On November 26th, I had the privilege of meeting Sfiya, a Moroccan-born visual artist whose work transcends the boundaries of medium and meaning. This winter, she inaugurated Œil pour Œil, a captivating multidisciplinary exhibition that draws us into a world where the belief in the “evil eye,” the age-old fear of envy and misfortune, is used to examine the complex realities of migration, identity, and belonging. Through a palette of deep blues and intricate symbolism, Sfiya invites us to gaze into the emotional heart of migration, not merely as a physical displacement, but as a profound internal transformation.

Her work speaks of the tensions between the old and the new, the inherited and the adopted, the memories of a homeland that never fully fades and the uncertain search for a new home. Œil pour Œil tells the story of a journey that is as much about cultural survival as it is about personal reinvention, where the weight of ancestral beliefs like the superstitions of the 3ein, or evil eye, tugs at the fabric of one’s sense of self in unfamiliar territory.

Through her art, Sfiya explores how migration shapes the soul, how it carves out space for loss and longing, and how it complicates the search for belonging.

Through her art, Sfiya explores how migration shapes the soul, how it carves out space for loss and longing, and how it complicates the search for belonging. In her vivid expressions, the melancholic beauty of this experience emerges—an experience that, while intensely personal, also reflects a universal longing for connection, understanding and a place to call home. Œil pour Œil becomes, in the eyes of the viewer, not only a reflection on the immigrant experience but also an invitation to reflect on the shared emotions that unite us across borders: a sense of displacement, nostalgia, the ache of uprooting and the quiet hope that, somewhere, we might find a place where we can truly belong.

Before diving into my discussion with Sfiya, I want to immerse you in the atmosphere of the exhibition to offer you a fuller of grasp its message.

The light is a bright white crystal streaming through the gallery windows. As you walk up the stairs of the Fait moi l’art gallery, shades of blue reflect this light through the central window, casting an ethereal glow. Inside, the space is designed to captivate your attention—an environment where the observer feels compelled to explore every corner, like a child discovering something new. The paintings on each wall tell fragmented stories, with shifting chapters and unfamiliar characters, inviting the viewer to piece them together. This sense of wonder, reminiscent of the excitement we feel when exploring new places or traveling, sets the perfect tone for addressing the central theme of the artwork: migration.

Travelling to…

To migrate is not just to move physically; it is to journey into a new country, a new life, and into an ongoing process of questioning. Sfiya explains that this exhibition is a personal exploration of and reflection on her own dilemmas stemming from her immigration to Montréal. For her, migration is not solely about geographical displacement; it involves the transportation of emotional baggage, beliefs and knowledge. Upon arriving in a new place, an entirely different culture must be understood and, in some cases, adopted. This creates a feeling of selection: what aspects of my past should I carry with me, and what should I leave behind? How will I integrate into this new world, and how will my prior experiences shape my new environment and relationships?

How can we understand the experience of immigration itself?

Sfyia shares that these personal reflections also attempt to answer a larger question: how can we understand the experience of immigration itself? Funded by the Conseil des Arts et des Lettres du Québec, the project aims to provide key insights into the challenges and realities of migration. In a sense, it seeks to create a visual language that can be easily understood by many who share similar experiences. The dominant theme that emerges from this artistic translation is travel.

In our conversation, she expressed her belief that immigration is an ongoing journey. Coming to Montréal is not the conclusion of this process; on the contrary, the adventure truly begins here. The questions she raised about identity, belonging and integration are part of an ongoing, daily experience.

In Jérémy Mandin’s 2020 article “Aspirations and Hope Distribution,” he discusses how many Maghrebi immigrants perceive Montréal as offering a “regime of hope distribution,” where ethnicity, religion and class are viewed differently than in French society (301). While this hopeful perception may be true to an extent, the xenophobic shape of Québécois nationalism and increasingly prevalent state-sanctioned Islamophobia create challenges for immigrants of Maghrebi origin. Sfiya poignantly illustrates this constant navigation of identity in her painting El ghorba (“the escape” in North-African Arabic).

In this painting, we see a Montréal metro scene featuring a woman with an unusually elongated neck and a personified stork. In Morocco and across the Maghreb region, the stork holds significant cultural importance and is regarded as a wise and respected bird. Physically, the stork’s long beak allows it to carry objects, much like immigrants transport elements of their past, their culture and their story. This human-like stork, the imaginary companion of the woman with the long neck, symbolizes the baggage of knowledge and beliefs that we all carry.

