[Editorial note: This issue would not be complete without Ian Ferrier’s live performance of his poem, Emma’s Country, at Montréal Serai’s 32nd anniversary celebration on June 21, 2019. A link to that performance can be found below.]

Background to Emma’s Country

Although some of the names and circumstances have changed, a lot of what happens in Emma’s Country did take place. I went out with the daughter of a Gaspé fisherman. Twice we visited her father, who had fought in World War II and been imprisoned in appalling conditions after the fall of Hong Kong.

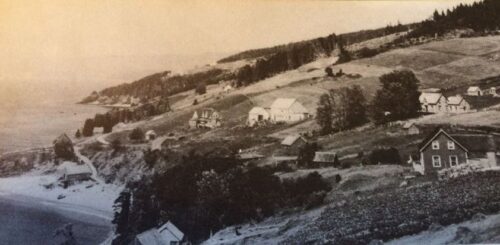

After the war, he returned to fishing and became one of the founders of the Quebec United Fishermen, a group that represented fishermen in their negotiations with wholesalers and fish packing plants. But his life was about to be upended by two other events beyond his control. First his house, indeed his entire village, was expropriated to create Forillon Park at the tip of the Gaspé peninsula. This was a real tragedy, as the amount of compensation given was not enough for any of the villagers to buy property elsewhere. As the village was dismantled, his daughter remembers sitting in her house, now without electricity, and watching as their neighbour’s now empty house was burned down by park authorities. She still experiences the events as the destruction of her home and the scattering of everyone she knew. Her dad and his wife ended up living in his mother’s house in Port Daniel on the Baie de Chaleur.

The second shock was the appearance of massive BC factory trawlers that dragged up every single fish. This practice wiped out the huge banks of capelin, a small fish the cod fed on. With no food, there were hardly any cod, and Gaspé fishermen could no longer make a living. When she and I went to visit him, he was still fishing for lobster in season, jigging for cod, and keeping a small mackerel net strung on a nearby inlet.

I only went out fishing with him once. We awoke in darkness and headed out to sea in a small dory with an outboard motor. Jigging for cod meant throwing a line studded with hooks over the side, jerking the hooks up and down, and then dragging the line back up. He was not impressed with my fishing skills, which returned two small cod and a very ugly fish they called a crapaud. But for a city boy whose job at the time was proofreading for a computer company, pulling fish from the sea was a revelation: a livelihood made in the same way it might have been a thousand or even many thousands of years ago.

On February 14, 2011, the House of Commons made a formal apology to the 325 families whose homes were erased by the expropriation. The Parks Canada site, in an ironic sort of gesture, now grants any of the original inhabitants of the village of Grand Grave, and their descendants, free passes to visit Forillon Park and the site of their old village.

Ian Ferrier at Espace Knox in Notre Dame de Grace, Montréal – June 21, 2019

Emma’s Country

(for Elwood Dow and his daughter)

Crickets sound.

The swish and roar of cars

carries up from the coast road.

But cars are few and far between

and things seem simple in Emma’s country.

Breeze blows cool through the window at night,

circling the forest walls of the attic.

Walls that house the visiting daughter

and her lover aged twenty-two,

Emma whispering hush as the bed creaks

and they hold dead still,

laughing,

shy because her mom and dad

and grandma sleep below.

Since they moved in here

the plant beneath the skylight

cascades wildflowers,

filling the air around the narrow bed

as if it were their fault it bloomed.

And nothing softens the noise in the silent dark,

though in the intervals,

between the words in talking,

behind the sound of crickets

and at the bottom of all hills

the ocean is never still….

Her dad’s a fisherman. Sired three daughters

though even the youngest is six years gone.

Formed the United Fishermen in the ‘50s,

a co-op that still serves this coast

though no fish left, and the cove

a ghost town where his kids were born.

And when they return to that cove

Emma holds her boyfriend’s arm so tight

it’s as if the ground’s crumbled beneath her feet,

as if she were falling

as if her childhood were falling away.

And the long surge of the ocean

tears past Newfoundland,

choking the gulf with saltwater & life,

and Emma the child who played along these beaches

saying “Daddy will you take me out on the boat tonight?”

And he says “Well grab your jacket then. And a lifebelt too.

We’ll take the skiff and see what’s biting tonight!”

And her boyfriend, that was me:

paraded before mom and grandma

and dad who did not say ten words

the first days I was there

before opening a flood of stories,

the copper history of his life

engraved on those nights—World War II

and the fall of Hong Kong,

Japanese jailers

and dysentery starving him to half his weight

before the blast.

And the months before he was shipped home….

And the years waking at 3 AM, and by dawn

far out on the water fishing….

One winter night he walked

thirty miles on snowshoes

Because he could not wait to propose to his

girlfriend, Emma’s most beautiful mom.

There’s a photo I saw, in black & white.

He’s standing on the side of a hill

with Valerie and Emma swinging from his legs

colt-like and pretty,

neither more than waist high to him.

And he—their sole guardian & protector— reaches

one great hand down to each of their shoulders,

palms creased from hauling

two hundred feet of line down and up all day.

He holds them safe against the wind.

The hill slopes down to the sea

and now the wind has come up even stronger,

blowing his hair straight back

and his face weathered as if in bronze.

And she says “Daddy will you take me out on the boat tonight?”

And he says “O no, not this time Emma. It’s too black even now,

and by morning just you watch it blow.”

And isn’t that the night a wave shatters the wheelhouse

and they’re running from the wind

torn from the Gulf,

pitched four hundred miles to the North Atlantic.

Her dad’s gone now. Died starved for oxygen

in hospital in Montreal.

The daughters all have children of their own,

Emma and Valerie’s both in high school….

What is there in a photograph

that the soul and force of a man’s eyes

burn through it even now?

A girl could fall 40 years through time

feel her dad’s hand

rough against her shoulder….

For a thousand years people have fished this coast.

And when we return to that country

Emma holds my arm so tight

It’s as if the ground had shifted beneath her feet,

as if she were falling

as if her childhood had fallen away.

This poem was performed on Ian Ferrier’s CD, What is this Place (Bongobeat Records). It appears in print in his poetry book, Coming & Going (Popolo Press 2014).