Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda wrote a passionate ode to the humble onion, acknowledging its importance as a staple food both for poor and rich. Marie Antoinette showed up her (wilful?) ignorance when she urged her subjects to eat cake instead of the bread they were clamouring for. Sadly, she had to eat humble pie when they sent her to the guillotine for not being in touch with her subjects. No more pie for her, humble or otherwise!

My Belgian mother used to coo “mon chou” when holding me in her lap, perhaps because one of the myths sold to children in Europe was that babies came from cabbages. On rarer occasions she called me “pumpernickel,” which pleased me no end since I love that heavy but nutritious black bread. I have since learned one of the possible origins of its name, which unfortunately involves the word fart. I can only hope it is a spurious etymology.

Riffing on the subject of affectionate or cheeky monikers based on food, Nilambri, Claudia and I came up with some tasty morsels:

Pelos de elote (corn hair) was Claudia’s contribution, as her pale blond hair is the object of frequent comments in a sea of dark-haired Mexicans. Nilambri came up with a spicier version from Indian cuisine: “I am laung (cloves), you are elaichi (cardamom), presumably a man addressing his lover. Not to be left behind, I am reminded of the Mexican song where the man describes himself: “Soy como el chile verde, picante pero sabroso.” (I am like a green chilli, hot but tasty.)

English speakers need not despair. Many terms of endearment involve sweetness, perhaps because England became rich thanks to Caribbean sugar (based on slave labour). Words like “sweetie” and “sweetie pie,” mainly used for children and Barbie-like lovers, are a staple in the Deep South of the US of A. But you don’t have to be a doll to be so addressed. Just try and interact with a shop assistant, regardless of your appearance or age, and you will be called honey without a moment’s hesitation.

Pan (bread) is used to describe a kind man in Spanish-speaking countries, maybe because men were traditionally the breadwinners. Terrón de azúcar (sugar cube) is commonly heard in Spain. I’d better stop here before sounding schmaltzy. You might wonder how that Yiddish word for sentimental first emerged. It comes from the High German schmaltz – rendered chicken (or other animal) fat. By the way, that’s most probably the secret ingredient that cures a cold in mother’s chicken soup.

All this talk of food makes me think of one of my favourite comfort foods, el tamal, or tamale in English, borrowed from the Nahuatl word tamalli. A tamale is a rectangular patty of corn meal stuffed with meat, dried fruits, veggies or cheese and wrapped in a corn husk. In some parts of Mexico and Central America, this staple – which is a delicacy – is wrapped in banana leaves.

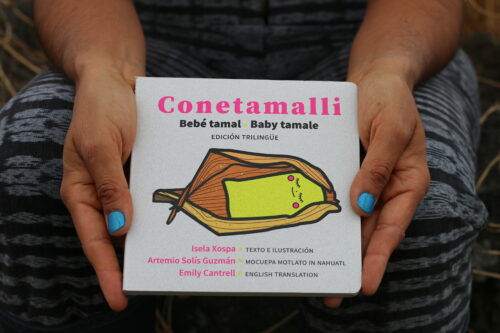

A tamalito, or mini tamale, is also the protagonist of a lovely little children’s book by illustrator and editor Isela Xospa. A popular version of the larger tamale – tiny and endearing in its snug swaddling, irresistible at parties, weddings, christenings and other special occasions – it is hardly surprising that tamalito is the nickname given to babies.

That immediate “kernel” of connection is exactly what Isela explores in her carefully designed and crafted book. Created with recycled cardboard and printed with vegetable ink, the book offers simple yet powerful insights into culinary traditions, illustrating the vital role of independent publishing endeavours and the rich possibilities of multilingualism.[i]

Take a close look at the images and follow the story in Nahuatl, Spanish and English. You will be delighted to learn how to swaddle a baby – or a tamale. You might also be inspired to search for associations between traditional foods and cozy feelings in your own language and culture.

[i] Conetamalli, Bebé tamal, Baby tamale, by Isela Xospa, Xospatronik, Mexico City, 2021. The book received the Mexican government’s award in 2021 for best book in anthropology and history.