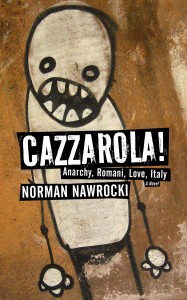

Cazzarola! Anarchy, Romani, Love, Italy: A Novel, Norman Nawrocki, PM Press, 318 pages

Disclosure: I always loved gypsy culture. From Tony Gatlif’s films to his soundtracks and sometimes even the works by non-Romani Balkan filmmakers who examine or exploit Romani culture as subject

In Cazzarola! : Anarchy, Romani, Love, Italy, American tourists are without Old World guile, gawking and taking photographs of a violinist, “real-life gypsy” busker. It is dangerous to romanticize their carefree, soulful music and lifestyle, for obvious Orientalist excursions. You will always be a Gadjo, non-Romani, looking from the outside in.

I started to read Norman Nawrocki’s Cazzarola! Anarchy, Romani, Love, Italy at the same time that media reports about Roma persecutions emerged such as Maria, the blonde child found in a Romani camp in Greece. Maria, who was given to a Romani couple by her impoverished Bulgarian Romani mother, created hysteria about stolen children by gypsies , a well-known stereotype. The story had repercussions elsewhere in Europe where other light-skinned Roma children were taken away from their biological parents by Irish social services. DNA cleared the biological Romani parents in Ireland and the Bulgarian mother confirmed the story and subsequently, all her children were taken from her.

Concurrently, there were reports concerning the prosecution of the Roma people being deported in France by François Hollande’s Socialist Party. This was in continuance of the massive deportation in the thousands, or by the planeload, and the destruction of their camps policy that former President Nicholas Sarkozy commenced in 2009. Furthermore, Manuel Valls, the Minister of the Interior, stated that “Roms refused to integrate”, and that 93% of its citizens polled agreed with his statement, “France was not here to welcome these populations. ” This echoed the former Italian politico, Gianfranco Fini’s “Roms can’t be integrated into our society” years earlier.

Cazzarola! Anarchy, Romani, Love, Italy is a mammoth work with vignettes that are a-chronologically sewn into the multiple narratives. The Discordia family is portrayed throughout the ages, all hailing from the illiterate shepherd from turn of the century Abruzzo. He represents an agricultural society whose semi-educated brothers end up in factories in Milan and Turin, get involved in anarchism, worker occupations of factories that industrialists quell by funding fascism. They play roles in the Resistance to the resurgence of extra-parliamentary radicalism by his descendants. The family is so large that Nawrocki had to draw up a family tree in the preface. The Discordias seem to be everywhere and at every important labour movement and political moment that marked Italy’s history.

From the very onset, Nawrocki paints Italy as a racist place. The novel is set during 2008 when Berlusconi governed with former neo-fascists and the Northern League, and his media controlled the climate to support anti-immigration legislation. The government’s competing ideologies aren’t specified; to a self-proclaimed anarchist like Nawrocki, every government is the same. The newly neo-fascist Roman mayor at the time, Gianni Alemanno, exploited the security card for his election after a naval officer’s wife, Giovanna Reggiani was mugged, raped and killed by a Romani and thrown in a ditch near his camp. Nawrocki doesn’t name all these real-life hate instigating villains (Alemanno, Maroni, Calderoli) except for one mention of Berlusconi and Fini; instead he opts for caricature and composites of these politicians, for example the sexually lecherous, Senator Fancazzista from the Northern Patriot Party ( except that he is from Florence, which isn’t in Northern Italy or even close to their electoral base, Padania).

The novel’s News section, ripped from the headlines, is too real: attacks on immigrants, gay tourists, Romani by mobs, fascist thugs and institutional representatives, brings to life moments we denounced at the time. They sporadically remind readers it is historically situated in 2008.

“News: Italians clap and cheer as police move 300 African immigrants out after clashes with locals…immigrant farm workers shot, beaten and run over…” (pg. 50) This account doesn’t contextualize the first incident involving citrus pickers living in abject poverty in Rosarno, Calabria from the second news item, where nine African immigrants were mowed down, known as the Castelvolturno Massacre, in Caserta by the Camorra. Or, the Senegalese shot in Florence by a neo-Nazi and the shopkeeper and his son for killing an African for stealing junk food in Milan. Name the incident, it’s in there. The two anti-racism demonstrations by immigrants, unions, Italians and Rom activists in Rome are also included. But episodes of Italians’ solidarity with the poor and the displaced are few in-between.

Some of these headlines were government pronouncements that never materialized into law such as former Mayor Alemanno’s promises. “News: City of Rome plans series of ‘fence-in’ Roma ghetto-camps modelled on camps Nazis set up in 1940s in Poland.” Northern League also announced a national identity policies about taking zingari kids out of camps into schools and public housing as an excuse to raze camps, take DNA profiles and pass language test requirement for immigrants applying for permanent residency. This was posturing, since waiting lists for public housing for Italians without political connections are impossibly long.

