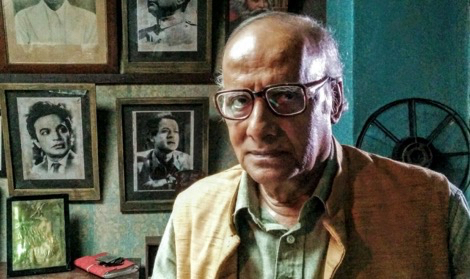

Cinemawala

An aging movie theatre owner in a small town near Kolkata, India, is forced to send his dreams up in smoke as new technology and morality takes over (Cinemawala, Bengali feature film, 2016), while a group of talented musicians in Lahore, Pakistan, almost all senior citizens, whose careers were crushed when Zia-ul-Haq’s regime (1977-88) supressed the arts, are given a way to renew their passion and go global with an innovative, hybrid form of music that combines Western Jazz and Hindustani classical (Song of Lahore, Urdu, Punjabi, English documentary, 2015).

Yet, in nearby Karachi, Pakistan, we see impoverished street children, some of whom come not only from marginalized, but also most likely abusive families, up-close and personal, in a way that I have never before seen in a documentary film (These Birds Walk, Urdu documentary, 2012). We are right on the spot, caged in with these children, in a barebones institution run by the Edhi Foundation, watching them, the feisty protagonist, Omar, in particular, crossing over from cruelty, bravado and a make-believe machismo to total vulnerability, religiosity and even playfulness and camaraderie.

These birds walk

The 2016 edition of the South Asian Film Festival of Montréal (SAFFM) presented by the Kabir Cultural Centre transported 100s of viewers who packed the auditorium on a promised, cinematic journey across this complex and compelling subcontinent, with 17 films spread over a weekend (November 4-6, 2016) that came from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and beyond, capturing, as it did, stories from the South Asian Diaspora as well.

The subjugation of women and class oppression were strong themes and the omnipotent yet layered gender oppression that cuts across social class in South Asia came through persistently. The opening short feature, Mala, (Bengali, English, Hindi, 2016) for example, showed how a privileged, well-educated young girl with dreams of working in Cinema was expected to marry and settle down with a foreign-educated “boy”, with a coveted corporate job. Why? Because. Her father was retiring soon, her elder sister had married 10 years ago and had had a son, were among some of the reasons given by her strong, but conventional, mother.

While Mala came across as somewhat stilted and formulaic, Angry Indian Goddesses (Hindi, English, 2016) flowed naturally, balancing a range of emotions and humour with complexity and character development (not easy to pull off given an ensemble cast of 7 women actors). In a clip Director Pan Nalin sent to the SAFFM for this opening feature film he said that the actresses had made a significant contribution to the script, dialogue, and their roles, during the filming.

Here again we see educated, middle to upper-middle class, professional women (save the servant girl, also a strong character) whose lives are systematically marked and marred by patriarchy. The endemic, women-focussed violence around them eventually informs the actions of the Angry Indian Goddesses as well. I read some criticism of this film online but I did not find it convincing as the film works overall. Not to mention the importance of portraying female friendships on-screen, definitely not common in Indian cinema. The film ends with a potent message: everybody needs to collectively take a stand against female oppression.

The message of female solidarity echoed again in Threads (Bengali, English, 2014), a film set in Bangladesh. There is a middle-class, artistic, real-life heroine, Suraiya Rahman, in this documentary. She is rather strict and conventional as a leader, yet also caring. She not only makes it possible for a group of destitute women to earn a decent living, but also ends up empowering them. Rahman’s dazzling design skills and seemingly boundless creativity are displayed on screen in the form of Kantha embroidery tapestries that reflect historical, mythological as well as domestic and everyday themes, and which, like the music captured in Song of Lahore, travels to different parts of the world, including making it into prestigious museum collections.

