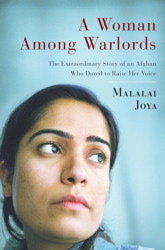

Reading A Woman Among Warlords you may find yourself forgetting on occasion that this is, in fact, a work of non-fiction, so extreme are the terms of its author’s life and homeland. The youngest MP ever to be elected to Afghanistan’s parliament, Malalai Joya was kicked out in 2007 amid cries of, “Take this prostitute out of here!” Her crime had been to challenge the legitimacy of a parliament and judiciary, largely composed of warlords, drug barons, fundamentalists, qualified by the participation of intellectuals and justified by the protection of NATO countries such as the US and Canada. Here is the one of the women NATO governments claimed they were going to war to help. There is a certain shock value in the details of just how far from such a mission our governments have strayed, how far from grace they have fallen.

Reading A Woman Among Warlords you may find yourself forgetting on occasion that this is, in fact, a work of non-fiction, so extreme are the terms of its author’s life and homeland. The youngest MP ever to be elected to Afghanistan’s parliament, Malalai Joya was kicked out in 2007 amid cries of, “Take this prostitute out of here!” Her crime had been to challenge the legitimacy of a parliament and judiciary, largely composed of warlords, drug barons, fundamentalists, qualified by the participation of intellectuals and justified by the protection of NATO countries such as the US and Canada. Here is the one of the women NATO governments claimed they were going to war to help. There is a certain shock value in the details of just how far from such a mission our governments have strayed, how far from grace they have fallen.

The beauty of the book Malalai Joya has co-authored with Derrick Okeefe is that it rings with reality, as lived and understood by an Afghan woman, wise with words by dint of an education and politicization. The truth of that reality here brims with good people, bad people, and fearful people, crimes of the most egregious nature are detailed and their perpetrators named.

Sure to be one of a kind as it mixes diverse genres: personal anecdote, history, socio-political analysis and political manifesto. It is also a personal appeal to the reader, to understand both the historic and present roles played out by foreign governments, occupation forces and corporations in both funding and implementing the tormenting and terrorizing of ordinary Afghan people and the destabilizing of their country.

To this end, tragedies are spelled out: wedding parties are bombed and civilians killed in the thousands, the infrastructure wasted, food crops turned to heroin crops, children forced into labor, women forced into abusive marriages, women who self-immolate in sheer despair. This is the country with the lowest longevity where most people still do not live beyond the age of 43, thanks to a grueling poverty, that in itself testifies to the contradiction and futility of aid carrying a gun.

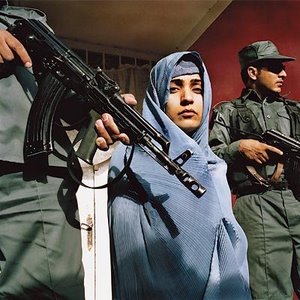

There are victories too, so few and so hard won that they are indeed precious and moving. Malalai’s election and this book must surely count as two of these. The subject of hate campaigns, attacks and death threats, Malalai is kept constantly on the move and her precise whereabouts a secret. The blue burqa she must wear becomes a life saver, as it blends her into a sea of other burqas. This paradox also provides a useful metaphor, for though on the one hand she cuts a heroic figure, on the other, as Malalai readily maintains, she is just one among an ever growing number of Afghan women and men, fighting for women’s rights and a democratic Afghanistan. This is a movement largely growing underground, demonstrating great courage and community in the face of mortal threats by warlord militias, and fundamentalist policing that preaches a woman should be “in her house or in the grave”.

There are victories too, so few and so hard won that they are indeed precious and moving. Malalai’s election and this book must surely count as two of these. The subject of hate campaigns, attacks and death threats, Malalai is kept constantly on the move and her precise whereabouts a secret. The blue burqa she must wear becomes a life saver, as it blends her into a sea of other burqas. This paradox also provides a useful metaphor, for though on the one hand she cuts a heroic figure, on the other, as Malalai readily maintains, she is just one among an ever growing number of Afghan women and men, fighting for women’s rights and a democratic Afghanistan. This is a movement largely growing underground, demonstrating great courage and community in the face of mortal threats by warlord militias, and fundamentalist policing that preaches a woman should be “in her house or in the grave”.

Not surprisingly, Malalai speaks and writes with the urgency of a woman who counts every day of life as a day won and not to be wasted. She writes with great pride and affection of an Afghanistan that’s rarely ever been mentioned in the western corporate media that prefers to cast this land in the light of a primitive country full of backward people with neither the inclination nor the culture to manage themselves in a civil fashion; a people who must, therefore, be bombed into the sort of democracy that only criminals are fit to defend.

Malalai’s book serves as a counterweight to such constructed news and views, citing history and culture of the struggle for Afghan democracy, with the likes of Amanullah Khan and Queen Soraya, the parties and organizations in the Afghanistan of the first half of the 20th century. All of which sowed the seeds of a constitutional monarchy and a more egalitarian society, that saw women enter parliament and many areas of the labor force. Such homegrown evolution suffered serious setbacks however under direct Soviet influence in the 70’s that culminated with Soviet occupation in ’79, all amid the cold war machinations of the US and the latter’s funding and arming of extremists that would, in turn, fuel the bloody civil war of ‘92-’96 and ongoing instability.

The democratic urge has surely taken a severe beating and yet Malalai finds reason to be hopeful. She writes, “The support I received in the election campaign proved that the inequality between men and women was not some kind of permanent part of Afghan culture – things could be changed for the better.” Most of the religious leaders in her province of Farah supported her too. And she recounts many expressions of Afghans passionate longing for an end to corruption and violence and the beginning of a better world for their children. One man tells her, quite simply, “I want to put my hat on your head and your scarf on mine.”

The poignancy of this voice stands in stark contrast to the cynicism she encounters elsewhere. In the interests of realpolitik, Malalai has frequently been asked to forgive and forget the “mistakes” of the past, the contradictions of the present, and to compromise a little. To the Italian journalist who asks her why she doesn’t try a more diplomatic approach, she replies with the question, “Would you have compromised with fascists like Mussolini in your country?”

Malalai maintains that guns are clearlynot the best way to win a democracy. She argues as an educator who understands democracy as a matter of process, discussion, education. Nevertheless, she does distinguish democracy from freedom. Where Afghan freedom is concerned, she is prepared to do what Afghans have done before, as they did with the British and the Soviets, and that is to defend it to the hilt.

Presently, Afghans remain “trapped between two enemies”, NATO forces and the Taliban. Malalai reasons that leaving Afghans with the one enemy invader to conquer would give them a fighting chance for a free Afghanistan and the eventual possibility of diplomatic resolution of her country’s regional differences, in an Afghan way, at an Afghan pace. With this in mind, she urges “democracy loving people”, Canadians among them too of course, to do whatever we can to get NATO forces out of Afghanistan. Evidently, large anti-war demonstrations and opinion polls here in the West do not go unnoticed among the “democracy loving people of Afghanistan”.

The thing about Malalai Joya is that she really believes that when enough people become aware, “they will rise like a storm that brings the truth.” Her book ends with an Afghan proverb, “Our enemies can cut down the flower, but nothing can stop the coming of spring.”