This project helps to create stronger communities, build new forms of solidarity, and exchange perspectives that are often overlooked in mainstream narratives.

The works that follow reflect our personal journeys through heritage, healing, migration, identity and resistance. Whether through scent, sound, colour, or texture, each piece expresses a powerful answer to what keeps us going and invites you to consider your own.

Our Daughters – Sahara Romero

Inspired by the saying, “Hope has two daughters: Anger and Courage,” this artwork merges the power of music and visual storytelling with the emotional forces that drive action against injustice and struggles.

The red ukulele, sculpted with clay faces, embodies the intensity of anger, while the black textured ukulele with its open body symbolizes the courage needed to stand tall and speak out. The heart and flower represent the bravery it takes to open up and voice one’s truth. The flower also honours strong women role models who inspire the next generation with their strength and resilience.

The collective energy of countless female artists, from the music industry to film, continues to spread hope. It is this collective energy that keeps me going.

I’m Sahara Romero, a 21-year-old Hispanic visual artist studying cinema and communication. I was born and raised in Montreal in a family of eight. Growing up, my siblings and I would make small skits with a Hitachi Hybrid camcorder. This was a way for us to bond and express ourselves, and inspired my passion for filmmaking.

My artwork reflects my deep contemplation of humans’ relationships, with one another and with the environment. I tend to be mindful of waste when creating art, which is why I upcycle materials. These interests also led me to find my passion for scenography and develop a strong appreciation for diverse storytelling techniques, including visual, auditory and innovative approaches. @draaa.ca

Healing the spirit – Shayla Chlöe Oroho:te Etienne

Healing the spirit” is an emotional piece about my struggle of connecting with my cultural roots and breaking cycles. Creating this artwork was emotional on its own, and it felt amazing to put my emotions into perspective.

The bear represents my clan and culture, protecting the land around it and myself. The girl in front of the bear is me. Her hair is connected to the ground to represent connecting roots, and her calm demeanour presents confidence in herself and her strength.

The woods are the pines in Kanesatake, surrounding her and illustrating stories of spirits preceding her as well as those succeeding her, whilst also adding a detailed touch to symbolize the Oka crisis, hence the bullet holes. The bullet holes are bleeding as if recent wounds are open.

Kwe, my name is Shayla Chlöe Oroho:te Etienne, I’m 21 years old and I’m Kanien’kehá:ka from Kanesatake. I graduated in June from the visual arts program at Dawson College and I’m currently in the art education program at Concordia University. The media I use are acrylic paint, charcoal, pastels, pencil crayons and graphite on different types of material, such as canvas, paper, fabric and wood.

@orohote_creations

Untitled (watercolour, mixed media) – Jiane Keizha Pau

These circles (or this one circular line) were inspired by the main protectors of Kanehsatake, the pines. Those evergreens (although not shown in this piece) took bullets for the Mohawks during the 1990 Kanehsatà:ke Resistance.

The tree presented in this piece depicts something similar and points again to the importance of nature in our lives. Trees give us life through oxygen, shade, and protection. They can represent growth/self-growth and the development of our kind as more thoughtful and sociable people. The ringlets, inspired by the ridges of a chopped tree trunk that tell its age, can also be seen as the various circles and/or cycles in our lives – like the circle of life or the infinite greatness of the Creator. The canvas has been painted with diluted watercolours simulating tree bark tying the whole tree theme back together. The warm colour pallet is meant to reflect the fall foliage of our region.

My name is Jiane Keizha Pau and I am a Chinese-Filipino-Canadian artist from Montréal. My artwork is heavily inspired by my surroundings and the people I meet. Being a part of two distinct cultures has allowed me to value culture, history, family, and community differently than most. Growing up with nature-loving parents, I learned to appreciate the small things brought on by the Creator. My pieces are all about innovative ideas, colourful palettes, and experimental tactics. I enjoy learning about others and their stories, delving deeper than what society portrays them as. That’s what sparked my interest in this project. I believe in connecting with others, especially those who have amazing stories to tell, because they are the ones who could be truly impacting others.

@specks_in_the_universe

Mahal Kita – Lindsymae Corpuz

Mahal Kita is a piece meant to express the words that I cannot. Meaning I love you in Tagalog, this work is a testament to some of the sacrifices that my parents have made for me and my siblings since immigrating to Canada.

Using multiple mediums and techniques, I’ve pieced together photographs, notes, sketches and pieces of our family’s life to give a picture of how my parents’ hard work and love has paid off.

The film being projected is one of my first short films shot on an old camcorder, and is meant to represent a day in the life of my parents — how they go about their daily lives now, and the mundaneness of it all.

