I first came into contact with Theodore Harris when I was given the opportunity to moderate “Art as a Weapon: Critical Thinking and the Media,” the keynote event of Culture Shock 2011 co-organized by QPIRG McGill and the SSMU (Student Society of McGill University). Culture Shock is an annual series of events on McGill University campus focused on the stories and experiences of immigrants, refugees, communities of colour and indigenous people. This year’s keynote speakers were artists Sundus Abdul Hadi [i] and Theodore A. Harris.

I was born in the U.S. in 1966 to a biracial couple active in the civil rights movement. Our family moved from Boston to Montreal in the early 1970s; however I have always felt a strong cultural connection to Black America and some of my earliest, deepest impressions are of the 1960s in the American northeast, even though I was too young to really remember this time and place. I have found much inspiration in African American art history and especially in the Black Arts Movement (BAM) of the 1960s and ‘70s. My career has transitioned over the past 15 years or so, from social services to community work to a broader cultural work involving community art and education, situated within African diaspora histories of emancipatory education programs initiated from within the community, for the community[ii].

I immediately connected with Theodore’s art and saw it in the tradition of BAM, an impression that was reinforced as I discovered his collaborative work with renowned Black poet-playwright Amiri Baraka[iii]. Following the Culture Shock event in October, Theodore generously agreed to stay in contact with me and to discuss his work and ideas. The following conversation represents some of the issues we have been engaging with by email and telephone in the past six weeks.

Rosalind: In addition to my appreciation of your artwork Theodore, my motivation for initiating this dialogue is my research, which explores the potential social, cultural and economic benefits of inter-generational art education that is critically and culturally grounded in the lives of Black community members. My key interests right now are (a) understanding how the notion that visual ‘art isn’t for Black people’ is perpetuated both within the community and in art discourses; and (b) working with other community members to advance student-centered, critical multicultural approaches to art education that work to broaden conceptions of ‘art’ and ‘artist,’ and seek to examine and dismantle the powerful traditions of racism and ethnocentrism ingrained in the histories of Western art and art education.

Last summer I discovered a study by art education scholar William Charland in which he addressed what he described as the “Black avoidance of art as an area of study or career aspiration”[iv]. Charland examined the attitudes and behaviours toward visual art and the career identity of ‘artist’ of fifty-eight African American adolescents from four different high schools. The teenagers were asked to describe stereotypes what they believed White people attributed to Blacks, and then later in the study were asked to relate widespread stereotypes that people have of artists. Charland found, for example, a “startling overlap between informants’ understandings of society’s demeaning stereotypes of artists and African Americans” (i.e., both as poor, marginalized, moody, unable to function in ‘normal society’, etc), suggesting that “an African American adolescent who assumes the mantle of artist willingly takes on social stigma aligned with racial stereotypes as well”[v]. The teens also talked about family and community objections to an art career, something I hear often as well, suggesting that stereotype-informed beliefs about artists exist across generations.

So Theodore, given the exclusivity and elitism of formal institutions of art and what Charland describes can you talk about how you became an artist?

Theodore: First I want to thank you for moderating the keynote panel with the great artist Sundus Abdul Hadi and myself as part of the Culture Shock events at McGill University.

This is a great question and one that gets to the heart of some deep concerns for me. I was born in 1966 in Manhattan, New York City, but I grew up in Philadelphia. My mother was a single parent with a drug addiction raising my sister and me, while my father was still in New York dealing with his own addiction (which he did manage to control enough to obtain a degree in social work from NYU). I say all that to say with all of this dysfunction my parents respected the arts; my mother could draw and play the piano very well, so music was for the most part was dominant art form in our lives, not visual art. Jazz was always playing and I am very grateful for that because it has had a great influence on my life and work. You see, my mother also worked at Aqua Lounge Jazz Club on 52nd street in West Philly, where greats like Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, and Art Blakey and The Messengers played and she also hung out with them. My mom was into music in a deep way and I think music was the thing that made her the most happy.

