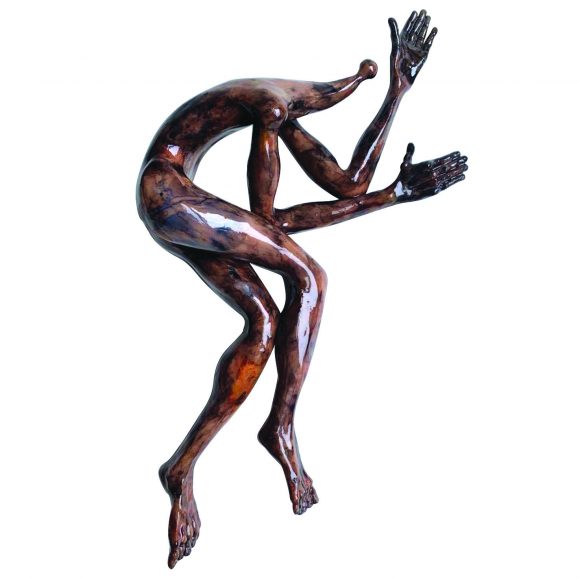

Gavin Morais’ quixotic figures at first seem to harken homologues of his lithe physical outer shell in this world—strange, stretched-out, thin figures twisting, pleasuring, labouring, and always either reaching out or encroaching inwards—all, it would seem, with the intention of searching for some sidereal star.

Gavin Morais’ quixotic figures at first seem to harken homologues of his lithe physical outer shell in this world—strange, stretched-out, thin figures twisting, pleasuring, labouring, and always either reaching out or encroaching inwards—all, it would seem, with the intention of searching for some sidereal star.

At the heart of his figures is, yes, the literal “corpus”—the body stretched into and out of itself, reminiscent of early modern representations of the human body and its inner circuit of skeletal, muscular, vascular, circulatory and abdominal organs. They call to mind artists like Andreas Vesalius in his book Humani Corporis Fabrica Libiri Septem, published in 1543.

Yet Morais, unlike those earlier illustrators of our inner circuitry, seems to be exposing not just an inside of a corpus (with its spleen and entrails) but a more literal assemblage concomitant with the body’s nervous system. In this sense, looking at Morais’ world of twisted figures strewn almost into and out of their own viscera—anonymous lone figures withering, crouching in, or extending outwards—we see the literal affective sensibility of a body that represents some opaque ontological realm. Here, in sculpting his homologue, Morais doesn’t simply sculpt his body or a body—in many senses, the body as displayed seems itself to be the seat of the soul and not vice versa.

The son of a performance poet and nephew of a reputed photographer who worked with Ansel Adams, Morais (a self-trained artist) seems to have turned this sculpting of the world of a particular denizen into something larger than the outside shell we are looking at. Necessarily existential and with glaring allusions to the world of his own ontology, Morais’ figures evidently are simply trying to show us what they are showing us.

Reaching, bending, figuring the manifold ways to occupy space, each of Morais’ beings would seem to be just a figure experimenting with his/her own volume, experimenting with physical space. Yet with his figures’ search for just the right way of occupying space comes the realization that we are necessarily reaching below the particular realm we occupy, to see and grasp some other ineffable realm right here in this one.

Starting with clay to construct these rudimentary figures, Morais is drawn to imbue them with the raw life they must necessarily embody, as though at once reflecting quick shimmering moments of the desperado and at once patiently and devoutly posed as intemporal ascetics. Adding watercolour and rubbing in the colours until the spectrum becomes twisted, then sheathing them with the amniotic viscosity of shellac, Morais eventually gives birth to latent characters that must have always occupied his world.

Like Alberto Giacometti’s leaning and standing primordial figures, Morais’ primordial figures seem to reach back even further in their quest to find an original form of their own bodies and of the world they appear to be searching in.

Like Alberto Giacometti’s leaning and standing primordial figures, Morais’ primordial figures seem to reach back even further in their quest to find an original form of their own bodies and of the world they appear to be searching in.

In this sense Morais’ figures occupy several worlds, being both his homologues and primordial figures to which no identity can be ascribed. At the same time, these figures are so struck in their experimenting with the volumetric aspect of space that they appear to be piercing into something else while seemingly dormant and introverted. Instead, what we might suggest is that his figures are contemplators assuming new ways to arrange the body as they think and ruminate.

A closer look at the figures draws us into an almost uncanny valley, glimpsing something from our world, something from a nether world, and something we might see in the future as a future past body. If Morais is seeking anything, it is to find new ways for us to inhabit the space and time we live in, and—beyond the corporeal body—new ways to delve into researching other forms of “existences” we might have passed through or might come into in the future. Strange alien mobile figures—we feel like we have seen them before but they are so deeply immersed in the world they occupy that the only thing we can do is sit back and ruminate on them and with them, as they ruminate on something we just have not yet seen.

All sculpture and photographs © Gavin Morais