The same technologies used to obliterate are also used to narrate. Maps and images are not neutral. I often think about what is lost in the shutter’s operation. The precision it promises comes at the cost of everything that cannot be measured. The journey, too, is not linear—it spirals inward, asking: How do we carry within us a world that is always under threat of erasure?

I’ve learned to trace the curve of my childhood street, now rendered in pixels, flattened into a grayscale geometry of targeted zones…

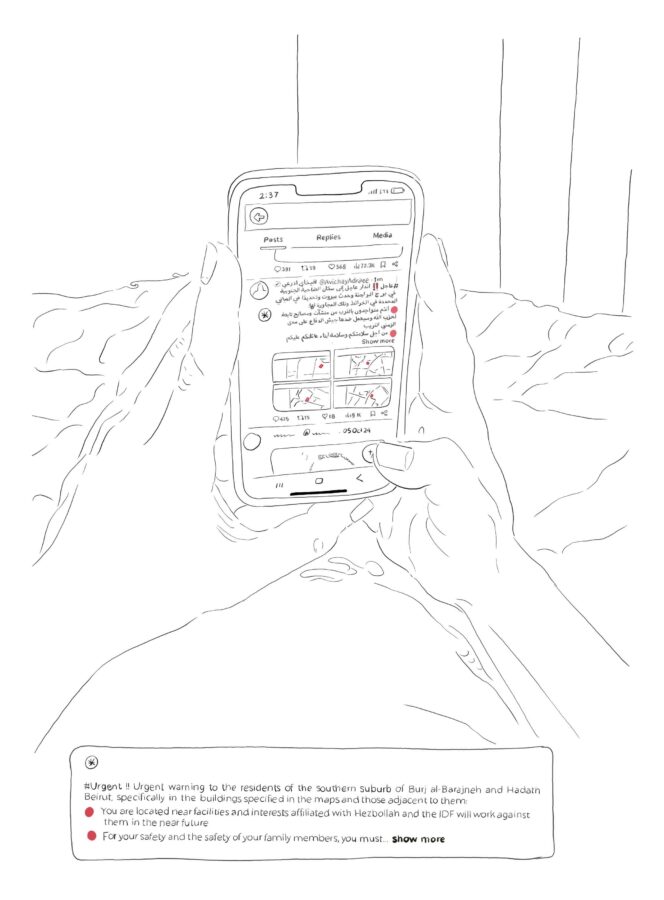

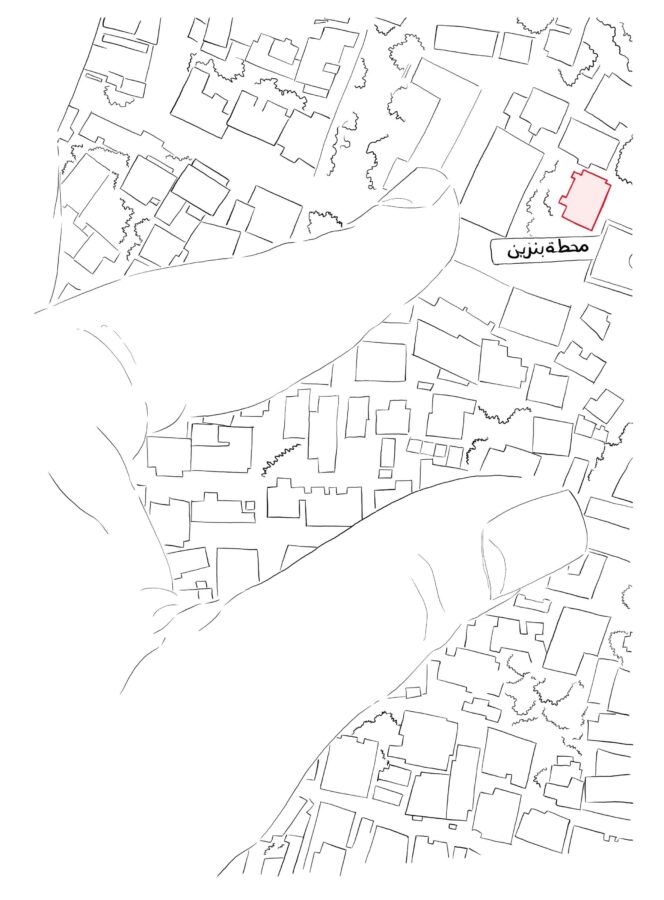

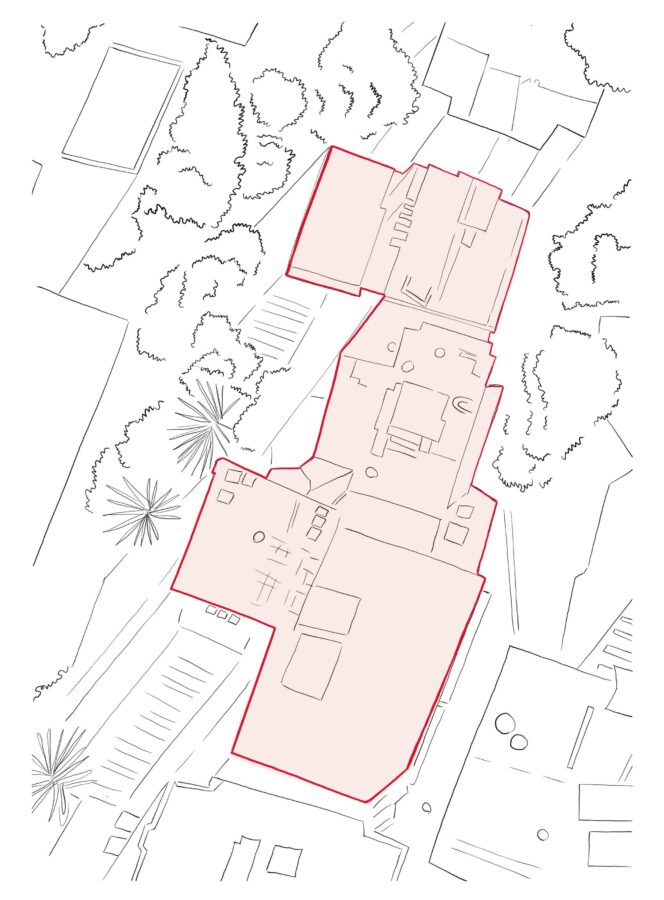