The woman’s sad, cold expression conveys a sense of disconnect from her world, yet one might also interpret her gaze as directed at another figure—perhaps with envy, observing someone who seems to fit in more effortlessly, tinged with a touch of the “evil eye.” The depiction of the woman with her visible anomaly powerfully conveys the experience of feeling out of place, burdened by the weight of one’s past.

The woman’s sad, cold expression conveys a sense of disconnect from her world, yet one might also interpret her gaze as directed at another figure—perhaps with envy, observing someone who seems to fit in more effortlessly, tinged with a touch of the “evil eye.”

Moreover, the setting of the painting is crucial. The artist explains that she wanted to embody the theme of travel in a concrete way. The Montréal metro, much like migration, offers a clear starting point and a potential end destination, but in between, one is caught in an undefined, ambiguous space. It reflects the emotional journey of identity—an ongoing search that is difficult to understand and even harder to express. The metro symbolizes this transitory space where individuals are suspended in a continuous quest for belonging, both within themselves and within their new environments. The question remains, will we ever arrive at our destination?

Stuck in between

Looking to the other side of the room, facing the El ghorba painting, I see a vibrant canvas with blue and orange paint contrasting, each fighting to catch the light. The stork in this painting once again watches over its long-necked companion, whose head hangs over a balcony, lost in thought. In this quintessential Montréal apartment, we find two foreigners in a new home, caught in the process of adaptation.

Through this painting, Sfiya captures the dual identity that often emerges upon arrival in a new country. From the constant questioning of one’s place, a dilemma arises: two worlds, two identities, two geographical affiliations—a binary reality that proves difficult to reconcile.

This duality is reflected in the contrasting shades of orange and blue throughout Daba Tzyane and the broader exhibition. Far from being merely opposites, these colours, according to colour theory, represent a deep, conflicting tension. The interior of the apartment is bathed in blue, symbolizing the past, the inner self, while the overwhelming orange encircles everything else, representing the new and foreign reality. The woman with the elongated neck gazes out over the balcony, observing the new city she must understand and adapt to.

As Sfiya explains, this sense of duality often feels like a curse. “When we leave a place, will we ever truly arrive at our destination?” she asks. This sense of displacement is permanent, and for many immigrants, even after years in a new country, the process of rooting oneself in a new land can feel endlessly elusive. Many, like the elongated woman in the painting, constantly question how they will fit in, whether they truly ever will.

This duality transcends the individual; it becomes generational. During our conversation, we laughed about how many people, young and old, whether immigrants or second-generation, often express a desire to return. My sister, born and raised in Montréal, after visiting Algeria only once now dreams of going back to buy our ancestral land.

Will we ever find balance? I believe the issue lies in the binary thinking we often impose on our identities. We want to cling to a singular, unified self, one that is consistent and coherent. But this yes/no, black/white, blue/orange way of thinking is limiting and creates inherent conflict. Close your eyes and look again at the painting. Do you see how the orange gently merges with the blue in the apartment? Isn’t it beautiful? Notice how the two colours complement each other, creating vibrant narratives of necessary contradiction.

It is this very complexity that gives rise to beauty, just as the painting’s vibrant contradictions create something uniquely powerful.

As Nadir, an interviewee in Mandin’s article, reflects: “The day I arrived in Montreal, I understood that I was not simply Arab. I was an individual who was, among other things, Arab—but who also possessed a multitude of other identities” (306).

This duality is not something to resolve but to embrace. It is this very complexity that gives rise to beauty, just as the painting’s vibrant contradictions create something uniquely powerful. While it may be challenging to navigate both identities every day, it is this very tension that brings depth and richness to the immigrant experience, and to the artwork itself.

