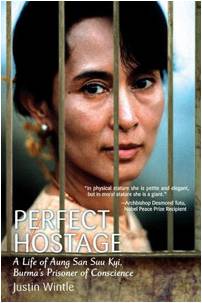

PERFECT HOSTAGE. Aun San Suu Kyi, Burma and the Generals. By Justin Wintle. Arrow, 2007.

In Burma there is no prejudice against girl babies. In fact, there is a general belief that daughters are more dutiful and loving than sons and many Burmese parents welcome the birth of a daughter as an assurance that they will have somebody to take care of them in their old age. Aung San Suu Kyi, Letters from Burma, 1997.

PERFECT HOSTAGE is an imperfect biography of Suu Kyi in the sense that the author devotes almost half of the book to the life and times of Bogyoke (General) Aung San, Suu Kyi’s father as well as the father of modern Burma, and the generals that have controlled the country ever since. Yet the author could not have done otherwise. In order to understand what has made Suu Kyi the modern-day symbol of peaceful resistance, it is necessary to be acquainted with Burmese history and the events that catapulted her from an ordinary life as the wife of an academic to the extraordinary position of Prime Minister Elect (but never in office) of her besieged country.

PERFECT HOSTAGE is an imperfect biography of Suu Kyi in the sense that the author devotes almost half of the book to the life and times of Bogyoke (General) Aung San, Suu Kyi’s father as well as the father of modern Burma, and the generals that have controlled the country ever since. Yet the author could not have done otherwise. In order to understand what has made Suu Kyi the modern-day symbol of peaceful resistance, it is necessary to be acquainted with Burmese history and the events that catapulted her from an ordinary life as the wife of an academic to the extraordinary position of Prime Minister Elect (but never in office) of her besieged country.

The general public is very much aware of the fact that she has been under house arrest for more than fourteen out of the 20 last years. It also knows that she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991, as well as a panoply of prizes from other countries, including the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought and the Jawaharlal Nehru Prize for International Understanding. This same public also knows that her political achievements came at great personal cost: prolonged separation from her children and husband and her husband’s loss to cancer without having had a chance to visit him at his deathbed. In fact, she has been criticized for not being a wife and mother before being a political creature. What is not so well known is the exact nature of her achievements and that again, is understandable, for they are intangible, although no less worthy of admiration for that.

Aung San, Suu Kyi’s father, was assassinated on the eve of Burmese independence when she was barely two years old. He was instrumental in bringing about Burma’s independence from the British and is credited with creating the modern day army which still controls the country. Suu Kyi, like any Burmese citizen, was brought up to revere him and seeing her father’s picture in public spaces and on bank notes must have reinforced her sense of destiny as her father’s political heir. However, as she grew up she realized that the army had strayed from its original role of protector of the people.

From an early age she knew she was called to serve her country but was not clear as to the exact role she would play. After having obtained a degree in political science and economics she worked for the United Nations in an administrative capacity and then married Dr. Michael Aris, a British citizen specializing in Tibetan culture. They lived in Bhutan for several years and then settled down in England with their two sons. There she obtained a doctorate in Oriental Studies. When her mother had a massive stroke in 1988 Suu Kyi returned to Burma to nurse her and the rest is history, as the saying goes.

The last twenty-odd years have been marked by civil unrest in Burma, brutal repression by a succession of generals and a general awakening of the population to democratic alternatives. Throughout all this Suu Kyi has stood her ground, been arrested and tortured and remained under house arrest on and off. During this period, Suu Kyi has continued rallying the people around her either openly in her house or in front of the family compound through clandestine messages. She even managed to win the first –and only general elections- held in Burma but was never allowed to take up office.

The international community, through the United Nations and diplomatic negotiations, has continued to support her peaceful movement. It has awarded her accolades in the form of honorary degrees and prizes which she has funneled back into her humanitarian work. However, author Justin Winkle’s appreciation of her role is not so simplistic. While admiring her courage, determination and integrity, he believes that armed struggle is sometimes necessary to topple violent regimes and that passive resistance has actually played into the hands of the regime. In fact, his contention is that her intransigence has resulted in the death of many of her supporters and bolstered the dictatorship that has in her “the perfect hostage” who serves as a bargaining chip with the outside world.

The Nobel Prize Committee citation prefers to look at the broader picture:

“…In awarding the Nobel peace prize for 1991 to Aung San Suu Kyi, the Norwegian Nobel Committee wishes to honour this woman for her unflagging efforts and to show its support for the many people throughout the world who are striving to attain democracy, human rights and ethnic conciliation by peaceful means”.