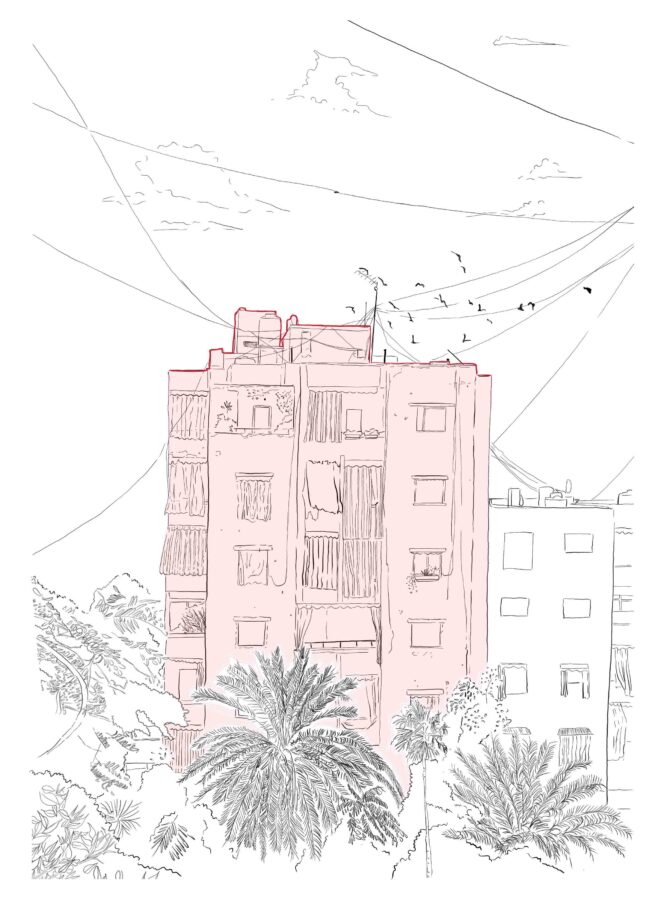

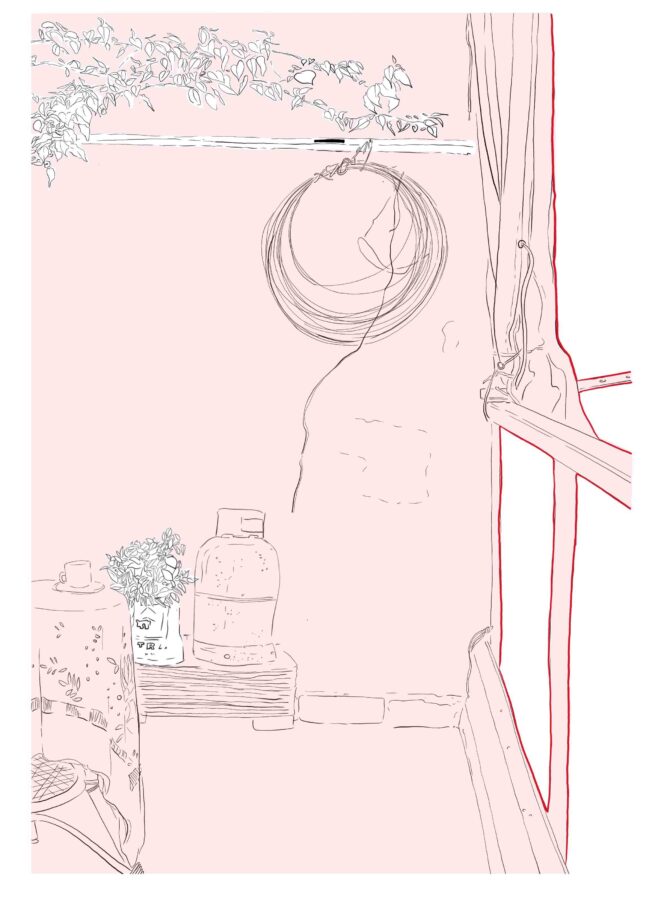

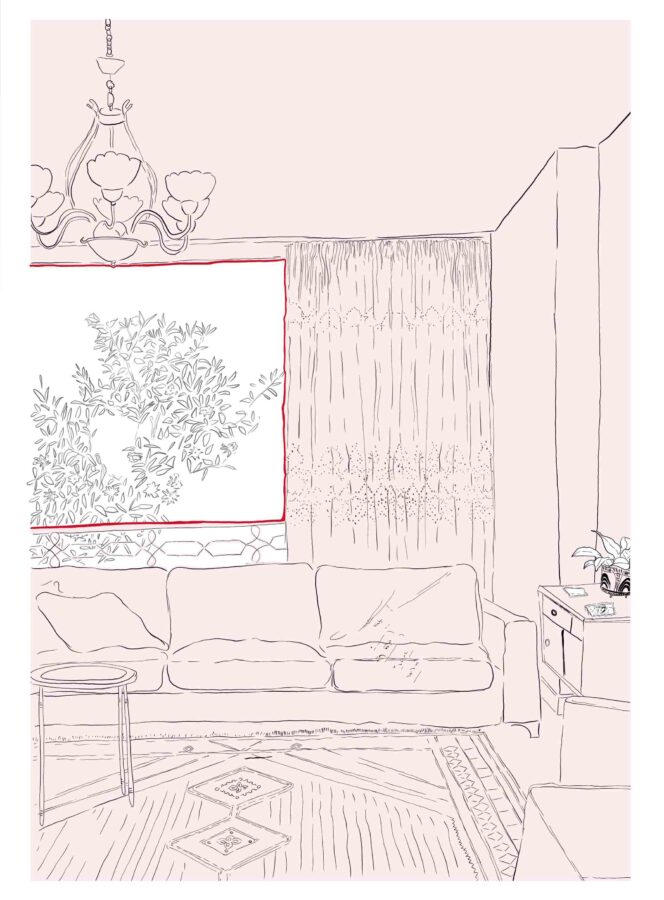

Over the past year, I’ve learned to read satellite-image maps.* I’ve learned to trace the curve of my childhood street, now rendered in pixels, flattened into a grayscale geometry of targeted zones: The gas station at one end, a Palestinian refugee camp at the other. There’s the building where I grew up, beside Moussa’s coffee-roasting shop and Sameer’s pharmacy. I slide my finger across the screen, estimating the location of Haseeb’s butcher shop, where we bought meat for kibbeh nayyeh on Sundays. The Menshiyyeh bakery, where I made my first manouche—too heavy on the za’atar. The garden where we gathered grass for the rabbit we raised on the balcony. And the cemetery where my father is buried—his grave, half in shadow, half in light.

And just above the map, a tweet. A clinical, urgent notification of displacement delivered with the cold precision of code. I stare at the screen. My mind lingers on the faces of neighbours and strangers who still live there, on the unbearable clarity of a machine that knows exactly where and when to strike. In these moments, I feel my breath tightening, not from anger alone but from the disjuncture in time, the dread of impending disaster.

