In retrospect

Were they to look back afresh, my family would perhaps recognize the telltale signs of his impending death. To them, however, his death was sudden and premature, a tragic casualty without any forewarnings. “We were at a point in time when our lifelong efforts were just about to pay off,” my grieving mother ruefully remonstrated against our fate. Unlike her, I barely knew him as an adult. I left home at the age of nine in pursuit of a future that was inaccessible in our province. Away from my family, amidst strangers and in moments of solitude, I often consoled myself with the thought that after I had found my calling, I would return to live with my family. More than two decades went by with no immediate return in sight. A week after I commenced my graduate studies in the Midwest, my father drew his last breath.

Whereas my mother and siblings grieved the loss of someone with whom they had spent much of their lives, I regretted the impossibility of finding an opportunity to do so.

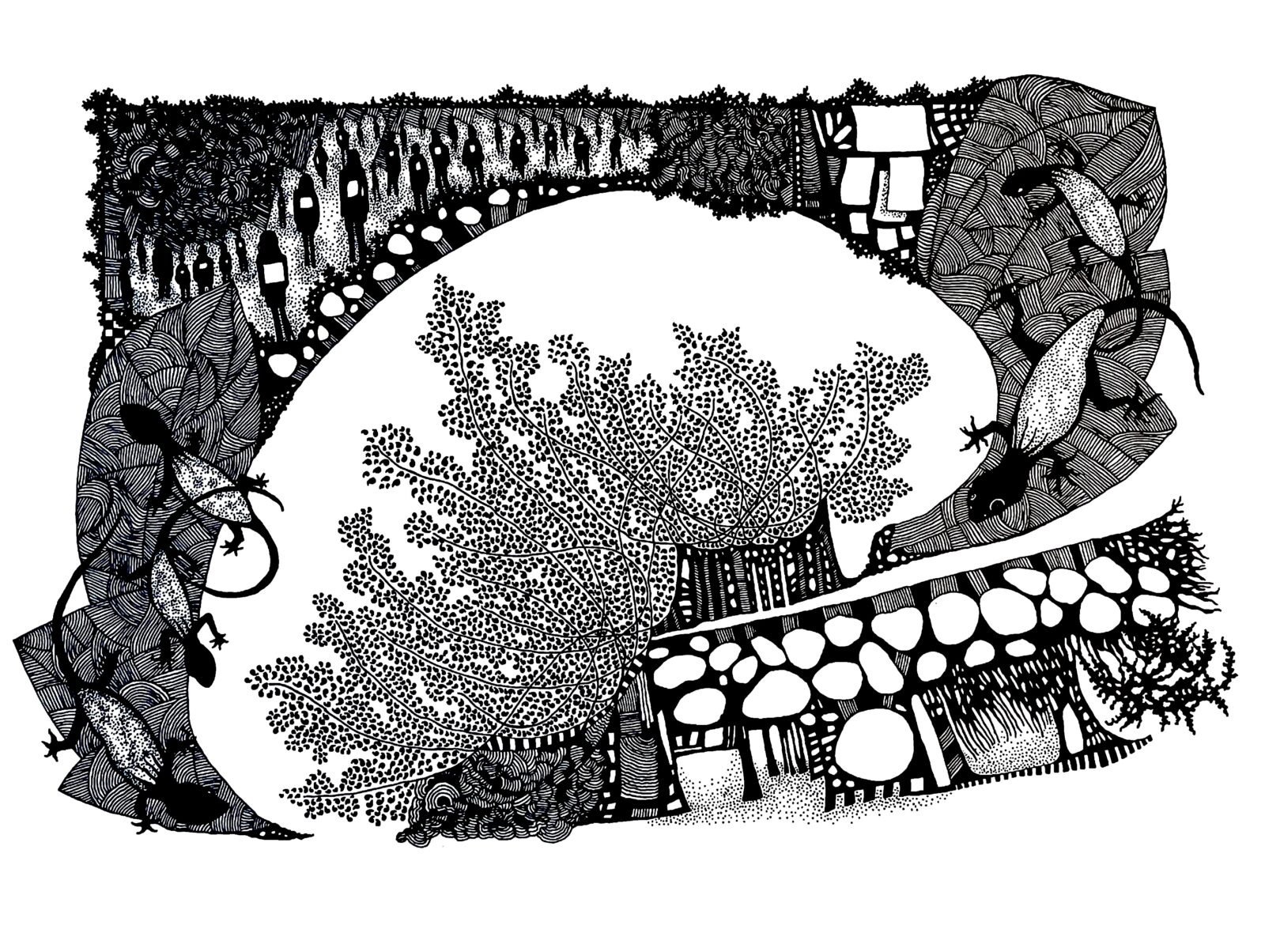

Grief unfolds in unusual ways: it rarifies our memory and mutates our perception of time. Whereas my mother and siblings grieved the loss of someone with whom they had spent much of their lives, I regretted the impossibility of finding an opportunity to do so. A plethora of emotions and memories inundated my mind, and I did not quite know how to grapple with their currents. As I gazed outside my window, a crowd of mourners gathered in our garden. The Madhumalati shrub had grown all over the window sill. Several house lizards had surrounded me. Their clicking sounds reminded me of the long hiatus in my artistic practice.

Returning to art

In my younger years, I engaged in artistic practice because of the thrill I experienced in creating images that were attractive, meaningful and pleasing to my mind. Whenever I was low in spirits, I would revive myself through artistic practice. What existed between my mind and my vibrant art supplies was an unmitigated desire to create an object of beauty that would inspire awe and wonder in the viewer. During the hours I immersed myself in artwork, I would lose all sense of external time, my past experiences and the outside world. Artwork shielded me from the vagaries of my immediate present.

I had spent so few years there with my father that I wanted to hold on to every moment.

After my father’s death, I could not let go of the time I had spent at home, nor could I let artwork alienate me from the provincial realities of our lives. I had spent so few years there with my father that I wanted to hold on to every moment. These intermittent experiences were, after all, the sole means by which I could begin to fathom who my father was, how he changed over time, and why he met an untimely death. This desire to cling to the memories of a lost time and to unravel the everyday experience of a provincial life transformed my artistic practice.