As early as I can remember I was always drawing, whether I was in school or at home, and my mother always encouraged me to make art, but I don’t remember any one saying you should go to art school, or college period, and this is something I just started thinking about within the last few years—why wasn’t the idea ever put out there? The only person that was, somewhat, of a father figure in my life was my grandfather, who tried to discourage me from the arts. He knew nothing about the visual arts and for some reason thought art was not reliable, in other words, ‘how can you make money from it?’ At this point I was into graffiti, so one thing he did because I guess he could see I was not giving it up, he got me a job working with a sign painter and sign builder named Mr. John Wilson and I loved it. Working with Mr. Wilson was the first time I ever held a paint brush.

Art is not promoted as a career choice in inner city public schools, which is why, among other things, I left school in the 11th grade and hung out in libraries and bookstores in the art history sections trying to figure out what life and art were about. My life is all about art, it is how I see life, I guess that is because it is the only thing I have that I think I do well. And although we lived below the poverty line, I always felt like with art I was intelligent and could make some kind of future for myself if I could stick with it. And as an artist you know what I mean, you eat and sleep art.

I am sure that reading about art and artists also improved my reading skills, because you are not just reading on the surface, you have to know what those words and metaphors mean and in turn you learn about the world through art and artists and come to understand that the block you live on is not the whole world. In my opinion this is why art is not taught in public schools in the inner city, because it teaches you how to think and understand images and that is what the business class does not want you to do; become a critical thinker and an intellectual. They don’t’ want another Frederick Douglass, James Baldwin, Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez, Howardena Pindell, Betye Saar, Romare Bearden, Augusta Savage. Because these visual artists and writers force you to see your self in the world, although you may disagree with what you see in the mirror they are holding up to you, you have to deal with it.

Yes, the art world is elitist and backward in its politics, because it is mostly managed by what Hans Haacke has called “Museums, Managers of Consciousness:” the 1 % class born into money who think that art is all about aesthetic pleasure, which is why war profiters see innocent people on death row or killed in war, as collateral damage. And that drove Walter Annenberg and the blue bloods of the art world crazy: in their world art is used to disenfranchise people in the under class through promoting European art as the standard of what is human and intelligent and the rest of us as primitive and subhuman. My visual art became blatantly political after I heard and read the poetry of Sonia Sanchez; I think it was because her use of metaphors made me see what I could create with visual art, and the poetry was also a history lesson, that made me see myself in a new way. After this I went right out and read more of her poetry and the writing of other poets and got into reading the literature and literary history of Black America and this opened up a new world to me. I fell in love with literature and it inspired and added meaning to my artwork; before that I described my work as “just pretty colors,” I was painting mostly flowers, still life and art historical subject matter and was preoccupied with mostly formalist concerns.

The Charland study mirrors my experience, but some how I ignored the un-constructive things people would say to discourage my art and becoming an artist and kept going, because art was the only thing I had to hold onto and it kept me in museums, bookstores, libraries, and out of jail.

Rosalind: Can you talk some more about your early influences and mentors? Did someone or something in particular teach you that a Black man could be an artist?

Theodore: Off the top of my head, it was that the more books I was exposed to with African American artists’ work in them and the more African American artists I met; that was how I knew I could pursue art. Artists such as Charles White, Elizabeth Catlett, and always staring at those Blue Note [jazz] album covers reflected something back at me that was so powerful it even made me change the way I dressed; I started wearing suit jackets, dress shoes. This in effect causes you to walk different and you take your self more seriously, you see yourself, community and world view differently and this shapes your art. The more you know about the world the more you can teach yourself and your children to think globally. That is why I refuse to be called a minority just because most of America claims the social construct of whiteness. I am a citizen of the world and most of the world is made up of people of color, which makes them, the whites, the minority.

Rosalind: I find this so important Theodore; it really underscores the significance of ethno-cultural influences, and how, even in the absence of direct mentorship, access to cultural history and art that we can relate to our own lived experiences can make all the difference in our lives.

I can see your concern with the global picture particularly in your anti-war pieces, and in the ways they raise questions about America’s place on the world stage. Can you speak about the emotion and particularly the notion of violence for example, in the Collage and Conflict series? I’m curious about whether you would describe art as a non-violent response to violence, and how you understand the use of art as a weapon.