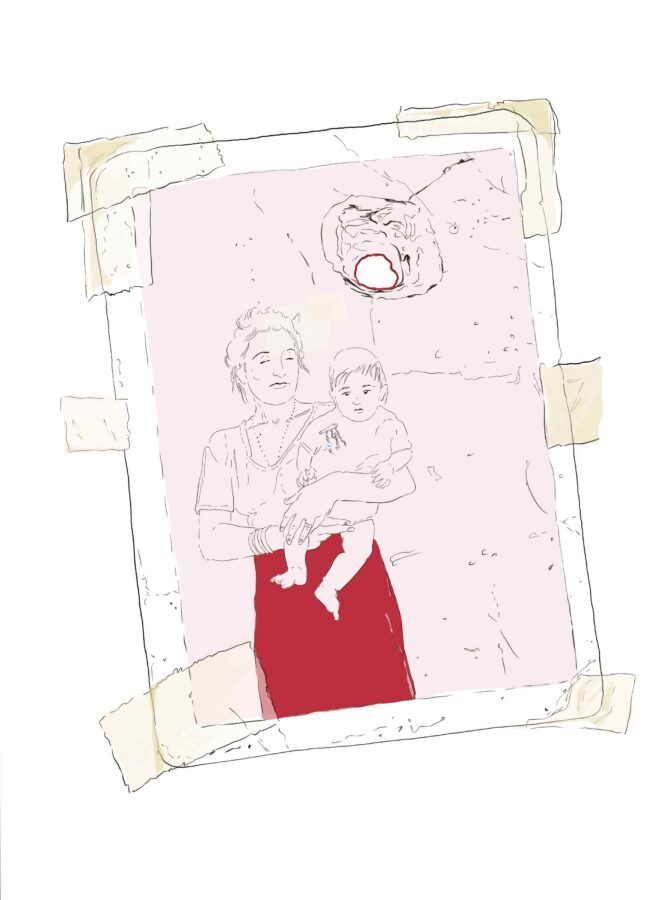

I remember the day my grandmother visited us from her then-occupied southern village and hung a blue glass amulet by the door, an eye to protect us from evil and envy.

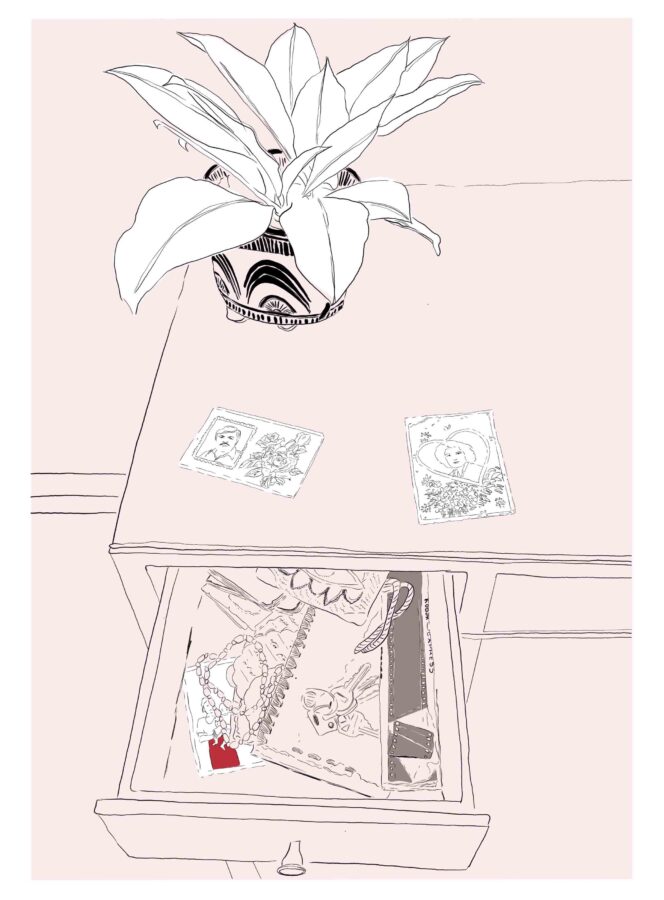

The maps have no chaos, no noise, no scent, no dust. Only outlines and coordinates. And still we hold onto what reminds us that we are not simply collateral: a photograph tucked in a drawer, the shape of a child’s face, a charm pinned to her chest. This is the image I keep returning to. Not the drone, not the bombing, not the map, but the amulet. Its protective power carried not in superstition, but in the accumulated wisdom of grandmothers and those who knew how to survive and had survived before.

* Amid the ongoing Israeli aggression on Lebanon since October 7, 2023, which escalated in September 2024, the Israeli army’s Arab media spokesperson, Avichay Adraee, began using social media platforms to issue evacuation threats in the form of maps and coordinates of targeted buildings—often after midnight, with extremely short deadlines—after which the Israeli air force would launch aerial attacks on densely populated residential neighbourhoods. These threats came at times when many residents were asleep, offline, or not following the news directly.

Note

This visual piece was originally published in Arabic on Khatt 30, on April 22, 2025. Khatt 30 is a platform for written and visual storytelling exploring everyday life, memory, and place across the geographies of the 30th parallel. You can consult the original version here: حين تنكسر النظرة