A Review of Louise Carson’s Dog Poems and Carolyn Marie Souaid’s The Eleventh Hour

Louise Carson and Carolyn Marie Souaid are two Montréal-area poets who as far as I know have never met. Both are women who have seen a fair share of life and written multiple books of poetry and prose. Both have published collections of poems in the last year that treat themes of nature, mortality and reckoning as their final season approaches. So why not have them meet on this web page?

Louise Carson’s Dog Poems concern the poet’s largely solitary life with her dog and cats in the countryside near St-Lazare, Québec. One feels the weight of prolonged solitude in the often-slender lines and spare imagery of these poems; however, the poems are also leavened by a bemused, often deadpan humour. Quite a few of the poems are inspired by the rhythm of her dog walking, trotting, loping along, and its sniffing, pawing, snuffling manner of exploration. Some are deliberately shaped to evoke that simple, instinctual life and the way the constant companionship of that dog shapes her.

She does-

n’t walk

she al-

most al-

ways trots.

She looks

for food

and whines

when I

refuse

to let

her cross

the road

for Mc-

Donald’s

or Tim’s

sacks, cups.

She pulls

against

the leash

unless

I cop-

y her

and trot.

(“The dog walks”)

Carson’s poems about her dog are almost all brief, and myopic in scope to suggest the dog’s elemental nature, with titles like “Each day I brush the dog,” “Alone with the dog,” “Dog … and cat poem,” “No bad dogs,” “The dog’s name is Mata,” “Barrel, stock, muzzle.” Interspersed with these are honest, direct poems about aging, difficulties of writing, the death of the author’s mother, reconciling oneself with past abusive relationships, living on limited means, and the challenges of living alone:

Living alone is bad for your health.

Fuckbuddy wants me.

Women are more likely to be assaulted by someone

they’re living with.

My ex assaulted me at the beginning

and end of our relationship. Neatly bracketed.

Sitting for more than four hours is bad for your health.

Sitting writing for the last twelve years, I gained

weight but was able to survive the last twelve years.

(“Proposition/Observation”)

Amid these short poems is the powerful and courageous “Cancer Suite,” which concerns Carson’s harrowing experience surviving lymphoma. But also to be found are poems celebrating the joys of writing, Carson’s loving relationship with her daughter, and the simple pleasures of a good day.

Are these poems great? There is awesome reckoning in “Cancer Suite.” And the rest of the poems – all, as I said, short, or pretty short – do what they want to do, are written with knife-like concision, and have cumulative effect. Carson’s ironic awareness of her own limitations disarms with bittersweet charm. As the introductory poem, “One dog more,” puts it,

(These poems are humble, like a dog,

and, like a dog, are also thieves,

and bad actors.)

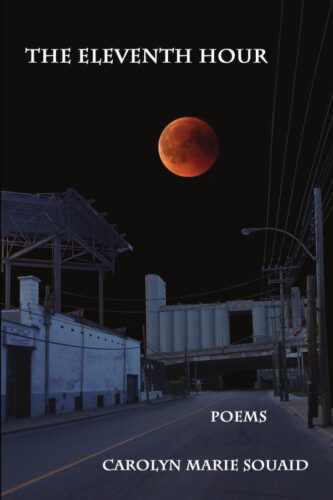

In The Eleventh Hour Carolyn Marie Souaid, like Louise Carson, concerns herself with aging, dying, and other limiting realities. But Souaid gives greater focus, as her title suggests, on the urgency of little time left; indeed, her keen sense of mortality heightens an anxiety-edged but ecstatic awareness that this is it. Light is a common image and metaphor, in all its mystical, ethereal implications.

I awoke to handfuls of light,

the cool wind pressing through a window.

Undulating curtains.

My blood sugar spiked, energy pumped

through my body’s meridians.

I was as open

as new life blinking into the sun

for the first time,

a blank slate, ignorant

of our long, dark, collective history:

sooty traces of the Industrial Revolution

coating our lungs.

(“And So, the Wind”)

Strolling by the river in a halo of light

I notice a dozen flies swarming

around death.

I am contemplating vantage points.

The bird’s head is crushed velvet,

blue and iridescent.

(“Amplitude”)

Countering this vision are frankly observed, constraining realities, in all their banal concreteness. Souaid’s dying father is the subject of several poems, poignant, elegiac and at turns humorous, such as this straight-forward but nevertheless complex portrait entitled “Pre-Op Checklist”:

Wheeled to the elevators

he is asked for the last time

before surgery what he has to declare

besides a watch and underwear.

Pills, nope.

Dentures, nope.

Cane, pace-maker.

Nope, nope.

Heart attack?

At his age, they expect decline.

A startled mouse not a full-scale carnivore.

This description would suggest he’s still a fierce customer, and undoubtedly he is; yet at the end of the poem, gentler qualities emerge, again bathed in light:

He is less engrossed in things than he was,

say, yesterday or the day before,

or a lifetime ago

on the Isle of Capri with his youthful bride.

The world that makes him happiest now

is a square of sunlight,

where Mother prepares his ham sandwich

the way he likes it, on a sesame bun

with mustard and lettuce.

Similar poems – similar in how affirmations are salvaged out of the foibles and obstructions the everyday throws up against desire – are “Exercise in Stillness,” “Their Death Projects,” “This Finite Moment,” “Still Life With Slippers,” “This Ordinary Life,” “Northern lights, Kangiqsujuaq” and “Timeline.” Notable also are a couple of poems concerning the Ethiopian Airlines Boeing Max 8 flight, downed in 2019. Souaid’s cousin’s 24-year-old daughter was killed on that flight. Unforgettable is the irony of the Exit sign on the crashed plane.

A favourite poem is the final one, “Arthur,” which in its graceful way is emblematic of the charms and preoccupations of this collection. An old sparrow lands on the ledge by the window beyond the writer’s desk. It’s a repeated occurrence, and she affectionately comes to call him Arthur.

He’s like a nervous man in a tweed coat,

scurrying across the street

with a newspaper under his arm

but in all his ordinariness, arriving “gently on the wing of dawn,” he becomes a symbol for a mysterious transcendence beyond death:

… I believe

that long after my ashes have cooled,

that dear bird will find me again

wherever I am, in the web of silence,

the way he finds me now,

with my sleeves rolled up

and some tea in a pot, steeping.

The Eleventh Hour is a favourite collection of those by Carolyn Souaid I own and have read. They show a seasoned poet at the height of her powers.