Provincial portraits

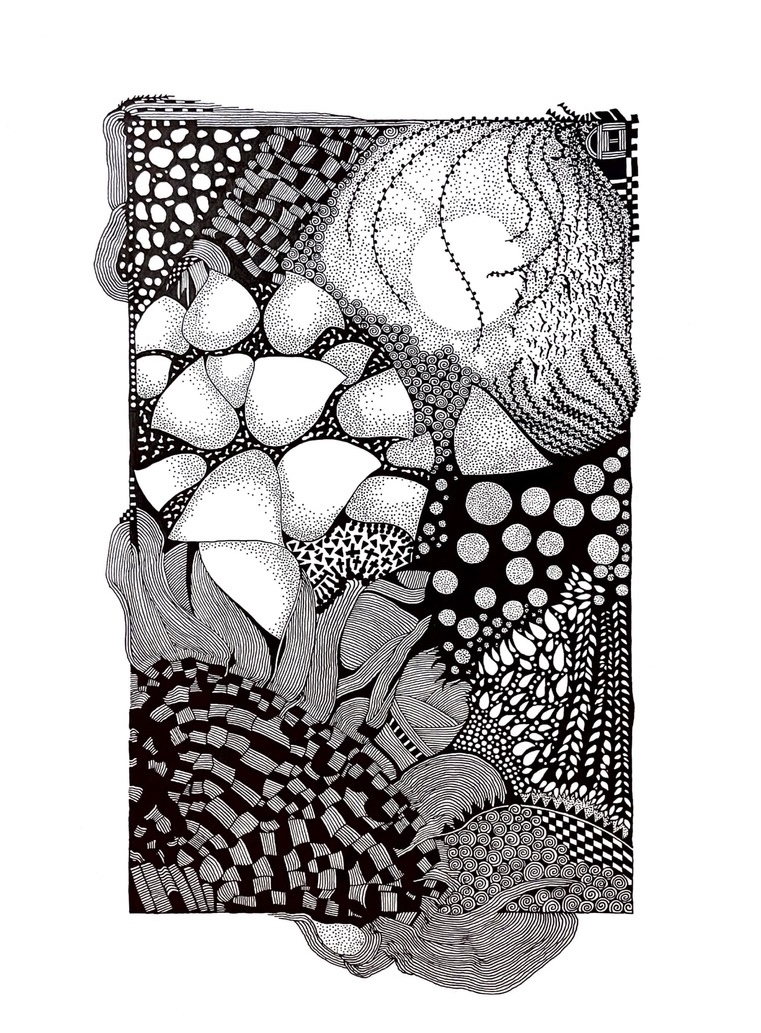

The colourful paintings of my yesteryears seemed inappropriate—somewhat vulgar and rude—to convey the sombre reality of our life. As a child, I was initiated into the Madhubani style of painting that Maithili-speaking communities practice on festive occasions. Maithili is a language spoken in some of the southern and eastern provinces of Nepal and in the eastern states of India, particularly Bihar and Jharkhand. When the final vowel -i of the noun Maithili is elided, it forms the substantive Maithil. A vast majority of Maithil speakers are Hindus, whose cultural imagination is intimately attached to their part-mythic, part-historical homeland Mithila. Madhubani painting is alternatively known as Mithila art. Traditional Madhubani artists rarely used the techniques of washing, shading, layering and overlapping colours for depth perception. Although I espoused their technique and style, I could not embrace their vivid, cheery colours.

How tragic would a creative work be if it failed to unravel the complex realities of ordinary folks?