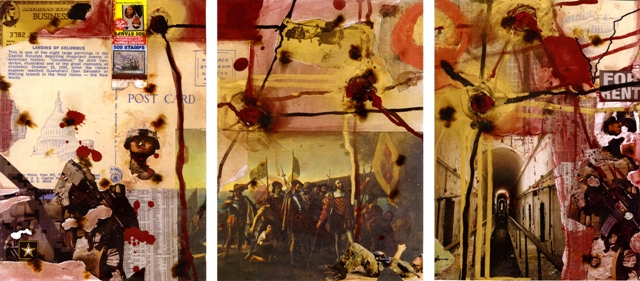

Theodore: Yes, it is a non-violent response to violence in our homes and interpersonal relationships, but most of all it is a critique of America’s domestic and foreign policy, its self destructive militarism in the name of democracy. The Collage and Conflict series began as a compositional challenge to myself because I wanted to see what would happen. Working with the three panels all at once opened me up to experimenting with the surface, and I decided to attack it—to go to war on the surface by writing curses, setting it on fire, hitting it with a hammer, ripping it apart and putting it back together—and have figures in the piece attacking each other to raise the issue of ‘friendly fire.’ Bloody flesh wounds on the panels are meant to give the viewer a visceral feeling, as if they, their flesh, are being struck by a whip or a drone missile. And the blood that is spilled is a mirror in which I see the middle passage; our flesh in knots, fire-hosed with the slobber of biting dogs and pepper spray, under the orders of Sheriff “Bull” Connor, whose mouth is a little white tank moving backwards, camouflaged with Kara Walkers’ silhouettes.

I see art as an offensive and defensive weapon to defend your self and community, as it was in the great work Emory Douglas made for the Black Panthers’ news paper—I would say Emory is a Charles White turned up a few notches. Because of the influence of documentary film on my work, I would say the Collage and Conflict series are cinematic confrontational collages; cinematic because I see the juxtaposing and layering of images as creating a sense of movement as captured in film stills, and confrontational because of the weight of issues the work is dealing with. My work is about looking beneath the “Surface Politics” of aesthetics and formalism, to visualize a Black Aesthetic that is about “life over death” like Addison Gayle said.

Rosalind: I find collage to be somewhat of a ‘violent’ method in and of itself, in terms of the cutting, severing, disassociating and dislocating it involves. I notice that you refer to it as ‘surgery’ and I find your work is similar to Wangechi Mutu’s, who has also described her collages as ‘delicate surgeries.’ Both of you also use wounds in your work in similar ways. You describe war as a ‘map of wounds’ and have said that in your work the wounds might be from shrapnel, gunfire, friendly fire… I also think of those wounds in your and Mutu’s work as wounds of colonialism, imperialism, capitalism. And the violence in yours and perversion in Mutu’s work, for me, have so much to do with the violent distortions and perversion of these systems, the ways they act on human bodies—flesh and blood—and on human-ness overall. I’m also very intrigued by your identification of the Challenger explosion as a starting point.

Theodore: As an artist the goal of my work is to get the ideas in your head, so I would say Wangechi Mutu, John Heartfield, Romare Bearden, and I are attempting a kind brain surgery on the mind of the viewer, to do what Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o termed “de-colonizing the mind.” And yes those wounds are the result of damage done to our minds and bodies under capitalism, colonialism, Jim Crow, and the prison industrial complex—a plantation with stock options in sizzling electric chairs…I wonder if an innocent prisoner on his way to the electric chair, who has exhausted all his appeals to a crooked court, I wonder if he feels ‘Post-Black?’

In the two person exhibition “War is a Map of Wounds,” Howardena Pindell and I had at New Jersey City University, I had this quote by Amiri Baraka on the wall of the gallery above my work, for the most part to be directed at the art students: “It is a new world we want not an endowed chair in the concentration camp…art must be our magic weapon to create and re-create the world and our selves as part of it…This is my motto and the standard on which I make my work as magic weapons, created in the ‘Black Labs of the Heart.”