I found this film gorgeous. Rahman’s life had many ups and downs, but her art was incredibly uplifting; she lived for and through it. As striking is the fact that the disadvantaged women who worked for her became expert embroiderers, lifted themselves out of poverty and gave their children an education and a better future. We also see them confidently taking care of the business in the last part of the film as Rahman retires. Bravas!

Suraiya Rahman and the women who worked for her were Muslim, but this did not hold them back. Miya Kal Aana (Urdu, 2016, Mister Come Tomorrow), a feature film set in an Indian Muslim, small-town milieu, on the other hand, portrayed utter female subjugation, indeed invisibility. It lay bare and condemned the retrograde, Sharia practice of “Halala” (possibly a perversion of the original, traditional practice) as it manifests in India. If a husband says talaq (I divorce you in Arabic) three times to his wife, the divorce becomes legal. If he wants to remarry her, she must first marry someone else. After that marriage is consummated the second husband must divorce her as well. Only then can she remarry.

Blouse

In contrast was Blouse (in a Hindi dialect, 2014) a charming, comic, short feature set in small town, Hindu India. The two women in the film are housewives but they are not under their husbands’ thumbs. Their husbands are portrayed as decent, bread earners who love and respect their wives. Whew! A breath of fresh air. (A blouse is the upper garment worn under a sari.)

There were other honourable male portrayals. For example, in These Birds Walk we see Abdul Sattar Edhi, the founder of the Edhi Foundation, who has won the highest awards for his humanitarian work, and, on another scale, Asad, the young driver who works for the Foundation and fulfils his difficult task of driving the runways and corpses home and picking up sick people in his van, with consummate humanity.

The intersection of gender and class oppression was effectively portrayed in the short feature, Class (Marathi, Hindi, English, 2016), showing the plight of a female, domestic servant who is constantly berated by her educated, middle-class mistress, but who finally gets her sweet revenge by teaching herself to read and write.

Two Girls

Then there was the in-your-face and rather strident, Two Girls (Malayalam, 2016), by first-time filmmaker Jeo Baby, which succeeds overall in showing the systemic nature of oppression despite some awkwardness and raw edges. This film also takes us to the countryside, this time in the South Indian state of Kerala, where feisty Achu and flighty Anagha, the former poor, the later middle-class, form a tight, schoolgirl friendship.

Achu is constantly inundated by messages of “how a girl must behave” even as rhetorical slogans put out by the government about girl child and women’s empowerment also permeate her social space. Two Girls portrays the authoritarian education system, based on rote learning, as one more system of oppression, though it does show one child-friendly teacher.

The film, which seems to have had financial support from individuals, keeps us engaged in the lives of the two girls, Achu in particular. The most effective scene shows the normally smart-lipped Achu becoming intimated and afraid. But the ending sees her rising to strength and rebellion again. I heaved a sigh of relief, but wondered what the future might hold for her, as indeed for the divorced and forcibly married off woman in Mia Kal Aana or even Mala and the Angry Indian Goddesses, or the street children in These Birds Walk.

A film festival that has you pondering and worrying over the fate of people portrayed in the movies shown can be deemed a success. What do you say?

The films I saw did not provide facile solutions to the many problems they brought to light, rather, they scattered important questions like so many birds in flight all over the South Asian sky. I left admiring and applauding the courage of all these offbeat filmmakers and their crew, all of whom had chosen to engage, and passionately, in the art and craft of filmmaking with a purpose.

Did women make some of the Festival films? Yes, 5 out of the 17! In all there were 6 women directors as two made one movie. This list includes award winning Pakistani-American director, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy (co-director of Song of Lahore). Also a couple of the films had female producers, and likely a few more had female film editors.

Need I say more?

Extremely balanced and very clear and focussed review of this festival….On a city full of great festivals here in Montreal … these views speak a lot to audiences and gives them the tools to look at the smaller but important fringe festivals to watch out for….in this case it highlighted the content, the issues and the courageous filmmakers from perspectives of gender, and the delicate balances in emerging south asian societies…… thank you!