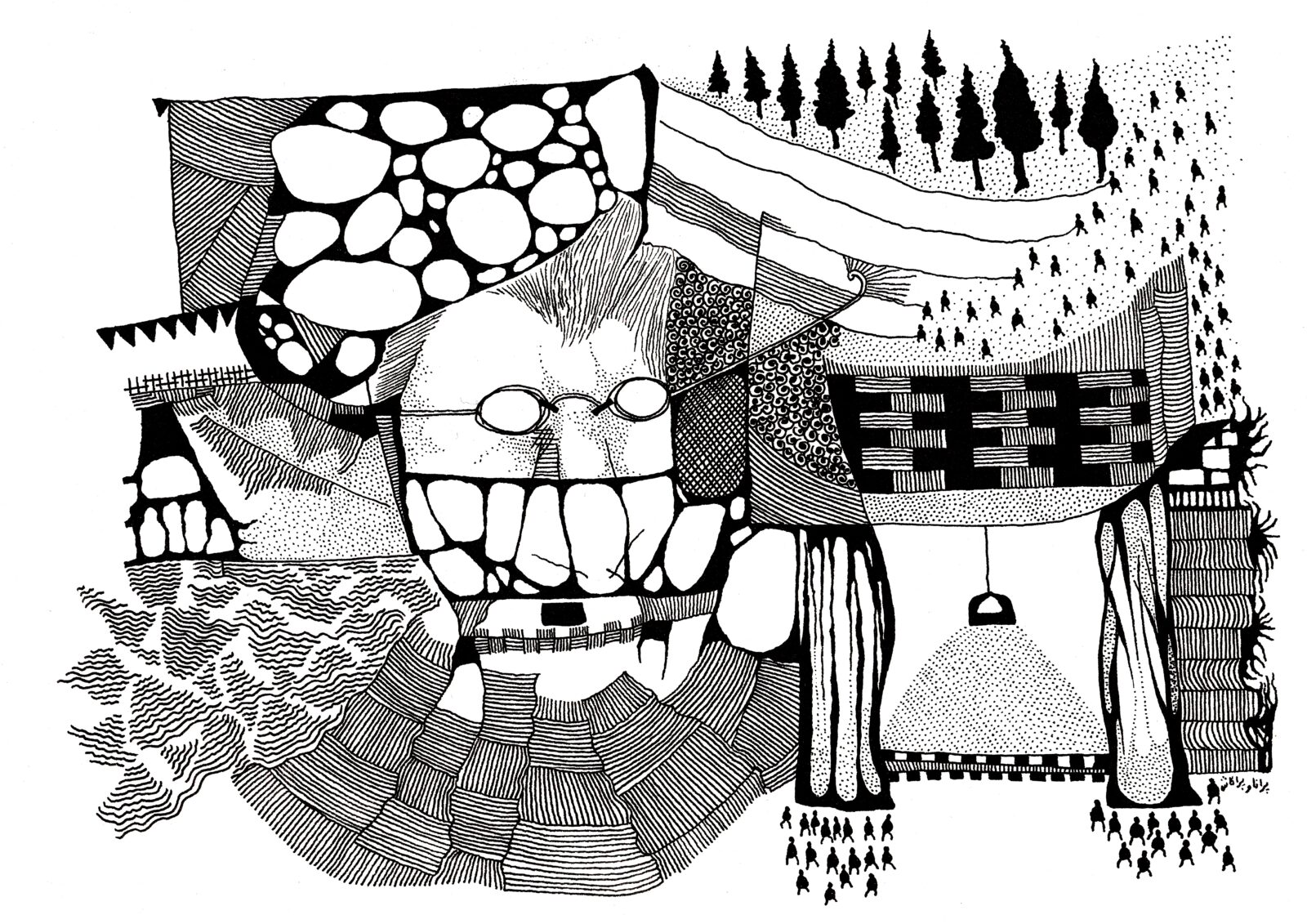

The use of monotones was not without challenges either. Monotones evoke a sense of boredom and lifelessness. Since provincial communities are—more often than not—stereotyped as mundane and ordinary, monotones bear the risk of reifying preexisting biases and prejudices against them. How tragic would a creative work be if it failed to unravel the complex realities of ordinary folks, who—to borrow V. S. Naipaul’s words in A House for Mr. Biswas—seem “to have lived and died as one had been born, unnecessary and unaccommodated”? When I mulled over the creative potential of different colours for portraying provincial backwaters, it dawned on me that the binary of black and white was, in effect, a powerful trope for probing who we were and what we aspired to be.

Narrating life

Maithil women like to tell stories and folktales as a pastime. After she had finished cooking meals for us, especially on long summer evenings, my mother would narrate stories to me and my siblings. Her tales related as much to mythologies and epics as to her experiences of growing up in a remote, hostile village in the floodplains of the River Koshi. The anecdotal ones gave us much courage and strength. “You can run away from a dangerous place, but you can’t run away from your timid mind,” she would often tell us.

We lived in a town that was notorious for crime and violence. Our neighbourhood was always abuzz with stories of criminal masterminds and daredevil thugs. When I was barely 12 years old, my father received a death threat from an infamous criminal, who acted on behalf of the dominant caste groups in our province. In the preceding months, that criminal had killed a couple of professors on the university campus in broad daylight. He demanded that my father stop teaching at the university and pay a protection fee to live in our town. My father’s death was nearly at our doorstep.

My father rarely narrated the story of his struggles. My mother was always his relater, and she was a skilled storyteller. When his friends came to inquire after our wellbeing, she would move them with stories of her family’s valiant resistance. But the night before he passed away, my father strangely lapsed into a fit of storytelling. My mother was his sole audience. He recounted stories of growing up in an impoverished family, of fleeing from a rural community that was reluctant to support his education, of aspiring to study in reputed colleges, of bringing up a family in an up-and-coming town and of hoping against hope to salvage whatever remained of his ancestral heritage.

