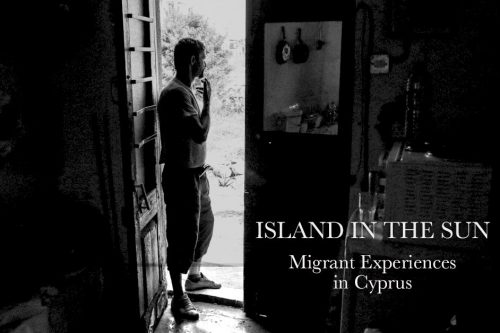

The desires for freedom, safety and self-determination move people across the globe, away from familiar landscapes and across geographic borders. Lack of these basic necessities has led many to Cyprus.

The second largest island in the eastern Mediterranean, Cyprus is surrounded by Turkey to the north, Syria to the East, and Egypt to the south. With over 2 million visitors a year, it is a popular tourist destination for EU, Russian, and Turkish citizens.

Passengers arrive at Ercan Airport in the Turkish-Cypriot Administered Area (a self-declared state that comprises the northeastern portion of the island of Cyprus recognised only by Turkey)

Growing up in Turkey, my husband visited Cyprus frequently in his childhood. Short-term vacation trips with his parents and brothers are special memories for him. In 2012, my in-laws moved to the island’s Turkish-occupied north, just 70 miles south of Turkey’s shore and 75 miles west of Syria.

We started visiting them in Cyprus, and with each visit we got to know the island better. Little did I know that I would discover a not-so-well-kept secret. Amidst the hustle and bustle of Cyprus, a major landing point for migrant workers from Southeast Asia, North Africa and Eastern Europe, the sex-trafficking and forced-labour industry is quietly thriving.

Looking at the US Tip report for the past years, there was clear evidence that the island was struggling to comply with the Trafficking Protection Act.

Despite the devastation that followed the Turkish occupation of Northern Cyprus in 1974, the so-called “economic miracle” of the late 1970s and 1980s brought growth to the Republic of Cyprus. A lack of low-skilled labourers prompted Cyprus to open its doors to foreign workers in 1990. Its decisions to abandon its restrictive immigration policies and join the EU in 2004 have lead to a steadily increasing immigration rate on the island over the past two decades.

As growing numbers of people displaced by nearby conflict zones try to reach Europe, the island’s vulnerable populations have also increased and have proven to be an easy target for exploitation. In hopes of escaping the cycle of poverty and hardship, families and young adults in developing countries sign away their homes or take out high-risk loans, all to pay thousands of dollars to so-called employment agencies to obtain work visas overseas and thereby enter Cyprus. For many people the future looks quite somber, and without much to lose, people take a chance when offered a lucrative job, hoping to reach something better on the other side.

After the oil drilling company in his home region of Gorj, Romania, laid off its workers, Ilie was left without income in one of the poorest countries in Europe. Following job leads from his former co-workers back home, Ilie saved up for a flight to Cyprus, where he was hoping to find better living conditions and financial stability for his wife, son and blind mother, whom he had left behind.

Working with heavy machinery for a construction company, Ilie had a tragic work accident while handling a gas barrel that exploded right in front of him. When he was rushed to the hospital with severe burns, he found out that his employer had stopped paying for his insurance after only a couple of weeks. Despite taking antibiotics and other medicine that was affordable, the health care Ilie received was insufficient. After a year and a half, his leg is still infected and his daily life is seriously affected by the injury. Currently he has no income and lives in a barrack without electricity or water. Until his healing is complete, he won’t be able to take another job offer. He longs to go home and be with his family.

Many of the foreign workers expect to arrive in mainland Europe with fairly good integration policies and welcoming communities, but instead end up in contested areas where the media and public debate focus on allegations that migrants and asylum seekers receive too many benefits and are responsible for the rise in crime, road accidents and diseases.

Although the land is divided, victims of trafficking that are being held by corrupt businesses are regularly trafficked across the partition between the Turkish-Cypriot Administered Area in the North and and the Republic of Cyprus in the south. Ironically, police and government officials on either end of the conflict struggle to co-operate, while the mafia on both sides collaborates well.

Limassol, Cyprus. 2015. The buzzing nightclub scene, bars and cabarets attract huge crowds of foreign tourists who fly in from Europe, Russia, Turkey and the Middle East.

Following the abolition of the casino and cabaret industry in Turkey in 1998, a multitude of bars, cabarets and newly-built resorts moved to the nearby island, marking the shoreline with their neon flashing signs. Cyprus is rapidly transforming from a traditional tourist destination into a “New Las Vegas” of the Mediterranean.

Recruited by corrupt employment agencies abroad, many migrants are being coerced into low-income jobs in the tourism and nightclub industry, domestic work and the agriculture sector. A number of them end up in situations of forced labour, prostitution and inhumane treatment by their employers, with little to no time off. Domestic workers, with slave-like working conditions and an average net salary of 309 Euro a month, become trapped in employers’ houses and are totally dependent on them for their well-being.