Œil pour Œil

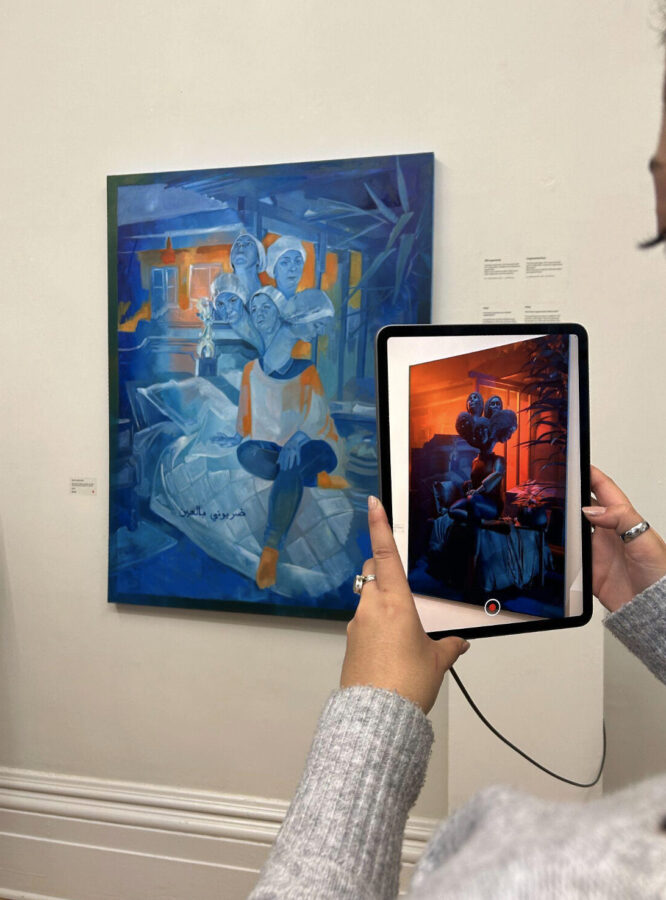

I walk past the door adorned with beads and cardboard assemblages, and I notice something strange: a creature, an elongated-necked woman—five of them, to be exact. This creature has a name: Aisha. She is Sfiya’s aunt, and is portrayed in a distorted form, her long neck and multiple heads looking in different directions. In the left corner, written in Arabic: ضر بوني بالعين (“On m’a porté l’Œil”—“I was hit by the evil eye”). Sfiya often tells me how important her aunt’s stories were to her growing up, stories about misfortunes and curses caused by the 3ein—the evil eye.

As Sfiya explained, Aisha taught her about this belief, which she carried with her through migration. But what is the 3ein, or nazar, or máti? Many cultures around the world share some form of the evil eye belief—where one can be cursed by envy or ill intentions, often through a compliment, a look or an unspoken judgment. This belief is expansive and can be applied to a range of events and experiences with varying degrees of intensity.

For Sfiya, the beauty of 3ein lies in its multifaceted existence. It exists on different levels: the familiar pop-culture symbol of the large, dark blue eye or ornate jewelry; the mashallah spoken after a compliment to ward off envy; and, most significantly, as a way of connecting with others who share the same cultural knowledge. This belief becomes a kind of private, shared culture that creates bonds and a sense of community, especially within diaspora spaces.

However, the 3ein belief also has its darker side, one that can become obsessive and all-consuming. In Sfiya’s painting, Aisha is distorted into a tormented figure with multiple heads, symbolizing the overthinking and anxiety that come with an excessive focus on the evil eye. The painting evokes a constant fear: that any misfortune or setback must be the result of someone’s envy or bad intentions. This is where the belief in 3ein becomes both protective and potentially damaging.

For the migrant, this “lost object” is often their cultural identity, which can feel threatened in an unfamiliar and sometimes hostile environment.

In the context of migration, the 3ein serves as a means of coping with the uncertainty and hardship that often accompanies displacement. As Sarah Ahmed notes in The Promise of Happiness, “suffering becomes a way of holding on to a lost object” (142). For the migrant, this “lost object” is often their cultural identity, which can feel threatened in an unfamiliar and sometimes hostile environment. The experience of racism, for example, becomes a way to explain failure or alienation. Similarly, for migrants who face prejudice or exclusion, 3ein offers an explanation for their suffering; it becomes a way to process painful experiences and maintain an attachment to their cultural roots.

However, the danger of such beliefs, as Sfiya’s painting suggests, is when they are taken to an extreme. Aisha’s fear of the 3ein manifests in her avoidance of compliments, worried that she might unintentionally curse someone with envy. This reflects an unhealthy obsession with the belief, which limits her ability to engage freely with others. The question Sfiya raises through her art is: How do we reclaim or reappropriate these beliefs?