Remembering home

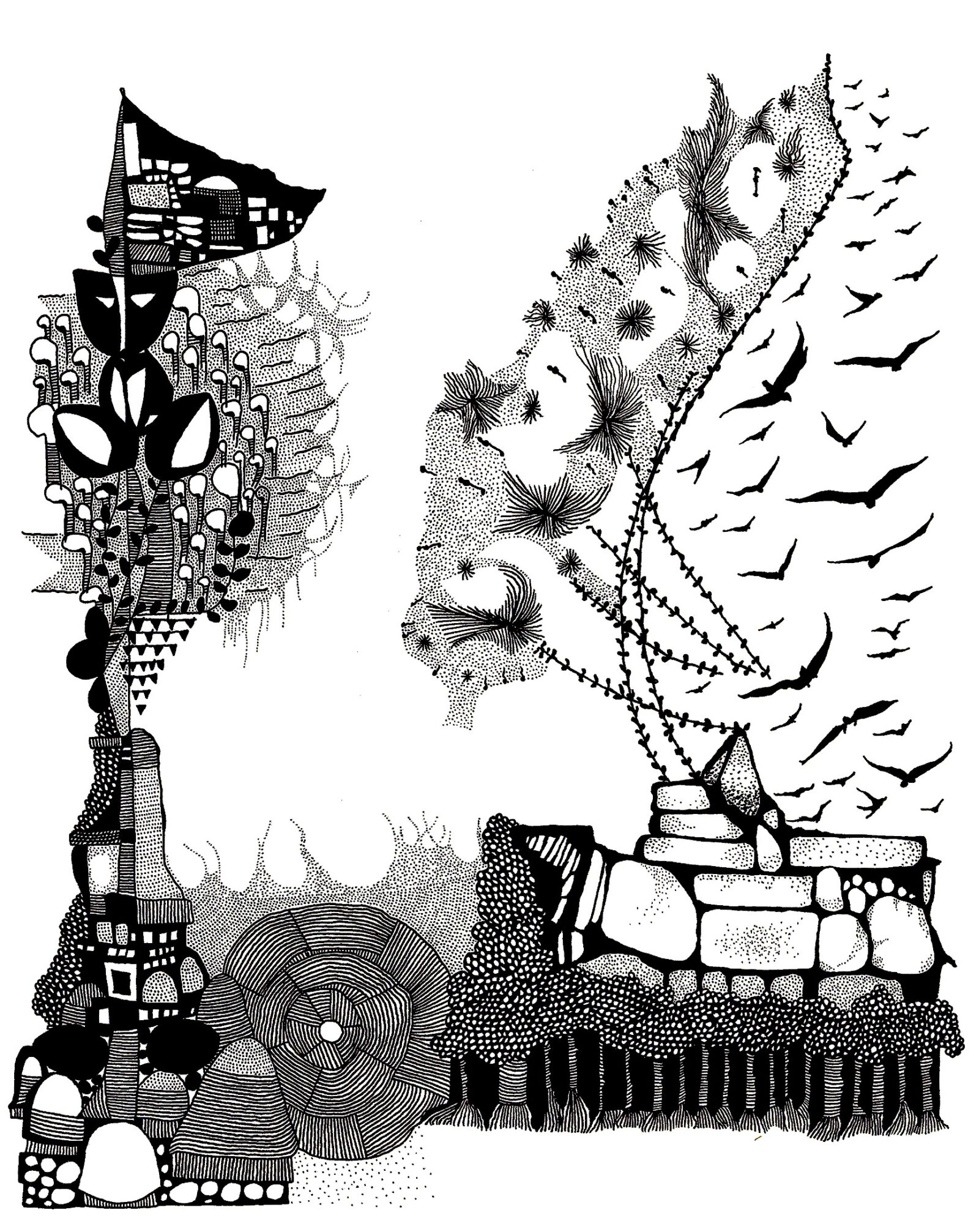

After two rounds of strenuous examinations, I was chosen to study in a residential monastic school. My parents were relieved that I had found a safe haven to continue my education. My school was located in the neighbouring state, in a tribal region called Santhal Pargana. Monastic life was routine-bound and harsh. I would often miss my home and storytelling sessions. Our summers were long and dry. Food and water were scarce. Birds of prey scampered for a morsel of meat. Their cacophony was ominous and sinister. The presence of tribal huts, haystacks, weaverbird nests, forests, boulders, flags and confetti evoked nostalgia and longing for home.

Back home, social and political conditions continued to deteriorate. One of my aunts, who lived close to a forested area, died in unusual circumstances. When her siblings visited the site of her death, they could not tell whether their sister had been murdered or had died of natural causes. Her neighbours gathered to watch the spectacle of a dead body. But no one revealed anything about her death or killing. Fear silences people. Silence kills people.