Juxtaposed with the images are audio recordings of conversations I had with them about their past. As viewers, you become mere observers getting a glimpse into their lives. You don’t know who they are or even get to know their names, but for the short 3 minutes, you get to hear them talk all about their hopes, dreams, past and present lives.

“A day in the life: a documentary about immigrant parents” © Lindsymae Corpuz, 2024

Lindsymae Corpuz is a recent graduate of Dawson College’s Cinema & Communications program, currently working at a community centre in Pointe-Saint-Charles. With interests in photography, writing, mixed-media and collecting trinkets from around the world, her passions revolve around creating moments to be shared with whoever is willing to listen. Although she plans on pursuing studies in education with a focus on doing community work, she still wishes to use art as a tool to fight for change and get people’s stories out there.

@lindsymaecorpuz

landscape no.6 & landscape no.7 – Gregory Chae

landscape no.6 is a canvas-mounted sculpture of a human torso made of cardboard and plastic, with two mantis claws protruding from its back, and a curtain draped over its shoulders. It expresses the artist’s relationship with the inevitable transformation of identity through time. White settler colonial institutions exploit the material vulnerability of the peoples they oppress, and uphold a superficial permanence of their reign. Settlers’ landscapes have a famously colonial history. landscape no.6, categorically not a true landscape, interrogates the colonial fear of the mutation of ‘human’ identity (the dismantling and/or reclaiming of colonial categories of human identity), threatening to reveal too much of the oppressor’s own material vulnerabilities. The curtain suggests privacy, with a willingness to reveal, to be proudly a material being, transforming, cocooning, becoming on its own terms.

landscape no.7 is the accompanying piece to landscape no.6. It is a helmet made of cardboard and plastic, with two horns and a spine. In sharing the same materials as landscape no.6, landscape no.7, the mind, works in tandem with its body. The dialogue between mind and body is grounded in the pairing of the two sculptures.

Gregory Chae is a Korean-Canadian student and artist dabbling in performance pieces, sculptures, writing, illustration, and they continue to experiment with various physical and digital media. To further explore their interest in reconstructing narratives and contextualizing identity, they wish to pursue studies of theatre and scene design.

The Essence of Continuity – Seralathen Sivappiragasam

Spices are more than ingredients; they carry stories, traditions, and histories. In my piece, I use spices rooted in South Asian culture to symbolize resilience, heritage, and the sensory connections that sustain us. These elements evoke memories of family meals, ancestral remedies, and the enduring legacies of colonialism, where spices—once sacred and essential—became commodities of exploitation.

The black-painted canvas serves as a grounding space, while swirling patterns represent movement, adaptation, and the evolution of tradition—how cultural practices shift over time yet remain deeply connected to their origins. Scent is one of the most powerful triggers for memory, and incorporating spices was an intentional choice to engage multiple senses, allowing the audience to experience the piece beyond sight. Through sensory storytelling, I hope to evoke empathy, encouraging reflection on how colonial histories, migration, and cultural preservation shape both personal and collective identities.

This piece is both personal and universal, exploring what keeps us going. My sister, the creative force in our family, has always inspired me to embrace artistic expression. Her influence encouraged me to create this work that reflects continuity—honouring the past while embracing the future. Just as my work in healthcare emphasizes resilience and human connection, this piece reflects my belief that creativity and empathy are powerful tools for healing and understanding.

Seralathen Sivappiragasam is a nursing student, storyteller, and lifelong learner with a deep interest in creativity as a means of connection, understanding, and empathy. While his primary background is in healthcare and community work, he is drawn to artistic expression through music, culture, and storytelling. His studies in the Indigenous Studies Major and Nursing at Vanier College shape his perspective on the intersections of art, healing, and identity.

Seralathen’s creative projects explore themes of resilience, tradition, and global perspectives, often inspired by his Tamil-Canadian heritage and his upcoming international nursing exchange in Malawi. His contribution to the What Keeps Us Going project reflects these influences, using spices as a bridge between memory, culture, and the senses. Though still discovering his artistic voice, Seralathen believes creativity exists in many forms and continually seeks ways to integrate it into his work and daily life.