The 3ein is not just a protective force; it is a means of holding onto something lost in the journey of migration, a way of understanding and navigating the world that connects the individual to a larger community. But when taken to extremes, as in Aisha’s case, it can lead to isolation and anxiety. As migrants, the challenge lies in finding a balance between maintaining cultural beliefs that offer comfort and connection, while avoiding their potential to become obsessive or harmful.

Giving back to the child

I finish exploring the exhibition and return to the front, waiting for the guided tour to begin. As I stand before a familiar scene, a painting of an afternoon tea, I feel a wave of nostalgia. I laugh with my friend, noting how the older women with long necks seem to murmur to each other, while the atay (tea) sits on the table and the children play together in the background. The vibrant contrast of blues and oranges in the composition creates a lively, almost tangible sense of warmth and belonging.

This scene, a memory of shared experience, highlights the fluid nature of the 3ein belief within the fabric of culture. We’ve discussed its deviations and transformations, but the question remains: why do some people remain so attached to it? This is precisely what the painting 3rada conveys.

The image of women gathering for tea, laughing, gossiping and telling stories, is not just a personal memory for me, but also for Sfiya and countless other Maghrebis. It’s a representation of the maternal oral tradition, where we learned about our family’s history, culture and, inevitably, the 3ein. This tradition was passed down through stories, through al hikma (morals) that shaped our understanding of the world.

In our conversation, Sfiya shared how, while in Morocco, family photo albums held little sentimental value. But when she returned after her migration to Montréal, these images became treasures. The scenes, once overlooked, suddenly held immense significance.

The things we once took for granted, like the simple act of gathering with family, sipping tea or listening to stories, take on a new, deeper meaning when we are far from home.

The act of migration creates a melancholia for the past. The things we once took for granted, like the simple act of gathering with family, sipping tea or listening to stories, take on a new, deeper meaning when we are far from home.

In this way, migration confronts us with a kind of emotional contradiction: the desire to move forward and embrace the present, but also a deep longing to stay anchored in the past. This melancholia, this emotional weight of memory, makes it hard to fully immerse in a new life. As Sfiya’s reflection shows, childhood memories, whether they are cultural traditions like the stories of the 3ein, or the simple scenes of home, serve as anchors. They are both a source of comfort and a barrier, a link to a past that feels increasingly distant and unreachable, yet remains deeply cherished.

Sfiya cherishes her memories and her Aunt as a living embodiment of this oral tradition and culture; she also recognizes how her Aunt, in turn, holds onto the belief of the 3ein as a way of preserving the family’s history. For both of them, the 3ein becomes more than just a superstition; it is a thread that connects them to a cultural heritage that is, in many ways, embodied in their family stories and rituals. Through these beliefs, they both find a way to keep their roots alive in a world that often feels like it’s drifting further away.

A contradictory future, but beautiful

In Western thought, the act of clinging to the past is often seen as unhealthy, a hindrance to personal growth. The notion of “moving on at all costs” tends to dismiss attachments to past experiences as burdensome or counterproductive (Ahmed, 138). What makes this exhibition so impactful is its recognition that holding onto the past and experiencing melancholia are, in fact, vital for migrants. The emotional weight of memory and nostalgia is not something to be discarded, but rather embraced as an essential part of the migration journey.

Through Œil pour Œil, Sfiya’s personal exploration of migration becomes a window into a shared human experience. While each migrant’s story is unique, they are united by a common thread of étrangeté, a feeling of alienation and displacement that transcends individual circumstances. This sense of duality, the push and pull between the desire to protect one’s cultural heritage and the need to build new connections, shapes the emotional landscape of migration.

The exhibition uses 3ein as a symbol of this delicate balance, showing how beliefs, rituals and memories act as a bridge between the past and the present. The 3ein is not just a belief, but a way of holding onto a piece of home, a form of protection in an unfamiliar world. In doing so, the exhibition invites us to reflect on the importance of community and the role of cultural heritage in navigating the complexities of living between two worlds. It offers a space for dialogue, where these contradictions—nostalgia and progress, isolation and connection—can coexist, heal and allow for understanding.

Sfyia was already preparing for a second exhibition, scheduled for the beginning of the season. This exhibition promises to explore migratory emotions in a fresh and innovative way, offering a deeper, more nuanced perspective. Mark your calendars: the exhibition is on until September 26, 2025, at the Galerie Atelier RAM.