The worst incidents of Romani persecution were in Turin and Ponticelli, a suburb of Naples, where lynch mobs entered camps and set homes on fire. It was filmed and posted on YouTube, fueled by rumours of a false rape story a teen, told to cover intimate relations with her boyfriend and the rumour of a baby kidnapping, respectively. Nawrocki compares the incivility of a garbage strewn Naples and the mob violence, versus the so-called filthy Rom. Vigilantes that the Northern League called le ronde and other uniformed extreme fascist militias cropped up, wielding clubs and entering camps, firebombing Romanian stores (because racists can’t tell Rom and Romanians apart). The deportations of 100 Roma occurred in 2007 at the same time as Reggiani’s murder.

Nawrocki, in the role of an observer, exposes the internal historical hatreds that divide Italy. If Northerners and Southerners hate each other, it is almost normal that they transfer their hatred onto outsiders. One vignette entitled Common Myths About the Roma, has “two unemployed, hungry labourers from the south of Italy, dark-skinned, stocky … ‘You know what they say about those damn gypsies? That they kidnap children.’ ” The other chap retorts, “Only because the government outlawed them. Blames them for everything. If everyone thinks you’re a criminal because the government says so, then no one wants to work with you. If nobody wants to hire you, how do you feed yourself? Sometimes, you have no choice. Steal or starve. Like our people. Not all of us are crooks, right, but some of us have to eat, too” (pg. 28).

The none-too-subtle condescending joke in the Livorno vignette of Tuscans making fun of Southern terroni is intentional on Nawrocki’s part, to show prejudices are deeply rooted even within Italian people. The description of Ricardo and Carmela, twins studying in Turin, “Southerners, they are olive-skinned with large mussel-black eyes” (pg.192).

At the same time I was reading the novel, Italy had its first black and immigrant minister, by way of an unelected coalition government– Cecile Kyenge, who left Congo, working nightshifts as a chambermaid to pay for university to become an ophthalmologist. That didn’t fare well with racists in many parties and when she announced she would give automatic Italian citizenship to children of immigrants born in Italy, there was a concentrated effort to intimidate her. A Northern League politician calling her an orangutan while burning effigies appeared at her public appearances because her schedule was published daily in their Padania newspaper. Beppe Grillo’s nebulous and populist, Five Stars Movement also rejects this idea that a child could be born Italian from immigrant parents. Hard to disprove Italy isn’t racist, even from left of centre newspapers like La Repubblica’s Facebook page where comments reflect every political colour. Boatloads of refugees, fleeing from Eritrea and Syria, land on the tiny island of Lampedusa while the E.U.’s apathetic lassitude does not allow these refugees into their lands. A glimmer of humanity was restored in Pachino, in Sicily’s mainland, recorded by filmmaker Pasquale Scimeca’s mobile phone, as sunbathers formed a human chain to help Syrian refugees off their dinghy. It is often said, “Italians are better than they appear.”

In Cazzarola!, Italians appear in that very negative light, the onslaught is unrelenting with News headlines and episodes of we don’t serve gypsies to institutional racism by police throughout the novel as vignettes. Almost all Italians are portrayed in a similar vein, with the exception of the Discordia family and their politicized associates, the novel’s only heroes. And they are always present in all those events in the Grand History of twentieth century Italy.

The contemporary member of the family, the love angle in the main narrative, involves an immature Antonio Discordia, who becomes love-struck with a beautiful violinist girl, Cinka Dinicu, a Romani from the outskirts of Rome. The novel does acknowledge that this is highly unusual; seeing that the traditional role of Romani women as housebound mothers in long flowing skirts. Cinka says: “In our culture, women aren’t supposed to play an instrument, only sing and dance.”(pg. 14) Few get an education with the exception of those who run Romani defense groups.

The ‘awesome’-filled banter between Antonio and his anarchic friends, who come from well-to-do families in Rome, loaf about in a band makes the book less successful when the young adults engage in an alcohol-soaked preachy preach, try to enlighten us about global structures and how it affected Italy, the way young adults do. All this transmitted by way of infectious exclamation marks on paper. We assume that the politicized readers of PM Press, who pick the book up, expect didactic material. On the Hot Autumn strikes in 1969/1970: Rafaele, Antonio’s cousin, “Back then, they couldn’t have known that ‘Fortress Europe’ is part of an international mega-new-world-order strategy” (pg. 30). Nawrocki successfully captures the recent Italian penchant for swear words like cazzo peppered in every sentence and era, regardless of the age of the characters. Cazzarola is an expression that can be innocuous in polite company or allude to cazzo which lends itself to other insults, and compound words, with the male sex organ as root.

The Part About Love

The star-crossed lovers begin their romance, with the narrative device of Antonio Discordia observing the prejudice that Cinka and the Romani face on a daily basis. He brings food for her family and advertises her violin skills for his relative’s countryside wedding. Yet, he does not introduce her to his immediate family in her everyday clothes and hasn’t told them about a major life-changing event because “they’re a bit racist” (pg. 293). Cinka stresses about never bringing him to the camp since marrying a gadjo, let alone date one is forbidden. When she does, her mother Luminitsa accepts the relationship which doesn’t mean that the camp’s mores aren’t infringed. The prying eye of the gossiping neighbour relays information back to their camp in Romania since Cinka was betrothed to a fellow Roma, Luca, when they were 14 years old.