Without knowledge of the local language and labour protection rights, many of the migrants find themselves stranded or homeless with expired work permits, while their families at home continue to have high expectations for them to succeed and one day return home.

Despite her college education, a young girl from South East Asia couldn’t find a well-paying job after months of job-searching. Her aunt urged her to go overseas to find higher-paying work and better opportunities. Through an employment agency, she was promised a job as a waitress. When she arrived, the young woman ended up in a cabaret as a sex worker and was locked in at her madam’s home. She took a knife into her room and was considering suicide, but decided to fight her way through it. She was eventually able to escape and reunite with her mother who was grappling with cancer.

A young woman from South East Asia was granted a residence permit after being rescued by the trafficking division of the police in Cyprus. After co-operating with the police, she now is living in an apartment of her own. With help from local NGOs, she found a job in a local restaurant, which enables her to slowly pay off the loan that her parents initially took to finance her trip to Cyprus and ultimately return home.

A young migrant worker from India was found dead after apparently falling from the 5th floor of the apartment building where she was employed as a domestic worker. The migrant community, together with the non-profit KISA, requested an independent inquiry.

Her death, KISA asserted, was either the result of a criminal act or most probably “an accident in an effort to escape from the flat she was kept in against her will.” Several domestic workers had left the employer before her, due to the rough and humiliating treatment, KISA said.

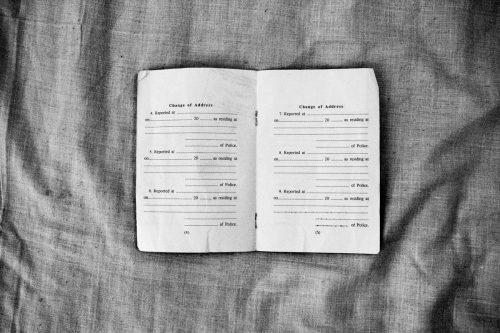

With no right to civic participation or labour protection, the fear of repatriation is a constant threat. Debt bondage, threats and withholding of wages paralyze the migrants from seeking help from the local police or immigration lawyers. The restriction of movement through confiscation of passports and personal documents by the agents and employers makes it difficult for the migrants to establish their legal identity and seek help or receive government services and relief. In some cases, suicide offers the only way out of the dilemma.

Non-profits on the island are endlessly on the move trying to prevent and intercept trafficking. Safe houses and transitional apartments are available, though access is limited. Outreach programs are providing job training and mental health support. Finding a source of regular income is crucial in helping survivors recover and get back on their own feet.

Survivors sometimes have to wait up to 6 months to start receiving benefits after they are recognized as victims of trafficking. Until this happens, the government offers no financial support. If they don’t find a job in the meantime, they are at the mercy of charitable acts and support from local non-profits.

Although migrant workers contribute significantly to the Cyprian economy and everyday life, they are completely overlooked in policies and legislation on issues of integration, violence against women, exploitation and trafficking of human beings. Over the past number of years, only a few cases have been brought to light, revealing the vulnerable conditions of these workers and the context in which trafficking and forced labour develop. The issue remains invisible.

North Cyprus shoreline

Back in 2012, the Republic of Cyprus was ranked Tier 2 on the Watchlist, which means that while the minimum standards of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act were not being met, the country was making an effort to combat trafficking. The Turkish-Cypriot Administered Area in the north (which is not recognized as a country by the international community) was ranked even lower – Tier 3 – which means it was considered a zone of impunity for trafficking and forced labour.

Today, only the Republic of Cyprus has made improvements over the last couple of years.. The police’s sex trafficking division has increased its raids on bars and nightclubs, but only a handful of convictions have been obtained in the last year.

There is still much progress to be made.

Maren Wickwire, originally from Germany, is the founder of Manifest Media, where she produces documentary films, web-based educational narratives and multimedia installations, raising awareness for human rights issues. As a director, editor and cinematographer, she has been collaborating with internationally recognized organizations including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, the US Institute of Peace, Art Works Projects, the National Public Housing Museum and Eastern Congo Initiative, to name a few.

Maren’s award-winning multimedia works have been screened globally. She uses film as a tool to raise awareness and give a voice and face to the untold stories of injustice. This photo essay is an adaptation of what appears on her website at: http://www.marenwickwire.com/cyprus.

Whoever wrote the caption for the first picture needs to do better. The long caption refers to “the Turkish Republic of Cyprus”, which is both inaccurate (the correct term is “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus”) and contentious. The author herself does not use this term (correctly pointing out that “The Turkish North (…) is not recognized as a country by the international community”.

Thank you Maren Wickwire for your work.