@sera_la_then.mp3

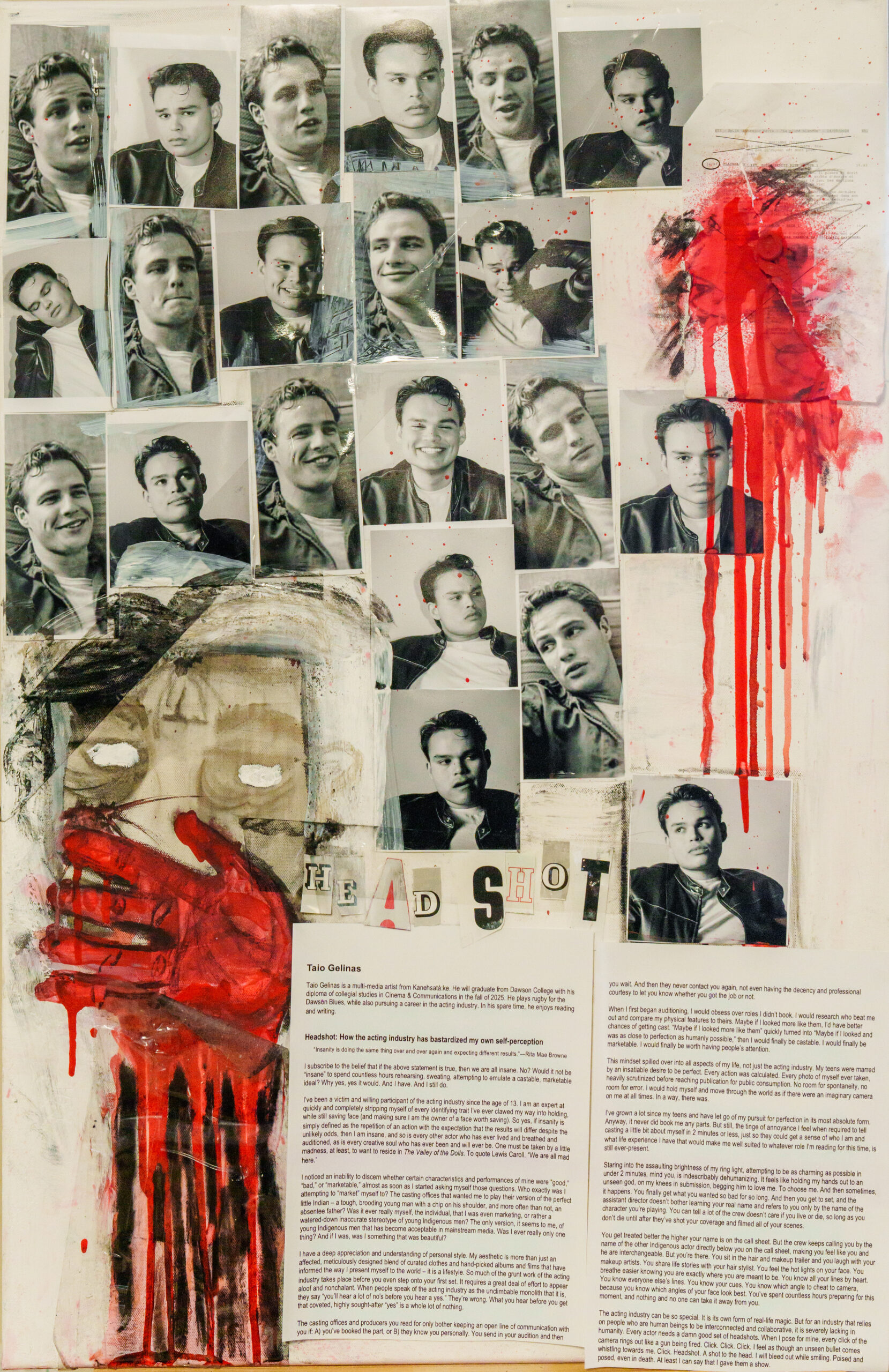

Headshot: How the acting industry has bastardized my own self-perception – Taio Gelinas

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

—Rita Mae Browne

I subscribe to the belief that if the above statement is true, then we are all insane. No? Would it not be “insane” to spend countless hours rehearsing, sweating, attempting to emulate a castable, marketable ideal? Why yes, yes it would. And I have. And I still do.

I’ve been a victim and willing participant of the acting industry since the age of 13. I am an expert at quickly and completely stripping myself of every identifying trait I’ve ever clawed my way into holding, while still saving face (and making sure I am the owner of a face worth saving). So yes, if insanity is simply defined as the repetition of an action with the expectation that the results will differ despite the unlikely odds, then I am insane, and so is every other actor who has ever lived and breathed and auditioned, as is every creative soul who has ever been and will ever be. One must be taken by a little madness, at least, to want to reside in The Valley of the Dolls. To quote Lewis Caroll, “We are all mad here.”

I noticed an inability to discern whether certain characteristics and performances of mine were “good,” “bad,” or “marketable,” almost as soon as I started asking myself those questions. Who exactly was I attempting to “market” myself to? The casting offices that wanted me to play their version of the perfect little Indian – a tough, brooding young man with a chip on his shoulder and, more often than not, an absentee father? Was it ever really myself, the individual, that I was even marketing, or rather a watered-down inaccurate stereotype of young Indigenous men? The only version, it seems to me, of young Indigenous men that has become acceptable in mainstream media. Was I ever really only one thing? And if I was, was I something that was beautiful?

