1. Tradition

NANA PEAZANT (narrating)

“In this quiet place, simple folk knelt down and caught a glimpse of the eternal.”

(from the screenplay)

Traditions can be looked at as auras of history. Specific traditions associated with individual families are formed by memories but change with time. What was originally shared and memorialized becomes increasingly mystifying, even to descendants within a group, as over time the initial reason for the creation of the tradition is forgotten or just partially retained. Versions of the original details are changed according to new perspectives, different values, or deep emotions felt by later generations eager to tell in an invigorated, dramatic way what they remember.

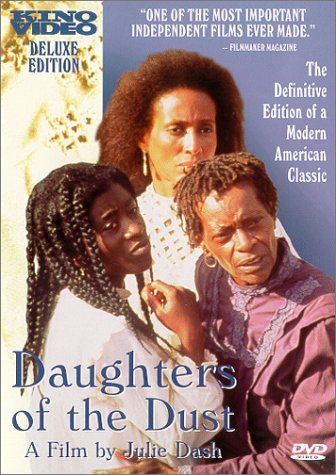

In Julie Dash’s 1991 film, Daughters of the Dust, the Peazant family, whose members feature in the film, have unique traditions formed by their isolation, because they have lived on a sea island offering little contact with others. They formed their tradition of cultural practices based on memories of their ancestors, certain Ibos whose descendants became Gullahs, or Geechee.

The memories that make up a tradition can be as small as a piece of jewellery or a recipe for red rice. The details are beloved and are never considered trivial to the people whose traditions they helped form. They can be symbolic as well as instructive, as were the indigo stains left on Peazant women’s hands as they worked on indigo plantations. Or, deeper still, it could be a Gullah tradition that preserved the legend of the Ibos, their ancestors who rebelled against being brought to the Caribbean and then to the Sea Islands to work under slavery. Gullah lore describes the Ibo Landing inlet where proud Ibos were said to walk on water or develop wings and fly back to Africa, or commit suicide by diving into the sea, rather than submit to the indignity and injustice of slavery. Some chose, however, to stay in order to survive.

Storytelling that passed down knowledge from generation to generation of the Ibo act of resistance became widespread, part history and part mythology, and many a storyteller has been moved to re-create its lore, claiming one inlet or another as “the real Ibo Landing.”

Julie Dash has enlivened the tradition by creating her tale, in film, of Peazant family members who came together from near and far on August 19,1902 to reach a joint decision on whether or not to leave their island, possibly for good, and migrate north for the sake, once again, of sheer survival. Times had changed and opportunities to make a living and gain an education were where industry was growing, in the big cities up north.

In making her film, Julie Dash has acted as one of the griots, traditional storytellers of her culture, narrating through cinematic poetry as a way to preserve history in the face of change. It was a feature film not welcomed at first by Hollywood, which was a rejection that could have prevented the making of the film at all. That is a story in itself of struggle and is told in her book, Daughters of the Dust: The Making of an African American Woman’s Film by Julie Dash, with Toni Cade Bambara and bell hooks. It also includes a commentary by Greg Tate (African American columnist, author, and musician), as well as the screenplay, two family recipes very typical of Gullah culture, and a brief list of Gullah translations.

2. Beyond the Pale

A pale, ghetto, favela, or neighborhood across the tracks, is not settled exclusively by realty-market forces; it is often created by laws, racially or religiously targeted, and policed by selective enforcement of those laws according to stereotypes. Forming black ghettos has been a phenomenon initiated by fear. The rich fear the black poor without knowing much about them, and, moreover, they do not want to know much about them. Hence W. E. B. Du Bois’ concept of black folks’ double consciousness, knowledge of matters both black and white, acquired in their capacities as caregivers and hired hands whose work is to minister to all sorts of needs of the wealthy.

Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust was ghettoized by Hollywood’s incomprehension of it when she tried to raise support for the creation of the film, then again for its screening at festivals after it found funding by other means, then for commercial screenings through distributors and for its marketing to the public.

As Toni Cade Bambara puts it in her Preface to Daughters of the Dust [the book], the motion picture industry “invisibilizes” cultural workers from Chicana/o, Native American, Asian American, Pacific Islander and African American communities. The list gets longer and the issues increase as international filmmakers in Africa, China, Japan, South Asia and the Middle East produce their own films for export. The taste of U.S. audiences for foreign films, even of European origin, diminishes as soon as subtitles appear. Those films are usually relegated to art theaters with a smaller seating space.

Bambara tells us, “Dash’s decision to cast her film with the USA Independent Black Cinema Movement calls our attention to her capsulization of film practices developed since the 1960s.” This path, especially focused on black women, was Dash’s act of going beyond the economic and psychological Hollywood-created Pale to which filmmakers, especially women filmmakers of color, were and still are confined. Sometimes those boundaries were not even articulated by prospective producers to themselves, much less to the filmmaker. They were taken for granted as a barrier against that which is automatically unsuitable.

