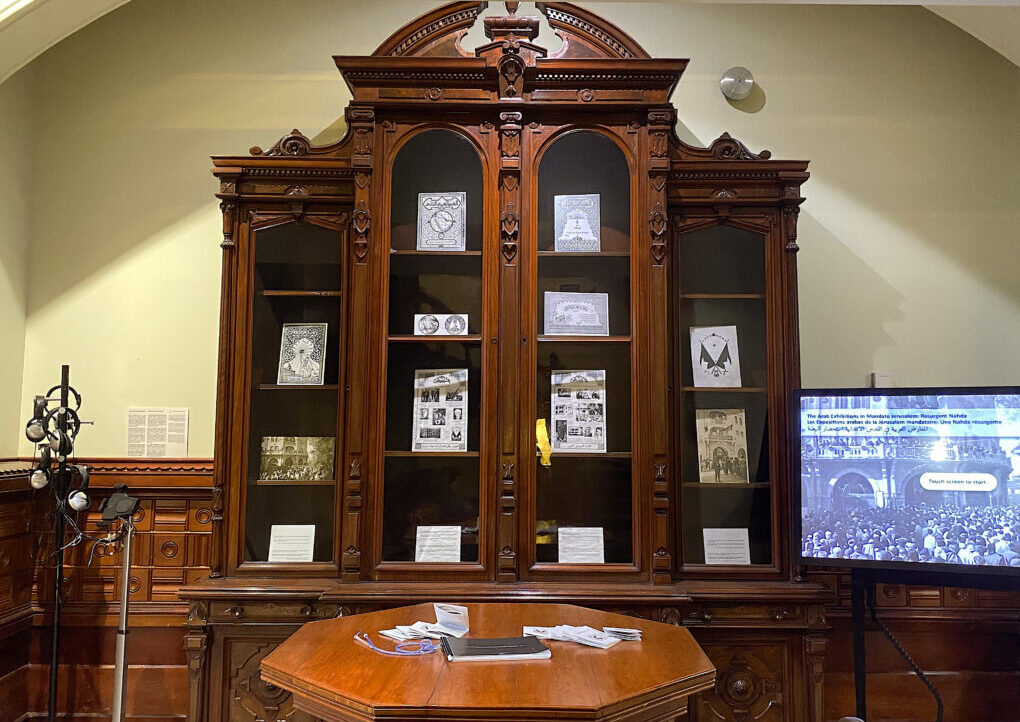

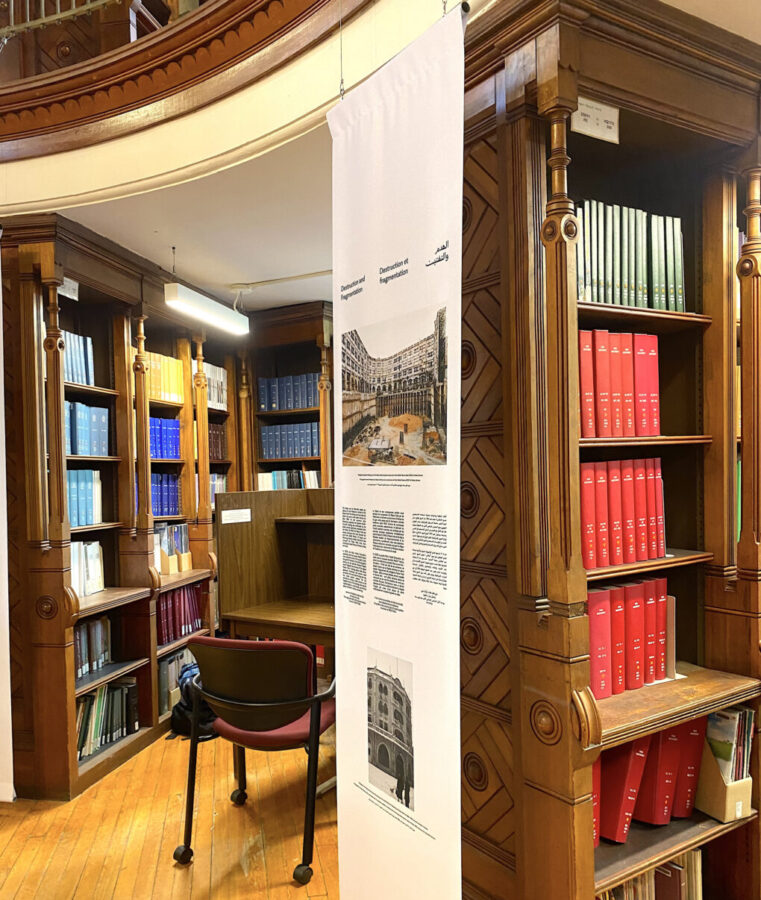

In the Islamic Studies Library at the heart of McGill campus, the public was invited to explore a beautiful, partly interactive exhibit titled “The Arab Exhibitions in Mandate Jerusalem: Resurgent Nahda,” curated by Palestinian historian and architect Nadi Abusaada and architect Luzan Munayer.

Accessible in French, English and Arabic, the “Resurgent Nahda” (renaissance) ran from Sept. 5, 2024 until June 12, 2025. The interactive component included a touch screen programmed to provide immersive geographical imagery to viewers, enabling them to embark on a historical virtual tour to learn about three prominent structures in the City of Jerusalem in 1930.

The exhibit was the inaugural launch for Maison Palestine / Dar Filastin, a not-for-profit organization founded in early 2023 in Tiohtià:ke (Montréal). Maison Palestine’s principal mission is building a permanent educational and cultural space rooted in Palestinian history—past, present and future—in Tiohtià:ke.

During my in-depth interview with founders Dyala Hamzah and Nyla Matuk, they relayed how their identities as Palestinian women have played a critical role in the development of Maison Palestine, an organization dedicated to featuring and centering Palestinian knowledge and art produced both in Palestine and by the diaspora, in efforts to preserve and build on a collective history.

“Everything is desperate but everything is also possible.”

Dyala Hamzah

In our interview, the founders emphasized the important role of Palestinian knowledge and the predicament of its transmission in a context of pervasive Zionist ideology in academic settings. Dyala, a professor of Contemporary Arab History at Université de Montréal, calls attention to how “academic institutions are now playing an active role in disinformation about Palestine. What was simple misinformation before is now actively thriving in academic settings, leading to repression by a hegemonic settler-colonial ideology.”

