Feast time for poetry

In the 70s, Perú was blooming with all sort of audacious ideas, from feminism to social rebellion and sexual liberation. It was feast time for poetry.

Hora Zero was a group of talented, insolent poets who erupted on the scene in full confrontation with the poetical canon. (The only poet who escaped their attacks was César Vallejo, who was already “the avantgarde of the avantgarde,” both in his poetics and in his ideas.)

The group’s poetry proposed a new approach, closer to the everyday life of people who lived on the margins of power, which was to say, most citizens. (Things have not changed much since then, as anyone can see in the news.)

Enrique Verástegui was one of the founding members of Hora Zero, along with Jorge Pimentel, Juan Ramírez Ruiz, Carmen Ollé, Tulio Mora and several others. Verástegui, a narrator, philosopher, essayist and mathematician, was of African and Chinese descent. He was married to Carmen Ollé, another important poet, who was well known as the author of Noches de Adrenalina.

At the age of 21, Verástegui published En los extramuros del mundo, one of the most iconic books of the movement, with verses such as these:

Grito, llamo, me desgarro. Pero nadie acude a mi lado.

Nadie posee ese don de ser para mí una tinaja con agua de lluvia: una tinaja de palabras que estallen

como una molotov en los muslos de la poesía.

[I scream, I call out, I tear myself apart. But no one comes to my side.

No one has that gift of being a vessel of rainwater for me: a vessel of words that explode

like a Molotov on the thighs of poetry. – Serai’s translation*]

In 1975 Enrique Verástegui recorded his poems for the Library of Congress, and the following year he won a Guggenheim Fellowship that allowed him to travel to Europe, where he studied Sociology of Literature at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales. Around that time, he was selected to represent Latin America in a tribute to Allen Ginsberg at the Residence for American Students and Artists, also in Paris.

In the preface to Angelus novus I (one of the books of the Splendor pentalogy), the critic Ricardo Gonzáles Vigil comments: “It burns, transports, transfigures, sets fire to, embraces, conjures, opens, totalizes, dresses and undresses us. […] His writing is excessive, virtuous, unleashed, intellectualist, muddied by life. In Verástegui’s work we can hear a generation of advanced Latin American poets, in tune with the poetics that made radicality a standard for the new disorders of world systems.” Such depictions certainly describe poems like “Si te quedas en mi país,” which starts off like this:

If you stay in my country

In my country poetry barks sweats urine and its armpits are dirty. Poetry haunts brothels it writes songs whistles dances while gazing idly in the bathroom and has known the sweet taste of love in coy little parks under the moon of the street vendors’ carts… [Serai’s translation*]

Si te quedas en mi país

En mi país la poesía ladra suda orina tiene sucias las axilas. La poesía frecuenta los burdeles escribe cantos silba danza mientras se mira ociosamente en la toilette y ha conocido el sabor dulzón del amor en los parquecitos de crepé bajo la luna de los mostradores. Pero en mi país hay quienes hablan con su botella de vino sobre la pared azulada. Y la poesía rueda contigo de la mano por estos mismos lugares que no son los lugares para filmar una canción destrozada. Y por la poesía en mi país si no hablaste como esto te obligan a salir en mi país no hay donde ir pero tienes que ir saliendo como el acné en el cascarón rosado. Y esto te urge más que una palabra perfecta. En mi país la poesía te habla como un labio inquietante al oído te aleja de tu cuna culeca te filma tu paisaje de Herodes y la brisa remece tus sueños —la brisa helada de un ventilador. Porque una lengua hablará por tu lengua. Y otra mano guiará a tu mano si te quedas en mi país.

Memories of a groupie

Hora Zero encouraged the revival of poetry and of the arts all over Perú. Its members stimulated the creative juices of a whole generation, including our small filmmaking collective, which had at least one point in common with them, the irreverence of our name: Grupo de cine Liberación Sin Rodeos, “liberation without beating around the bush.” The name irked the right, of course, but also the more traditional left, which did not take sarcasm lightly.

We were Hora Zero groupies, so when Enrique told me about the cimarrones, African rebels who escaped the haciendas to live in freedom, he caught my attention. Coastal Peruvians were very aware of the huge influence that Afro-Peruvian culture had had on literature, music and customs, but the rebels’ story was not very well known.