“Hollywood studios were generally impressed with the look of the film,” Dash comments in Daughters of the Dust [the book], “but somehow could not grasp the concept. They could not process the fact that a black woman filmmaker wanted to make a film about African American women at the turn of the 19th century — particularly a film with a strong family, with characters who weren’t living in the ghetto, killing each other and burning things down. And there weren’t going to be any explicit sex scenes, either. They thought the film would be unmarketable,” she said.

“I always knew,” she wrote,” I wanted to make films about African American women. To tell stories that had not been told. To show images of our lives that had not been seen…

“I was told over and over again that there was no market for the film … I was hearing mostly white men telling me, an African American woman, what my people wanted to see. In fact, they were deciding what we should be allowed to see. I knew that was wrong.” (Daughters of the Dust [the book]

Those were the walls of unawareness, incomprehension, fear, and possibly even repulsion that contributed to Hollywood’s reticence to accept Dash’s film. They did not believe it could appeal to large audiences. They miscalculated.

3. Beauty

Daughters of the Dust ‘s strengths were hard to arrange into categories, as its characteristics were far from conventional. The film invited viewers to consider, possibly for the first time, Gullah women and the cultural inheritance they are entrusted to preserve. It was not a documentary, an educational piece of ethnography, but in bell hooks’ words, in dialogue with Julie Dash, a “work set within a much more poetic mythic universe” (Daughters of the Dust [the book]).

There was a mysterious quietude about the sight of Peazant family members strolling meditatively along their endless-seeming beach front or frolicking with abandon on the strand, completely at home. The idea of black farmers and fishermen in 1920 being at ease, wearing their formal, handmade finery on their special-occasion day, brought an intriguing contrast of refinement seen against the barrier island’s coastal ruggedness.

Arthur Jafa’s stunning cinematography was full of hypnotizing visual poetry and was accompanied by subtle music (a harp rippling or a delicate flute blending with rhythmic hand beats on talking drums). As one group of family members or another came into view, a variety of atmospheres was revealed in the background: ocean, beach, woodlands with trees unique to the marine setting, the swamp with its Ibo relic, and finally the river inlet.

One of the most striking, quintessentially mythic images in the film is the sight of that relic, a wooden statue, male figurehead from a slave ship (perhaps representing an escape in itself from the “Wanderer” that brought the last captured people to Ibo Landing). The figure floats slowly, supine, through the water. The Peazants would see it in different parts of the swamp, and in different lights, any time they strolled beside the water or walked in it, shallow as it was. The figurehead would be permanently staring at the sky, motionless yet seemingly impelled to drift, borne along by time, a constant memory to the Gullahs of their Ibo heritage.

There is, too, throughout Daughters of the Dust a physical beauty of the Peazant women, each unique, with different skin tones and styles of how they wear their hair, how they dress, and how they carry themselves with a graceful air of self-possession, something that runs in the family. We see them walking in a line down the beach, picnicking, standing in a circle as they share a secret. We see them in fleeting close-ups as they move through the woods or lean against a tree. We see them in moments of stillness, observing a spouse a few feet away, and we often see Eula in three-quarter view. She is the young mother-to-be who has married Eli Peazant, and whom her sophisticated relative, Yellow Mary, refers to affectionately as a truly “back-water” Geechee girl. In Eula’s close-ups we see an exceptionally expressive face, her eyes full of urgency and her mouth tightening as she speaks with all the eagerness and sincerity she feels.

The aesthetic elements of the film aren’t discrete phenomena, as singled out here. They are a whole that has been elegantly woven together. One of its threads is a blue indigo theme, with flashbacks to a time when Gullah women pounded indigo plants into blue paste that plantation owners would have workers make into indigo fabric dyes. The matriarch, Nana Peazant, wears an indigo blue dress, and symbolically Julie Dash shows Nana with hands dyed indigo blue. We see, too, Eula’s unborn child (before she is actually born) as a spirit already taking her place as the family’s newest member, dressed demurely as she soon will be in life, with a blue ribbon in her hair.

Other references to Peazant textiles are quilts made by the women and seen frequently as young and old stir under quilted covers whose close-ups look like undulating mounds, soft squares that mimic ocean waves.

The clothing worn by both the men and women exhibit a typically 19th-century sense of finesse, the women in long dresses with various decorative, white, criss-crossed appliqués worn at the neck and halfway up their brown arms where they reach billowing cotton sleeves. Simpler versions of those long dresses are worn by the girls, but with bits of intricate embroidery added and simpler versions of the men’s formal clothing are worn by the boys, well tailored suits with white, collarless shirts and no ties under either jackets or vests.