But another way to view that blood is to see it as the artist sacrifice in sweat and tears, Augusta Savages’ tears when she could not get back her sculpture “The Harp” she was commissioned to make for the 1939 New York Worlds’ Fair, that had been inspired by the song “Lift Every Voice and Sing” and was destroyed after the Fair.

I was frozen when I witnessed the Challenger explosion, the images were so powerful that I started to collage them with images of crying babies, this is how I got into collage. Then I went on from there to collaging the U.$. Capitol building by turning it upside down, first done in my collage Vetoed Dreams of 1995. Some people have asked me will I turn it right side up because President Obama is in office. Why, because he is African American?[vi] I say no way; its too early for that, like I said before the scales of justice are not blind and even, and that is why now a world wide struggle is exploding.

Rosalind: I think that may be a critical note that we might end on for now: that while our conversation for this paper has been largely driven by our common concerns and interests in relation to Black learners and communities, and Black artists and their art work, we both understand that the issues are not just “Black and White”—critical thinking, like your collages, is always more nuanced, layered and complex than that.

Theodore: From the outset it has been so great talking with you and we need you in the university and community to debunk how we see and what we think about ourselves in relation to the arts.

Rosalind: Thank you and likewise—we need you Theodore, for the exact same reasons.[vii]

[i] See Sundus’ work at: http://mesopotamiancontemplation.blogspot.com/; and

[ii] For examples see Austin, D. (2009). Education and liberation. McGill Journal of Education 44(1), 107-118; hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York & London: Routledge; Institute of the Black World (1974). Education and Black struggle: Notes from the colonized world. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Educational Review; Murrell, P.C. (1997). Digging again the family wells: A Freirian literacy framework as emancipatory pedagogy for African American children. In P. Freire (Ed.) Mentoring the mentor: A critical dialogue with Paulo Freire (pp. 19-58). New York: Peter Lang.; and Payne, C.M. & Strickland, C.S. (Eds.) (2008). Teach freedom: Education for liberation in the African-American tradition. New York: Teachers College Press.

[iii] Harris, T. and Baraka, A. (2008). Our flesh of flames. Philadelphia: Anvil Arts Press.

[iv] Charland, W. (2010). African American youth and the artist’s identity: Cultural models and aspirational foreclosure. Studies in Art Education 51(2), 105-133.

[v] Charland, p. 124.

[vi] See also David Craven’s discussion of Theodore’s work in Craven, D. (2009). Present indicative politics and future perfect positions: Barack Obama and Third Text. Third Text 23(5), 643-648.

[vii] Selected additional sources on Theodore Harris’ art:

ACRID DIALECTIC: The Visual Language of LeRoy Johnson and Theodore A. Harris. HUB Gallery Pennsylvania State University (video, 10mins, 29secs., posted online by BethanyVan, 19 February 2008). Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bwcR-HDEvRY

Brossy, J. (Producer) (2011) Collage & Conflict: Artwork by Theodore Harris at PhillyCAM http://vimeo.com/19613879

Baraka, A. (2008). The Collage Art of Theodore A. Harris. Left Curve (24), Retrieved from http://www.leftcurve.org/lc24webpages/TedAHarris.html

The Truthoscopic Collage Art of Theodore A. Harris. John B. Hurford ’60 Humanities Center Haverford College. Retrieved from www.haverford.edu/HHC/gallery.php?id=1271&p=4

Villaflor, R. and Ray, M. (2009, 26 March). War is a map of wounds: The art of Howardena Pindell and Theodore A. Harris. The Gothic Times (New Jersey City University). Retrieved from http://www.gothictimesnetwork.com/2.9689/war-is-a-map-of-wounds-1.1416054#.TtKSfFaLPEU

Theodore’s work will be featured in an upcoming group exhibition titled WITNESS: Artists reflect on 30 years of the AIDS pandemic, curated by David Acosta and presented by the Asian Arts Initiative in collaboration with Casa de Duende (2 December 2011-27 January 2012) . See http://visualaids.blogspot.com/2011/11/witness-artists-reflect-on-30-years-of.html