I would use the name of something around today. You know, something plastic and synthetic – and I just looked in the yellow pages and then I saw it. It sounded alright, it was a send-up of being a pop star. Like a little figure, not me – Poly Styrene, just plastic, disposable.

That’s what pop stars sort of meant to me, so therefore I thought I might as well send it up.”

The film takes us through Poly Styrene’s childhood growing up in a poor family in the Gosling Way estate flats in post-war London. There was no separate bathroom and the flat was heated with two coal fireplaces. Her single mother, Joan, or ‘nannie’ as Marianne Elliot Said and her sister called her, worked full-time as a legal secretary.

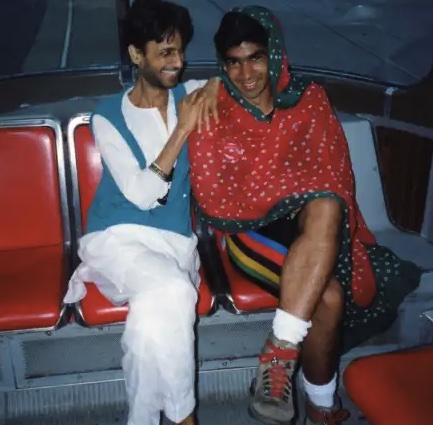

Joan had met Poly’s father at a dance. He was a handsome and dapper Somalian immigrant with impeccable style. He asked her to dance, sweeping her off her feet. Poly’s sister recounts how their mother ended up with no friends: “They saw her as a black man’s whore. It was bad enough being a single mother but being a mother with half-black children was hey hey! The white community really shunned ‘nannie.’”

Poly Styrene struggled with her status as a “half-caste,” fitting in with neither the white kids nor the black ones: “When a white person looks at a mixed-race child, they think, My God, a white person went with a black person or vice versa. It’s their genes really. They want to preserve themselves. Because they see us as a threat to their genetic existence.”

Poly recognized the importance of identity early on. Although a born and bred Londoner, she was constantly questioned about where she was from. She developed a yearning for Africa and daydreamed about running away from England, where she never felt at home: “I wanna go back to Africa, learn about my heritage and how my ancestors lived. ’Cause all I’ve seen is Jungle Book. And I know that ain’t the way it looks. I grew up on Tarzan too. What can you do? I’m going to cross Ethiopia, see that ancient land, and then I’ll go to Somalia, barefoot across the sand.”

She found no role models in the media or in the music business. There were no Black women to be seen on the front pages of fashion magazines of the day. She was one of a handful of women of colour working in an industry full of white middle-class men. So she felt that it was up to her to carve out her own identity.

Poly Styrene was very much into the DIY ethic that characterized early British punk culture. She made her own clothes, wrote her own songs and came up with the artwork for her albums herself: “Clothes are never really you. That’s why people wear them. Cause you can just create an image with clothes. They’re just part of the facade. Which is good fun to play with sometimes.” She placed an ad in the Melody Maker in 1976 that said: “Young punx who want to stick it together.” She auditioned the band members herself, and X-Ray Spex was born.

Rhoda Dakar (The Body Snatchers/The Specials) recalls the explosion of punk rock in the 1970s in Britain: “We were embraced by punk because punk was full of people who nobody else wanted. We were welcomed because we were already outsiders.”

“Some people think little girls should be seen and not heard,

but I think: Oh bondage, up yours!”

~ Poly Styrene – “Bondage Up Yours”

“Bondage Up Yours!” was a call to arms against oppression for women and young people of colour in Britain. The song was rejected for radio and television because of the superficially BDSM theme of the lyrics: “I was just talking about all forms of bondage, you know, oppression and everything else. Sexual bondage stems from that… it’s all part of the same thing really. It all depends which way you take it… yeah, it’s to do with all bondage. And it’s bondage because it hasn’t been played, and that proves it as well. That’s bondage in itself.”