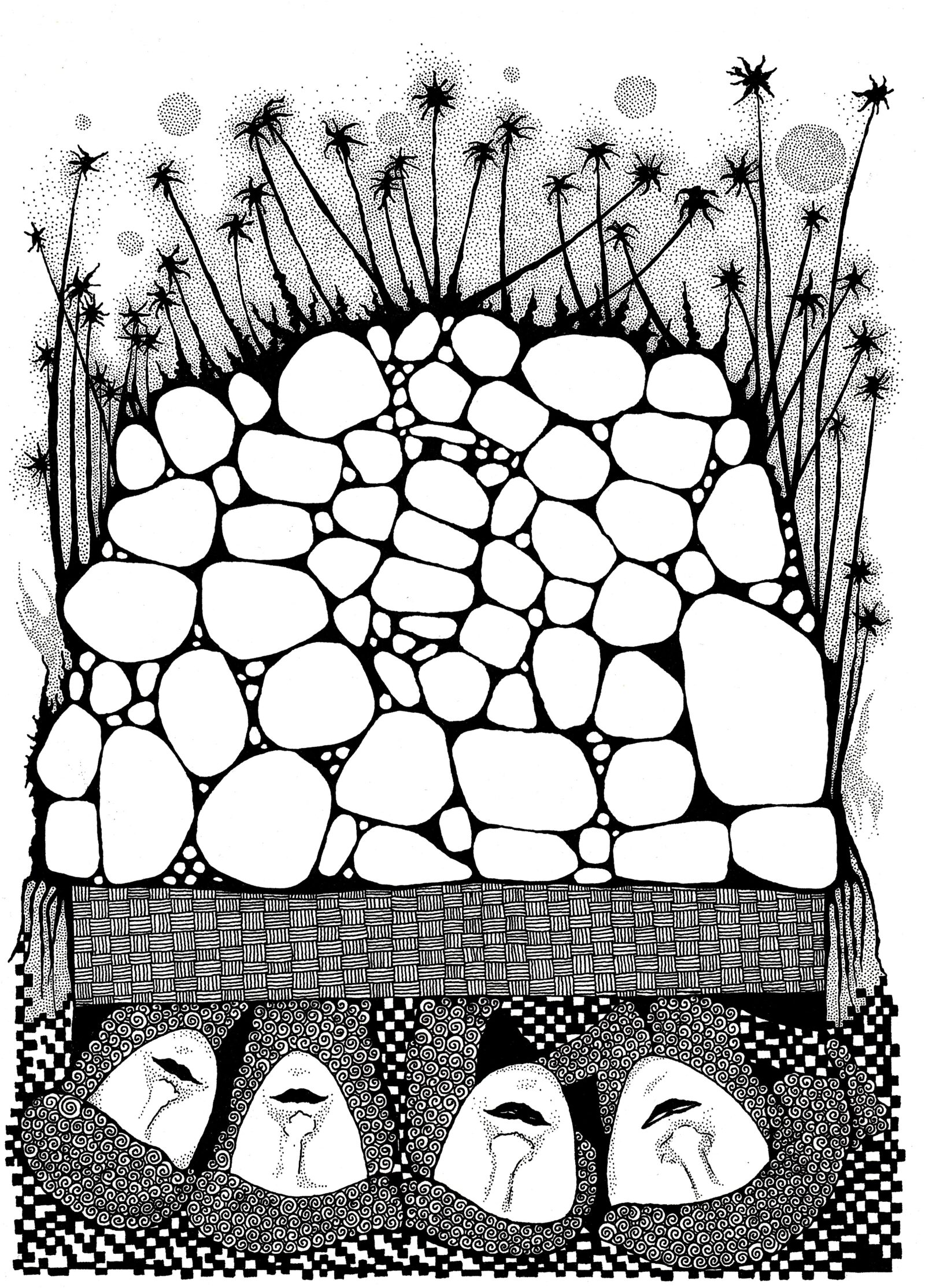

There has since been a massive spike in the spate of extrajudicial killings and lynchings. Murder and death were rampant in my hometown when I was still a child. I was seven years old when I saw a murdered body for the first time. Supremacist caste groups would kill underprivileged Muslims, tribal peoples, lower-caste Hindus and other minorities with impunity, sometimes simply by pelting them with bricks and lathis. Buried under a heap of stones and boulders, dead bodies cannot tell their stories.

A quest for hope

Despite the hardships they faced in their lives, my parents remained in their province for a variety of reasons. The local college where my father taught had an illustrious history. The university town was home to several leading intellectuals, who led grassroots socialist movements against the authoritarian policies of the central government. Its railway station was well connected with metropolitan cities. My father could collaborate with academic communities in Kolkata, Patna, Kanpur and Varanasi. When my parents arrived in town, they owned no property of their own. As they set about building their lives from scratch, they could not—given their abject poverty—think of searching for a new job in a different place. The social and political conditions of the town had not yet deteriorated, and their emotional attachment to their provincial cultural heritage was still unwavering.

The year my father died was arguably the worst year for Indian democracy since its independence from the colonial British rule.

Although my parents were Hindus, they built their home in a Muslim-majority area. Our Muslim neighbours cared for us immensely. They offered my parents all the help, support and guidance that was needed to thrive in that place. When the caste politics worsened in the town, my family felt safer in the company of our Muslim neighbours. They were trustworthy and compassionate. The year my father died was arguably the worst year for Indian democracy since its independence from the colonial British rule. Hindu supremacist groups consolidated their power like never before. The violence against minorities was quite pervasive in independent India. It was to get much worse under the new government.