The only Romani ever tied to a life of crime in the novel is Nicu, Luca’s cousin, who runs a criminal gang and urges Luca to come to Italy to avenge his name. Now that Cinka is “soiled” and “defiled” because she “didn’t honour the arrangement,” honour killing is pontificated “if she doesn’t want to go” since everyone in town mocks him. When Luca arrives in Rome, he is an ineffectual drunk, lost and alienated, surrounded by materialism he can ill-afford.

Nawrocki captures Rom life since he visited the camps in his own research sojourn. We are privy to the inner sanctum of camp life of Tor di Quinta’s homes made with wood and scrap metal where women need to travel to get potable water for cooking and cleaning needs.

Cinka’s younger brother, Corvu is also a musician, an accordion player. After their father died and when they arrived to Italy, Corvu became the man of the house so he no longer can go to school. He tells his youngest sister Celina to become a doctor or he’ll beat her up, disregarding her desire to be a teacher. Through Corvu, we get the sense how the Romani try not to be too conspicuous in spite of playing, begging and navigating in the Gadjo world. Cinka told him, “Smile, be polite. Don’t give them a reason to pick on you”(pg. 56).

After their first time lovemaking, Cinka tries to explain to Antonio that theirs is an impossible relationship between Rom and Gadjo. When Cinka talks about leaving Italy, Antonio suggests she join anti-racist activists to which Cinka retorts, “My people are activists every day. Active trying to survive. Italians have no idea…One white Italian woman is murdered. And, please understand, I am revolted by this…But one woman is murdered and entire government reacts…Do you know how many Roma have been murdered by vigilantes in Romania and even here? Not once did a government official ever speak about it or denounce it. Not once did anyone demand government action or pass an emergency national decree to arrest or deport the criminals?” (pgs. 175-176) “As if all Italians are angels? And the Mafia doesn’t exist?,” accuses Cinka (pg. 288).

Interesting tidbits in the novel shed light on the history of Romani persecution, the Day of the Rooster, commemorating the day the Turks wanted to kill Romani children – a Romani mother killed a rooster and painted the door with blood to fool Turkish soldiers. The history of Romani persecution in Italy is also documented; asking and receiving passage through Papal lands in 1422 and later expulsed. Holy Roman Emperor Maximillian I decreed burning and killing Romani wasn’t a crime in 1500. That Romani were in slavery in Romania until 1865. Before their expulsion, Mussolini called them subhuman in 1926. But we all know their treatment under General Franco and Hitler’s Final Solution, the porrajmos.

The contemporary storyline where an anarchist named Ox infiltrates neo-fascist groups is gripping. (Who the neo-fascists recruit, how they operate and how the overlords stay out of the dirty work). But, the denouement is left hanging. Cazzarola! could be a primer about militancy in Italy: from the birth of the anarchical movement in Italy to Diaz Schools’ raids and Bolzaneto detention abuses at the G8 Summit in Genoa. Perhaps, it is too much to ask of the diaspora’s second generation to know these events when Italian history is forgotten back in the Motherland, where the average quiz show contestant can’t even guess the fascist decades even with the aid of multiple choice.

Nawrocki already had another novel translated into Italian. If an Italian publisher buys the right to translate this book to educate Italians, they might pause at the spelling such as clandestinos, Giuseppi, Gracia, Ricardo, Rafaele or Alphonso which should be clandestini, Giuseppe, Grazia, Riccardo, Raffaele and Alfonso. Rafaele’s nonna named Consuessa and female activist Agnesia might be poetic license. Luckily, there is a family tree in the preface since there are multiple secondary characters with similar sounding names –Massimo in the 1920 storyline and Massimaxo in the contemporary storyline, two Rafaeles, two Selena and Celina, two Ginos and great-grandfather Antonio like our main character.

Sometimes the narrative is in the point-of-view of the character in the vignette and sometimes the author’s voice overrides the character. Nawrocki performs these characters on stage on his recent tour of Canada as well as performing music he composed for the novel.

Cazzarola! Anarchy, Romani, Love, Italy is a timely and urgent collection of cautionary tales on how easy it is to foment national identity politics. The anatomy of the extreme right’s populism that is currently sweeping Europe, contaminating and reconfiguring centrist and leftist parties’ positions on questions about immigration and diversity, by flirting with token populist statements stolen from their rival’s traditional playbooks. Right here in Quebec, this wave has arrived in manufacturing a crisis based on identity politics in the guise of secularism. And this type of fear-based politics for electoral gain is working. This cynical path Norman Nawrocki recognizes, for he is one of the signatories of the first j’accuse, Nos valeurs excluent l’exclusion devised by intellectuals soon after the Charter of Secular Values was presented this year.