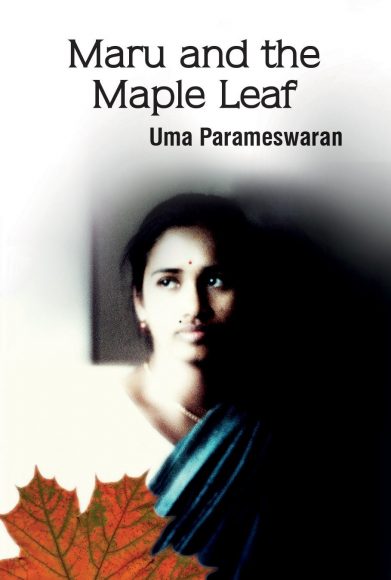

Maru and the Maple Leaf by Uma Parameswaran, Larkuma Publishing, 2016 (367 pages)

Uma Parameswaran, a retired professor of English (University of Winnipeg) and well known author with a special interest in women’s literature and South Asian culture, has cleverly crafted her recent novel around the writings and experiences of Maru, an Indo-Canadian woman from Winnipeg. A work of fiction, the book includes many of the author’s earlier excerpts from essays and stories. The name “Maru” can be seen as a short form for “Uma Parameswaran,” the nom de plume that Maru uses in her writings (sometimes spelled as “Uta” Parameswaran). Fact and fiction are thus entwined with motifs of familiar and unfamiliar names woven around the incidents and characters that shape this book.

The narrator, Priti Moghe, is a resident physician in obstetrics. She is very busy with her hospital shifts and with her boyfriend, Stephen Woodhouse, a fellow resident in general surgery. Priti’s lifestyle is suddenly interrupted by the death of her dear Aunty Maru who has left her a legacy of cardboard boxes filled with journals, letters, essays and stories. Priti is baffled by all these typed or handwritten foolscap sheets. Some have dates, others don’t. Some are fragments or incomplete anecdotes. The stories capture the mind of the reader, but the journey that Priti takes us through is confusing. Do these sketches reflect Maru’s life? Are they instead about the women she met? Some of them seem to have been based on women that Priti had come to know through Maru. Have these stories been embellished? Are they fact or fiction? The questions are there as teasers as both Priti and the reader begin to realize that the spirit behind Maru’s writings lies elsewhere.

The novel takes us into different time zones: the present with Priti, Stephen and Uncle Siv (Maru’s husband), and the disparate and confusing time zones in Maru’s own past. Characters and incidents from India combine with speeches delivered at writers’ organizations and minority women’s groups in Canada. The maple leaf and the Assiniboine and Red rivers thus become as powerful as the Kaveri, the Godavari, the Krishna and the Ganga,[1] and somehow, sifting through all this vast range of rich imagery, Maru seems to draw strength from experiences, real or imagined. On the other hand, she does not fail to observe how there is no escape from class-consciousness:

“When one leaves a class-conscious homeland, one usually assumes it is behind for good. But oh no, it is alive and well in Canada, and let no one say otherwise; and when anyone talks about class and gender oppression in other countries, I hope you’ll have the courage to show them around our own city.”

We meet the mysterious Chikkamma, “born about the turn” of the “last century.” She earns a graduate degree to become a school principal. At the age of 28, she falls in love with a married man, marries him, and has a son. Bigamy in those days was not a crime, nor was it common for women to graduate from universities and hold jobs. Chikkamma remains a significant figure in the book. She appears as a strong woman, ready to take on the world and ready to offer her advice or support even if it is for unclogging a toilet bowl blocked with bread-bagging plastic. “Women of Maitreyi Nivas never walk out on a job,” she says.

There is also another motif from India’s ancient past, built around complex traditions and incidents from the great epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Maru narrates the story of Panchali’s swayamvara, where Panchali chooses Arjuna for a husband instead of the glorious Karna, the charioteer’s son, whom she seemed to love more.[2] Panchali’s story, like many others in the book, reflects our choices in life, the consequences that follow, the connections, and the learning that takes place from the experience.

Parameswaran is very skilled in exploring centuries of relationships and bringing them together to a place in time that transcends a linear, chronological sequence of events. What happens or will happen depends upon who we are and what has shaped us: our history, ancestors, language, culture, the people we meet and even those we do not meet. Our stories speak to us and to those who come after us, very much like Maru’s poem “Apsara Love,”[3] where she longs to go “Far from here where all ever is.”

Maru and the Maple Leaf explores a vast canvas covering the span of many lifetimes. Maru’s struggle in Canada in the 1960s is not unlike Chikkamma’s struggles in the early 19th century, or Priti’s struggles with premature babies in maternity wards. If we could, like Maru, write about our lives and leave behind words and experiences to be picked up by others, we could continue to travel forever on unbeaten paths. I will conclude with Maru’s words of wisdom:

“Mortals are supposed to honour their forebears – that is what life is all about, that is what civilization is all about, to give continuum to all that is worth preserving. And the spirits have to depend on us humans. And I have failed Chikkamma.

Find out the details, dig around, that is what biographers are supposed to do, she said. But I am not a biographer, just one who wants to tell stories, women’s stories, so we can know ourselves through others.”

Parameswaran has written a well-crafted, intriguing novel about re-discovering one’s roots, connecting with the past, and shaping the present through a wealth of new experiences.

[1] Kaveri, Godavari and Krishna are names of rivers in Southern India.

[2] The story of Panchali, also known as Draupadi, is from the Mahabharata. Swayamvara is an ancient practice where a young woman of marriageable age chooses a husband from among many suitors. Karna and Arjuna were two suitors at Panchali’s swayamvara.

[3] Apsara is a female spirit or heavenly woman.

** Please note that this book is currently out of stock with the publisher, but is available with the author at: uparameswaran@gmail.com