Enrique kept telling me about the cimarrones’ way of life until one day he said what I was hoping he would say: “you should make a film about this.” Shortly after that, I received a small inheritance and, guided by Enrique, we started doing research at the National Library, where we found abundant material to nourish our simple script. Enrique Verástegui and his family lived in Cañete, a coastal town very close to the harbour where the enslaved people had been brought. To this day the region has an important concentration of Afro-Peruvians. Armed with a lot more enthusiasm than money, our small team of filmmakers set up camp in a room given to us by the local agricultural cooperative.

We started location scouting and looking for natural actors.

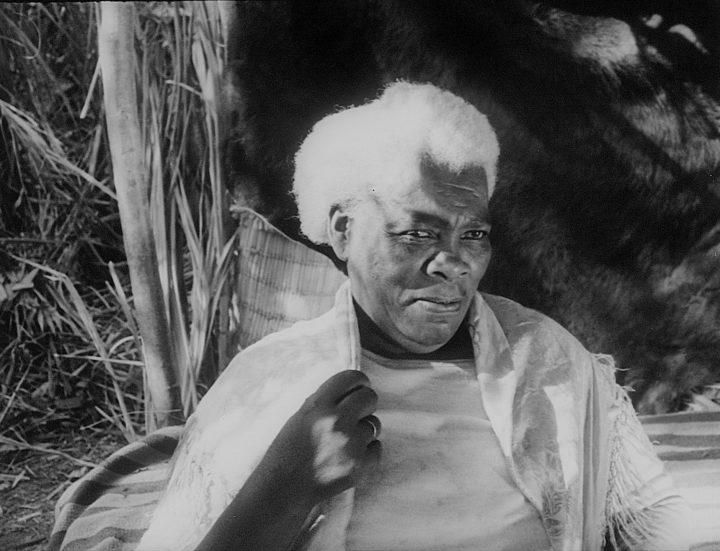

I found the “older rebel” while driving around the Cañete area. He was riding a heavily-loaded tricycle on the highway when I saw his face in the rearview mirror. I waited for him by the side of the road to tell him about our film. Would he like to join us as an actor? He replied that he had never been to the movies, but that it sounded interesting. But first he had to find someone to replace him for a few days; the pigs he fed by collecting the trash he had in the tricycle were hungry day and night.

He caught on quickly and on the second day of filming he started giving me advice, suggesting camera positions, in a discreet manner, so I wouldn’t lose face in front of the crew. We soon began calling him Señor Director.

The coup d’état by the rightwing military came soon after we finished the production of Cimarrones and in the rush of exile, I lost track of several actors. Several years later, when I was able to finish the movie at the National film Board of Canada, I had to invent two names for the credits. More than 40 years later, through a group of young people – Colectivo Sur-real – who are committed to celebrating their Afro-Peruvian heritage, we were able to find the actors’ real names: Paulo Lobatón Alvizuri…

…and the Queen of the Palenque, Victoria Pacheco Bernales.

Cimarrones is the first fiction film – and some say the only one – devoted to the early history of Afro-Peruvians. It was shot in Peru in 1975 and completed in Canada in 1982. Because of the precarious social, political and economic situation of the Afro-Peruvian population, the film was ignored until 2020 when the LUM (Lugar de la memoria) showed it on Afro-Peruvian Day. In 24 hours, it was seen by more people than in the previous five decades.

* These excerpts of Enrique Verástegui’s poems were translated into English by Claudia Itzkowich Schnadower.

More on Carlos Ferrand and his work

Interview with Carlos Ferrand (2021), by filmmaker and curator Cecilia Araneda

A small sampling of films (available in several languages)

Americano (110 min., Les Films du Tricycle, Québec, 2007) – Spanish, English, French and Inuktitut

13, a ludodrama about Walter Benjamin (77 min., Les Films de l’Autre, Québec, 2018) – French and English

Jongué, a nomad’s journey (81 min., Les Films de l’Autre, Québec, 2019) – French and English

Photographic works

Series in the permanent collection of Madrid’s Museo Nacional–Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Books:

Cimarrones – SBC Galerie d’art contemporain, Montréal, 2021 (ISBN 978-1-7778841-0-9)

For those interested in the film Cimarrones or the book, please contact Carlos Ferrand: carlosferrand@gmail.com.