Was I ever really only one thing? And if I was, was I something that was beautiful?

I have a deep appreciation and understanding of personal style. My aesthetic is more than just an affected, meticulously designed blend of curated clothes and hand-picked albums and films that have informed the way I present myself to the world – it is a lifestyle. So much of the grunt work of the acting industry takes place before you even step onto your first set. It requires a great deal of effort to appear aloof and nonchalant. When people speak of the acting industry as the unclimbable monolith that it is, they say “you’ll hear a lot of no’s before you hear a yes.” They’re wrong. What you hear before you get that coveted, highly sought-after “yes” is a whole lot of nothing.

The casting offices and producers you read only bother keeping an open line of communication with you if: A) you’ve booked the part, or B) they know you personally. You send in your audition and then you wait. And then they never contact you again, not even having the decency and professional courtesy to let you know whether you got the job or not.

When I first began auditioning, I would obsess over roles I didn’t book. I would research who beat me out and compare my physical features to theirs. Maybe if I looked more like them, I’d have better chances of getting cast. “Maybe if I looked more like them” quickly turned into “Maybe if I looked and was as close to perfection as humanly possible,” then I would finally be castable. I would finally be marketable. I would finally be worth having people’s attention.

This mindset spilled over into all aspects of my life, not just the acting industry. My teens were marred by an insatiable desire to be perfect. Every action was calculated. Every photo of myself ever taken, heavily scrutinized before reaching publication for public consumption. No room for spontaneity, no room for error. I would hold myself and move through the world as if there were an imaginary camera on me at all times. In a way, there was.

I’ve grown a lot since my teens and have let go of my pursuit for perfection in its most absolute form. Anyway, it never did book me any parts. But still, the tinge of annoyance I feel when required to tell casting a little bit about myself in 2 minutes or less, just so they could get a sense of who I am and what life experience I have that would make me well suited to whatever role I’m reading for this time, is still ever-present.

Attempting to be as charming as possible in under 2 minutes, mind you, is indescribably dehumanizing.

Staring into the assaulting brightness of my ring light, attempting to be as charming as possible in under 2 minutes, mind you, is indescribably dehumanizing. It feels like holding my hands out to an unseen god, on my knees in submission, begging him to love me. To choose me. And then sometimes, it happens. You finally get what you wanted so bad for so long. And then you get to set, and the assistant director doesn’t bother learning your real name and refers to you only by the name of the character you’re playing. You can tell a lot of the crew doesn’t care if you live or die, so long as you don’t die until after they’ve shot your coverage and filmed all of your scenes.

You get treated better the higher your name is on the call sheet. But the crew keeps calling you by the name of the other Indigenous actor directly below you on the call sheet, making you feel like you and he are interchangeable. But you’re there. You sit in the hair and makeup trailer and you laugh with your makeup artists. You share life stories with your hair stylist. You feel the hot lights on your face. You breathe easier knowing you are exactly where you are meant to be. You know all your lines by heart. You know everyone else’s lines. You know your cues. You know which angle to cheat on the camera, because you know which angles of your face look best. You’ve spent countless hours preparing for this moment, and nothing and no one can take it away from you.

The acting industry can be so special. It is its own form of real-life magic. But for an industry that relies on people who are human beings to be interconnected and collaborative, it is severely lacking in humanity. Every actor needs a damn good set of headshots. When I pose for mine, every click of the camera rings out like a gun being fired. Click. Click. Click. I feel as though an unseen bullet comes whistling towards me. Click. Headshot. A shot to the head. I will bleed out while smiling. Poised and posed, even in death. At least I can say that I gave them a show.

Taio Gelinas is a multi-media artist from Kanehsatà:ke. He will graduate from Dawson College with his diploma of collegial studies in Cinema & Communications in the fall of 2025. He plays rugby for the Dawson Blues, while also pursuing a career in the acting industry. In his spare time, he enjoys reading and writing.

@taiogelinas + @teenagedirtbag92

In conversation within talking circles, our works weave blankets of trust and security. The journey through these works was carefully curated with consideration of each of our intersectionalities, as well as the threading and overlapping values we share.

The spaces that art occupies, creates, or revitalizes offer conversation and empathy. The things that keep us going are shaped by rich personal and collective histories, and are enriched by community and gathering.

“Talking Circle: What Keeps Us Going,” videographed by Deb VanSlet for Montréal Serai, 2025