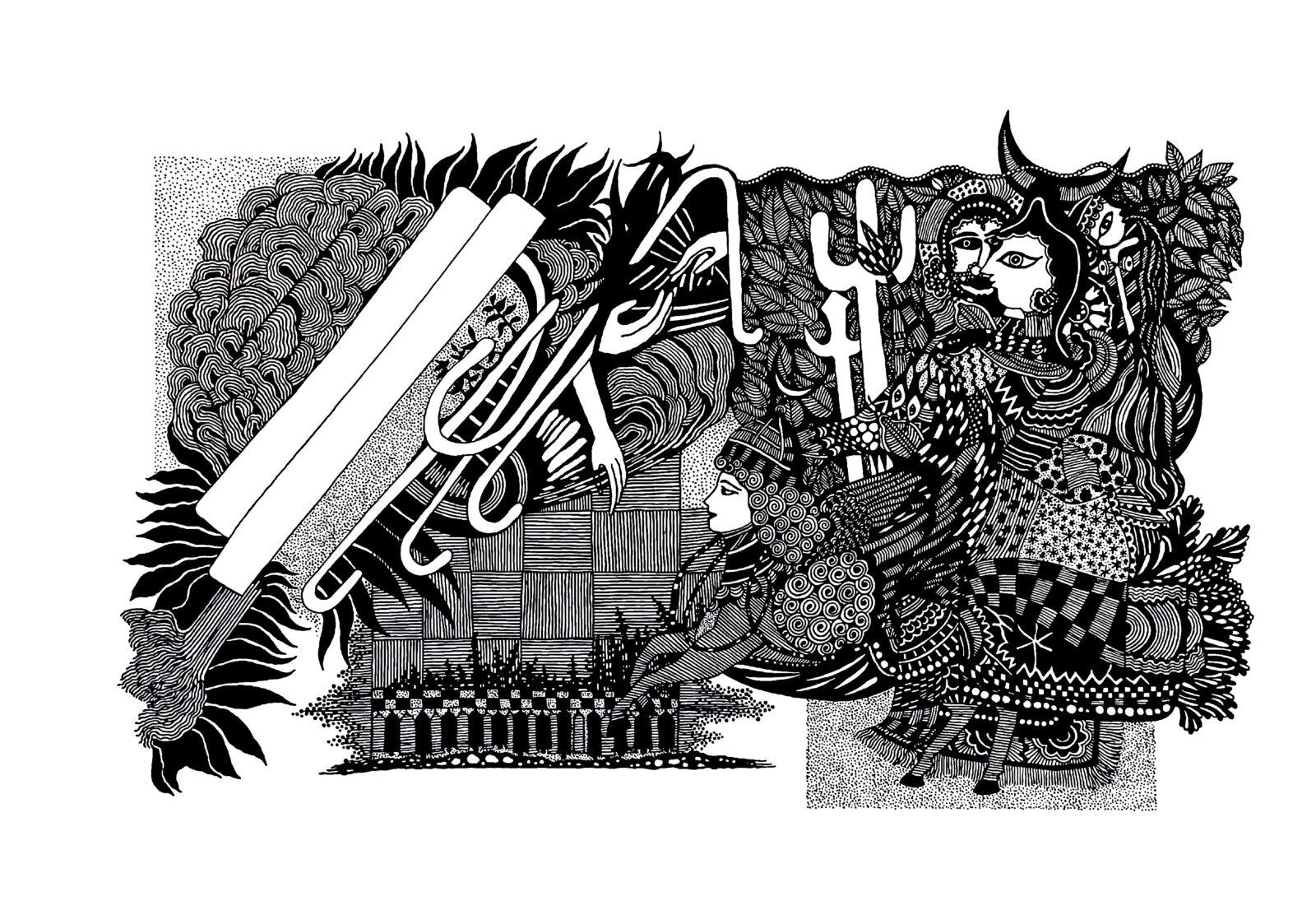

As I mourned my father’s death, I wondered how my family would cope with this tragedy in a politically fraught nation. Would they remain as deeply attached to their provincial cultural heritage and Muslim neighbours as they had been in the past? Two images filled my agnostic mind. One was of the mythological creature Buraq, who carried Prophet Muhammad to heaven. As related by tradition, it was during this ascension that Prophet Muhammad’s body was purified and filled with wisdom and belief. The second image was of my widowed mother singing a Maithili song about the night Goddess Parvati took Lord Shiva as her consort. Parvati’s parents disapproved of her marriage to the uncouth addict Shiva. But she prevailed upon them to let her marry him, and Shiva eventually brought much joy, fortune and solace into their lives.

In light of these incongruous images, I wondered whether contemporary religious communities would notice traces of their common humanity, their mutually resonant quest for selfless love and harmonious coexistence. Would a Buraq bring a lovelorn Parvati to Shiva? Would a Shiva seek Buraq’s guidance in chaperoning Parvati to their abode on Mount Kailash?