On that day in 1902, the Peazants’ story takes place between two bookends as it were. First is the arrival of a barge steered slowly through the inlet by men using stripped wooden paddles, splashing as they move closer to Ibo Landing. Arriving are the glamorous and somewhat wealthy Yellow Mary and her “even yellower” companion, Trula. Soon they are joined for a short ride by the photographer, Mr. Snead, and Viola Peazant, who has hired him to apply his advanced technological skills with the camera and all its paraphernalia to photograph the family and memorialize the day of decision-making when they will determine who shall migrate north and who shall stay behind.

The other bookend is the departure of most of the Peazants, as they are being rowed out of the inlet slowly. They have a similar barge and similar boatmen, but now there is the air of a processional, a journey more than to the North but to another realm, the Unknown. Those who will stay behind look on with the deepest apprehension and resignation as they watch their loved ones leave, possibly never to return.

Only one young Peazant is no longer present at the departure. She is Iona, who has eloped before anyone can stop her. Haagar, her mother, has tried, but Iona has ridden away on horseback with St. Julian Last Child, a lone Cherokee survivor on the island after the rest of his tribe has been forced to migrate to Oklahoma. Now he and Iona have mutually fallen in love, and with their elopement a new link in the chain of tradition has been forged — one of transcultural exchange and harmony, it is hoped. (See Daughters of the Dust [the book].)

All of the beauty of the film was finally recognized when Julie Dash attended a PBS (Public Broadcasting System) retreat in Utah and met the director of program development for American Playhouse, the group that agreed to provide most of the funding for Daughter of the Dust. They had the means to enable shooting to begin and to see it through to most of its completion.

Dash’s step-by-step, matter-of-fact descriptions in her book of how all the obstacles to making the film were overcome, and of the patience it took to reach her goal, reveal the tremendous dedication to the story she wished to tell and to the actors and crew she had assembled. It exhibited amazing persistence on her part, as it had taken years of creation from a roughly hewn concept, to ten years of research, to fundraising, to the first shooting, then five years more of shooting and additional fundraising until the film made its debut at the Sundance Film Festival in Utah, in 1991.

Its feature-film opening at the Film Forum in New York took place on January 15,1992. It sold out every show of a long run. Julie Dash was the first black woman to accomplish filmmaking at this level. Daughters of the Dust became a classic narrative film, garnering many awards along the way, and after 25 years it has been completely restored for new generations to see.

In one of their many conversations after Yellow Mary’s arrival at Ibo Landing, Yellow Mary told Eula where she and Trula would head when they went north. It was Nova Scotia. “Nova Scoria will be good to me,” Yellow Mary mused. Something, however, intervened. For the sake of newcomers to Daughters of the Dust, what that was shall be for them to witness onscreen for themselves.

Many black citizens of the United States, mindful of their history in general and of the Great Migration north from the southern states, which was in full swing by 1910, know something of the concentration of black immigrants settled in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick but not the full story by far. According to historical records, the first black person to arrive in Nova Scotia did so in 1604, and there have been numerous waves of black settlement there ever since (one during the War of 1812, and another, for instance, with the migration of many people from the Caribbean islands circa 1950.)

Yellow Mary can be inferred from the screenplay to have had a large measure of black cosmopolitan traits at heart, which Eula seems to draw out of her with wide-eyed curiosity. One of their conversations in Daughters of the Dust seems to go against the stereotype of black Canadians as simply black folks who crossed the U.S.-Canadian border and brought an unchanging U.S. culture with them, without the transcultural changes that migrations entail. This afterword celebrates in a small way, via the beginnings of a list centering on nine black women filmmakers, some of those changes that black Canadian film culture has developed with U.S., British, and Caribbean infusions, but combined with a many-stranded European and Indigenous Canadian cultural history plus growth uniquely its own.

AFRICAN CANADIAN WOMEN FILMMAKERS

CHRISTINE BROWNE (b. 1965 in London. Kittitian Canadian)

KAREN CHAPMAN (2nd generation Canadian – British Columbia. Afro (Guyanese) and Indo-Caribbean heritage)

MARTINE CHARTRAND (b. 1962 in Montréal. Haitian Canadian)

JENNIFER HODGE DE SILVA (b. 1951 in Montréal. African Canadian)

ALISON DUKE (b. in Canada, lives in Toronto. African Canadian)

SYLVIA HAMILTON (b. Beechville, Nova Scotia. African Nova Scotian)

STELLA MEGHIE (b. in Toronto. Jamaican Canadian)

CLAIRE PRIETO (b. 1945. Trinidadian Canadian)

FRANCES-ANNE SOLOMON (b. 1966 in London. Trinidadian heritage, Caribbean British Canadian)