In many ways, Maison Palestine is a response that challenges “The History,” curation of the archives, and historical knowledge that privileges Zionism as a hegemonic political ideology, overwhelming even academia. Thus, re-learning and re-envisioning the past, present and future of Palestine is the fuel that runs the engine of Maison Palestine.

Maison Palestine is forefronted by Nyla and Dyala, both esteemed intellectuals in their respective fields who have devoted immense energy to realize Maison Palestine, beginning with the “Resurgent Nahda” exhibit presented to a Western audience as well as to the Arab diaspora of Canada. The idea of inaugurating Maison Palestine with “Resurgent Nahda” was inspired by Nyla’s visit to Ramallah in 2022 after she chanced upon Nadi Abusaada’s exquisite exhibit at the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre.

The Maison Palestine team was struck by the material reality of the Arab Exhibitions and the phenomenon of a “Resurgent Nahda” in the 1930s, a major political and cultural moment, a crossroads during the British Mandate years. Moreover, for Maison Palestine, presenting The Arab Exhibitions to a modern-day Canadian audience encapsulated the essence of their mission: unearthing Palestinian knowledge that has been buried. Presenting “Resurgent Nahda” to a Western audience is urgent and timely; Maison Palestine strives to be likewise powered by the past and the present of Palestine in order to imagine its future—“Everything is desperate but everything is also possible.” (Nadi Abusaada)

For Maison Palestine, presenting The Arab Exhibitions to a modern-day Canadian audience encapsulated the essence of their mission: unearthing Palestinian knowledge that has been buried.

To understand the full implications of this multi-dimensional exhibition, one must consider it as a political undertaking by Maison Palestine and Nadi Abusaada—and this undertaking itself is part of a larger political movement, where forms of historical narration of Palestine as a distinct nation are being reinterpreted and are actively disrupting our preconceived and embedded notions.