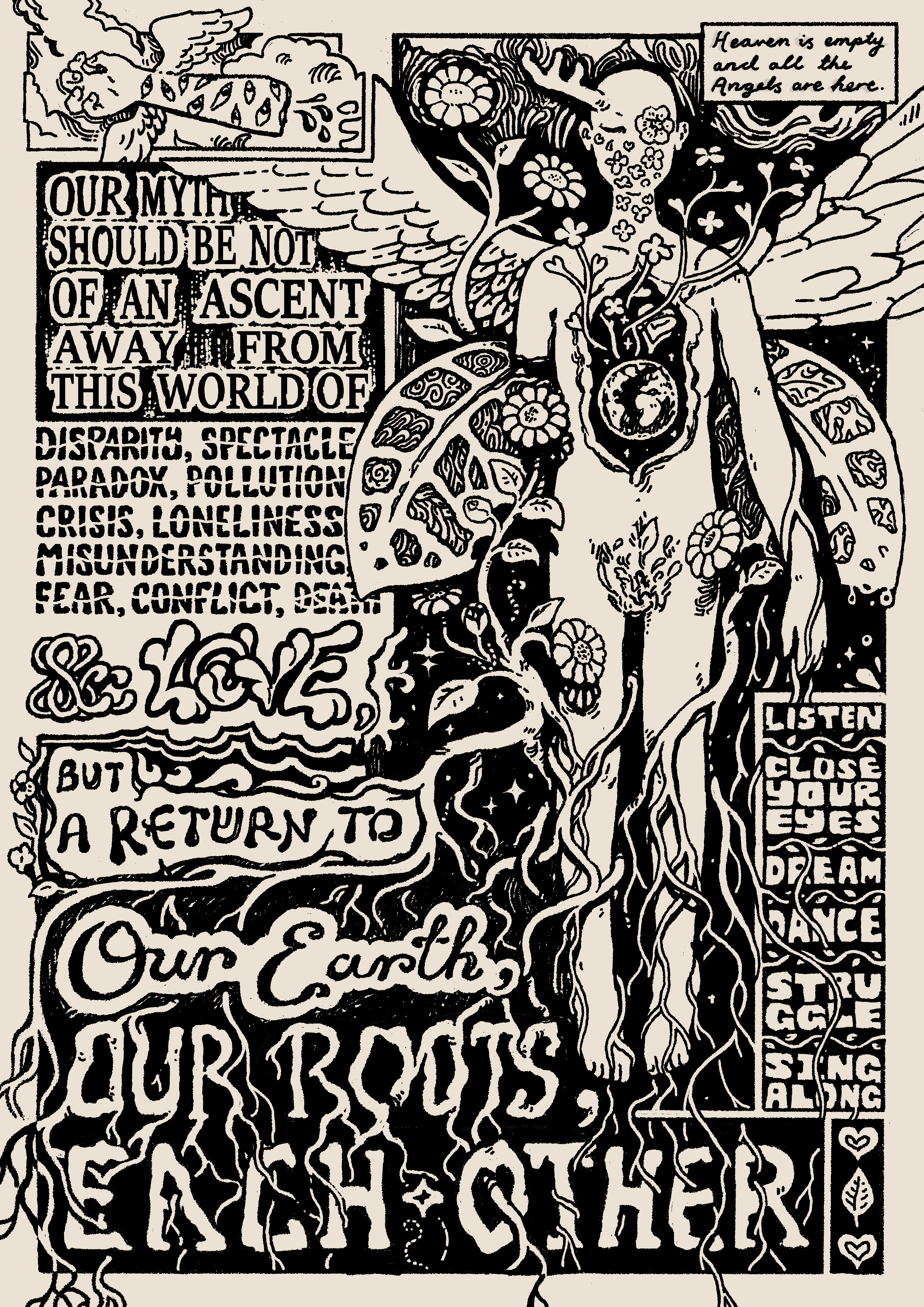

Poly Styrene explored themes in her music that were far from the typical punk rock fare, including genetic engineering, mass media control, the environment, disposable fashion, and society’s obsession with cleanliness. The artifice of the music industry and its insincerity influenced her, and she imagined a future dystopic plastic synthetic universe where the natural world has retreated. The final triumph of everything that’s fake.

Another theme that runs through much of Poly Styrene’s work is that of consumerism. “It wasn’t a conscious attempt to be clever. I just thought that I’d write about all these plastic things because they seemed to be creeping in more and more. Which is why New York totally blew me apart. I saw everything that I’d been writing about in extreme, but for real. For them it wasn’t a joke, it was the way they lived. For me it was all a joke – play with it, indulge it, have fun with it because there’s not really that much of that over here… but when you go there, it’s so bad that you think, God if that’s what it’s going to be like, I don’t want it.”

Over time, her songs were evolving to reflect how her feelings were changing; she wanted to reflect those changes in her music. She had started to branch out of the political power pop of X-Ray Spex, fusing pop, rock, funk and reggae into a rich and at times playful tapestry of sounds that only a rapidly maturing artist like herself could pull off.

She was misunderstood by the media, which wanted more of the original X-Ray Spex brashness. Poly Styrene had already moved on. A diary entry from the time reads: “I muse over the future and all it may bring. I open Pandora’s box of hope. I envision a time in the distant future when synthetics rule. The downside is, humankind will destroy the natural environment; the upside, burgers will be cruelty-free veggie rubber buns.”

Unfortunately, her solo album Translucence, which featured her outspoken political views but showed a more vulnerable and introspective side of her, was a commercial flop that led her to leave the music scene in spite of her optimism.

By the time Bell was born, Poly had left her punk phase far behind. She never really considered herself a punk, nor was she limited by the formula of punk. However, she recognized that the scene was the perfect vehicle for her own creative transformation.

The latter part of the film deals with Poly’s disenchantment with her life as a punk/pop star and the decline in her health. She is confined after a misdiagnosis of schizophrenia. A later evaluation confirms that she was actually suffering from bipolar disorder. After withdrawing from public life, she found happiness and spiritual growth in the Hare Krishna movement, taking her daughter to live with her for a while at Bhaktivedanta Manor in Watford.

Sadly, cancer took Poly Styrene from us in 2011. She leaves a long legacy of accomplishments, including a memorable performance in 1978 at the Rock Against Racism rallies in Victoria Park, London, triggered by Eric Clapton’s drunken outburst in which he praised Enoch Powell’s anti-immigrant philosophies and called for Britain to remain “white.”

Her legacy includes two superlative and hugely inspiring albums with X-Ray Spex, Germfree Adolescents (1978) and Conscious Consumer (1995); her solo albums, Translucence (1980) and Flower Aeroplane (2004); and her final album, Generation Indigo (2011).