A conversation between exhibitions, across time and space

As I walked through the exhibit, Nadi Abusaada’s assertion that Palestinians were no mere passive subjects of colonialism schemes for Jerusalem’s future rang loud through my head… And yet simultaneously, a dual consciousness began to take hold, with the realization that what I was being presented were the roots of a hundred years of brutal colonization and genocide in the making. This awareness would not have been possible if not for the archival regeneration undertaken by Abusaada and facilitated by Maison Palestine. Nadi Abusaada and Maison Palestine have worked across time and space to create powerful and dynamic new possibilities for reckonings of Palestinian history, in Canada and beyond.

This exhibit exemplifies the ongoing suppression of information about—and censorship of—Palestine.

This exhibit exemplifies the ongoing suppression of information about—and censorship of—Palestine. Although “Resurgent Nahda” is an exhibit of historic events, neither provocative nor politicized for the present, Maison Palestine faced a myriad of obstacles and rejections as well as disinterest from the Montréal community, when looking for venues to host the exhibit. A battle not for the faint of heart.

One example is a prominent educational institution, Université de Montréal, which initially accepted and then cancelled the exhibit a month before the launch on the grounds that it presented “security risks.”

After October 7th, when Israel embarked on a full-scale genocide in Palestine while the West began full-scale complicity in supporting the Israeli regime in every sector, the realization of this beloved “Resurgent Nahda” exhibition took immense efforts in all dimensions, including the realm of imagination. As shipping from Palestine was no longer possible, the exhibit transitioned to a print exhibit without artifacts and tailored to fit into the beautiful yet unconventional and peculiar rooms of the Islamic Studies Library.

The team at Maison Palestine worked with fierce advocacy, putting in long days of planning and intense overseas coordination sessions with Nadi Abusaada (in Zurich), Luzan Munayer (in Jerusalem), production assistant Mayyasah Akour (in Montréal) and the Islamic Studies Library staff prior to the exhibit’s opening in September 2024.

Over 90 years ago, two Arab Exhibitions were held consecutively in 1933 and 1934 in Jerusalem, representing the Palestinian-Arab “Nahda” (renaissance) and showcasing the Arab world’s artisanal, agricultural and economic sectors. The Arab Exhibitions in the Palace Hotel exhibited paintings, craftsmanship and calligraphy pieces. A prominent feature of these exhibitions was to platform Arab-led agricultural and industrial developments that were rapidly occurring despite heavy European colonization throughout the region and the developing Zionist settlements in Palestine.

Maison Palestine’s founders were taken with the significance of The Arab Exhibitions and the idea of a Resurgent Nahda as a timely and timeless movement that occurred in Mandate Palestine, reflecting a moment when Palestine both geographically and ideologically was at the forefront of economic prosperity and invention despite the pressure of the British and Zionist Forces.

The exhibit at McGill offered the viewer an intimate experience of the Arab Exhibitions as a material realization of Arab nationhood, economic prosperity and unity.

The exhibit at McGill offered the viewer an intimate experience of the Arab Exhibitions as a material realization of Arab nationhood, economic prosperity and unity. “Resurgent Nahda” portrays sentiments of a crucial period in Palestinian culture and economic activity in Jerusalem during British colonial rule. A guided journey explores the complex socio-economic fabrics of Mandate Jerusalem in the 1930s, through Two Arab Exhibitions pioneered by founder Issa al-’Issa and The Arab Exhibition Company. Men like Issa al-’Issa belonged to an emerging Palestinian corporate elite in 1920-30 and used the Arab Exhibitions to showcase their economic visions of a Palestinian nation.

Nadi Abusaada set the stage for a historical revival of Palestinian agency during the 1930s by spotlighting the Haram Al Sharif holy site, the Palace Hotel and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. These architectural institutions were prominent Palestinian spaces and hubs of economic and political activity. Each was also a site of resistance during the British Mandate, wherein British policies heavily disadvantaged the Arab population both politically and economically.

The focal point of the interactive component is a map detailing the city of Jerusalem in the 1930s. This tour provides archival information about the three institutions to highlight the reality that Arab Palestine had thriving cultural and political institutions, despite British-Zionist colonial narratives that characterized Palestine as an empty Bedouin society before Zionist settlement. There is an intentionality behind Abusaada’s work that urges the viewer to look beyond current conceptions of Jerusalem as purely a homogeneous and “rightfully” Jewish land.

The focal point of the interactive component is a map detailing the city of Jerusalem in the 1930s.

For example, the Haram al-Sharif is a famous historical site for contemporary Israel; however, during the British Mandate years it was restored by a Palestinian committee after severe damage to the building due to an earthquake. It was subsequently re-purposed as a space for Palestinian artists such as Jamal Badran, who provided illustrations of the Arab Exhibitions.

The Palace Hotel, the venue for the Arab Exhibitions, was built under the auspices of the Supreme Muslim Council by architects Rushdi al-Imam al-Husseini and Mehmed Nihad Nigizberk in an “Arab style.” It was described as one of the most luxurious hotels in Jerusalem. The Palace Hotel was subsequently seized and demolished in 1948 by Israeli forces, its furnishings looted or auctioned off, and in 2008 it was bought and remodeled by the Hilton Hotels Corporation and IPC Jerusalem Ltd.

Anti-colonial resistance and a right of resurgence

To fully appreciate the importance of the Two Arab Exhibitions, both in their material and symbolic implications for Palestinian society, it is critical that they be contextualized within a struggle against colonialism throughout the Arab world. Abusaada does not shy away from this task—he weaves the Exhibitions into the broader political landscape of Mandate Palestine in the 1930s.

According to historian Rashid Khalidi, the British Mandate for Palestine (1918-1948) and the larger British-Zionist project were the catalyst for the systematic dismantling of Indigenous Palestinian society.

According to historian Rashid Khalidi, the British Mandate for Palestine (1918-1948) and the larger British-Zionist project were the catalyst for the systematic dismantling of Indigenous Palestinian society. Abusaada recalls how British authorities ratified Palestine for the “establishment of a Jewish National Home,” privileging the Zionist campaign economically and politically while ostracizing and disempowering the Arab population.

Under the Mandate, binary Arab and Jewish socio-economic systems emerged under one unified geopolitical territory. However, as Zionist settlements expanded into Palestinian territory, so did their economic and political power, establishing separate political, military and financial institutions, essentially operating as a “state within a state” while the Arab-Palestinian majority continued to be marginalized and displaced.

Thus, the geographical location of the Arab Exhibitions in Palestine added an extra level of significance in terms of anti-colonial resistance. Abusaada presents a timeline that connects the repression that the organizers of Exhibitions faced from the British-Zionist project to heightened tensions between the Arab population and Zionists settlers. This provides context notably for the Buraq Revolt of 1929 and the Great Revolt of 1936.

Nadi Abusaada maps the Arab Exhibitions as a right of resurgence onto the socio-economic fabric of Palestine. In 1933 and 1934, the Exhibitions functioned as a symbolic and material realization of Arab national identity and economic prosperity, but were also inseparable from Palestinian defiance and resistance against the Zionist occupation.

Abusaada also highlights the politicization of geographic location, as Jerusalem was not intended to be the site of the Arab Exhibitions. The original location was to be Jaffa, as it was in closer proximity to the Levant Fair, a large-scale Zionist project in their new Tel Aviv colony. Issa al-‘Issa intended to host the Arab Exhibition to counter the Levant Fair’s influence and to align with the Arab Executive Committee’s anti-Zionist policies. However, the British administration did not approve the constitution plans in Jaffa, as the exhibition “excluded the Zionists.” In the wake of this defeat, the Arab Exhibitions Company relocated the venue to the Palace Hotel, recently built by the Muslim Council in Jerusalem.

The establishment of the Arab Exhibitions was critical for the articulation of a Pan-Arab national identity. It fostered a space of transnational commercial exchanges and dissemination of knowledge and expertise between Arab countries within the context of the British and French colonization that had fragmented, if not paralyzed, the Arab geopolitical landscape.

The establishment of the Arab Exhibitions was critical for the articulation of a Pan-Arab national identity.

The Exhibitions took place when Palestinians were their own national identity within the changing socio-economic fabric of Palestine. Abusaada does incredible work informing the viewer how transnational links in the Arab world facilitated the realization of the Arab Exhibitions in Palestine under the guise of national production among Arab nations, through economic bonds.

During the 1920s and ‘30s, worldwide exhibitions such as the Paris Colonial Exhibitions (1931) conveyed one-dimensional colonial representations of Palestine as a “holy land,” Arab-style architecture contrasted with modern Zionist developments such as factories. This image served British-Zionist interests. Issa al-‘Issa’s vision was informed by this frustrating narrative; the Arab Exhibitions represented a Palestine that was no longer seen as simply a “holy” space or structure to facilitate Zionist developmental aspirations in universal colonial spaces. His approach was cemented after his visit to the Iraqi Agricultural and Industrial Exhibitions in 1932. Al-’Issa met with King Faysal I and prominent Arab businessmen there, and was able to gather enough sponsors to establish The Arab Exhibition Company as a private shareholding company in 1932.

Two months after the First Exhibition and leading up to the Second, the Arab Executive Committee, the supreme representative body for Arabs in Mandate Palestine, called for a national strike to boycott British policies on Zionist settlement in Palestine.

The First Arab Exhibition was largely successful. Attendees traveled from various parts of Palestine and the Arab world. Soon after, in 1934, the Second Arab Exhibition was held to display arts, crafts and industries from the Arab world, including Egyptian participation. Two months after the First Exhibition and leading up to the Second, the Arab Executive Committee, the supreme representative body for Arabs in Mandate Palestine, called for a national strike to boycott British policies on Zionist settlement in Palestine. Major demonstrations took place in Jerusalem and Jaffa, spreading to other urban areas. They were met with violent repression by the British Police Force in Palestine. This episode of brutality foreshadowed further violence enacted by Zionist forces during the 1936 Great Revolt in Palestine.

The historical records of Arab-Palestinian civil society during the Mandate years are largely fragmented, and the Arab Exhibitions are a testament to this fragmentation. Despite the momentous historical significance of Pan-Arab unity and transnational participation during a time of colonial rule, the Exhibitions remain largely erased from dominant archival records of Jerusalem’s history since Zionist occupation.

Nadi Abusaada’s task was not simply an archival project but a decolonial undertaking at its core, re-centring the discourse through a reconstruction of Palestinian and Arab history.

Nadi Abusaada’s task was not simply an archival project but a decolonial undertaking at its core, re-centring the discourse through a reconstruction of Palestinian and Arab history. He sources pictures, maps and archival information from the Palestinian Nahda to breathe life into the two historical Arab Exhibitions. Their resurgence through this exhibit in Montréal creates a unique immersive experience, delivering a vivid experience of a different, less-known Jerusalem with a strong tradition of Palestinian presence and within a history that has been continually erased and wracked by genocide due to Zionist colonization.

The exhibition itself demonstrates the ongoing repression of information and visibility afforded to Palestine. Although politically significant, “Resurgent Nahda” is neither proactive nor “contemporarily political.” Yet some readers may find it shocking or perhaps infuriating to find out that it took a battle not for the faint of heart to present this exhibit in the locality of Montréal.

Maison Palestine faced salient political repression and rejection from the Montréal community when looking for venues to host “Resurgent Nahda.” To emphasize: the fact that an archival exhibition was labelled a “security risk” attests to the extreme anti-Palestinian racism that runs rampant in the city. The very existence of the beloved “Resurgent Nahda” exhibition took fierce advocacy, long days of planning and intense overseas coordination with Abusaada and his team in Montréal.

Maison Palestine faced salient political repression and rejection from the Montréal community when looking for venues to host “Resurgent Nahda.”

It is impossible to separate Abusaada’s and Maison Palestine’s “Resurgent Nahda” from the current political moment, as pro-Palestinian activists and scholars argue that the systemic genocide, displacement, brutalization and murder of Palestinian civilians is not in fact a sporadic or contemporary act of state-sanctioned Israeli violence, but part of the ongoing violent historical of erasure of Palestinians carried out by the Zionist entity long before October 7, 2023.

Note

A French version of this piece is available through Histoire Engagée, along with excerpts of Sheida Mousavi’s interview with the founders of Maison Palestine.

Further reading

Khalidi, Rashid. The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917-2017. New York: Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company, 2022. Chapter 1 in particular provides a full insightful analysis of the role of the British in occupying Palestine starting in 1917. Khalidi argues that the British Mandate for Palestine and its full sponsorship of the Zionist project in Palestine marked the beginning of systemic displacement and dispossession of Palestinians from their land.

Abusaada, Nadi. “Self Portrait of a Nation: The Arab Exhibition 1931–34”. The Institute for Palestine Studies (2019), 122–31.