I like to think my mom and I are quite similar. Both middle children, we embody the trope to the max: non-confrontational, generally agreeable, carrying the weight of the world on our shoulders while wanting to be sources of stability in the household. We were reticent kids, painfully self-aware, teeming with anxiety.

There was a struggle to feel a part of the group: this inability to fully connect, as if we were missing some key component that would grant acceptance and enable us to join the fold. Maybe this is why we were both drawn to reading. It wasn’t an escape, necessarily, but it allowed participation; inhabiting a space fully and safely, free from the awkwardness and alienation of real life. Each good story offered some semblance of belonging.

Where we diverge in this regard is shaped by the worlds we grew up in. Growing up in 21st-century Houston, I saw other brown faces: we weren’t the only ones who had laid down roots. When my mom grew up here, there were no familiar faces. As she puts it:

What we call a diaspora now was merely a scattering of colour then.

Lubna Nazarani

Moreover, I had wider access to narratives that aligned with the life and identity I was given. By age 12, I was well acquainted with authors like Arundhati Roy and Jhumpa Lahiri. My mother’s literary landscape was steeped in white.

If you read the women, that was something, or if you read the Russians, that was something, but otherwise, they were all white men.

From a young age, then, I had anchors of familiarity: words and worlds that gave me a language for myself. For my mom, there was no such language. Her struggles were relegated to the backseat of inconsequence.

Who are you going to say that to, and who’s going to hear you?

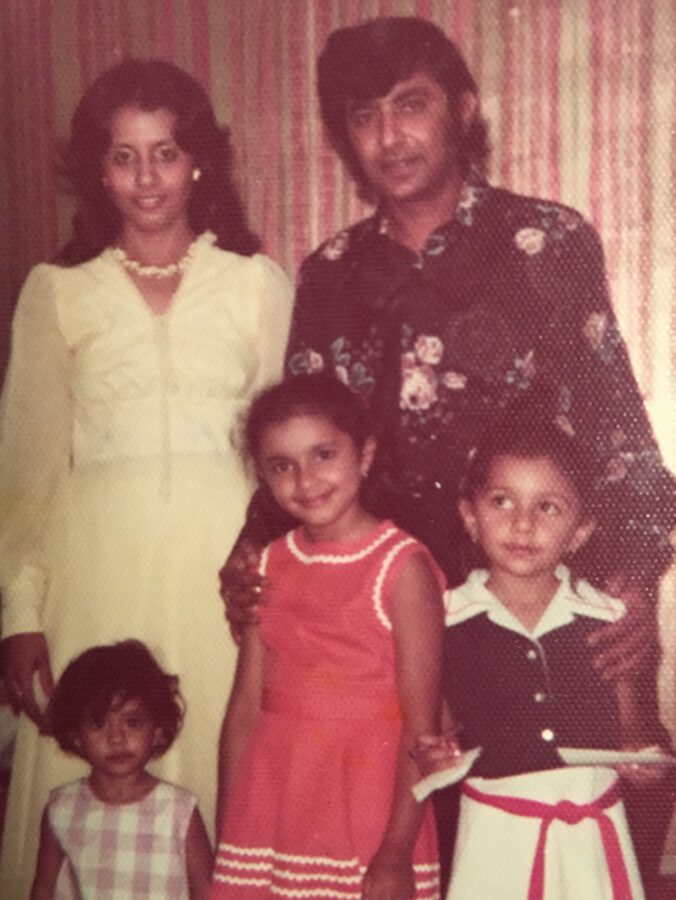

My mother arrived in Houston when she was 18 months old, brought by my Nana and Nani alongside her older sister, my Dolly Khala. Their younger sister, Nadia, had just been born and was left with relatives in Karachi, with the unfulfilled promise that they would return for her shortly. My Nani was barely 22, my Nana a few years older. Their first apartment had one bedroom with a mattress on the floor. Their first car had a missing door on the driver’s side. They had roughly 30 dollars.

That first night, my Nana started working. Able to secure a job as busboy at a steakhouse, he spent those early days in alien land lighting his boss’s cigarettes. My Nani, overwhelmed and scared with two children, would stay in the apartment with the doors locked. As she recalled, “For a while, it was just so new. It was a different world.”

For my Nana, surviving the unfamiliar wasn’t new. The youngest of 10 siblings, he had dropped out of school at an early age, finishing his education on the streets of India and Pakistan. At 16, unable to endure the callousness of his stepmother, he ran away to London. Miraculously finding a job at a bakery, he stayed for six months. In Houston, after cycling through various jobs, he began buying used and broken cars, repairing and selling them at auctions. It was this sense of jugaar that defined his approach to life, fueling resilience in the face of the hardships Allah dealt him.

He was street smart. It’s when I think about these little things that I realize: he had guts.

A Gujrati Kathiywadi, my Nana hailed from a very conservative background and carried the belief that everyone here is lazing around in their underwear and waiting to have sex. His unwillingness to adopt the customs around him, coupled with his absence from his homeland as its customs evolved, left him stuck in what he brought with him in the 70s. He was the melancholic migrant: rooted in the past, fearful of reorienting himself to the ideals of a new nation. “I’m not going to be American. We’re not American,” he would declare.

Rather than equip his daughters with tools to navigate the west, my Nana sought to shield them from it. This was manifest in strict rules and clearly delineated gender roles. My mother couldn’t engage in anything resembling nakhre (drama).

Having daughters is always a scary thing for a father, especially an eastern father. The idea of keeping your family safe was very much “without, not within.” “No, you can’t go out. No, you can’t talk to this person. No, you can’t do this. No, you can’t do that. No, you can’t go here. No, you can’t go there.”

Her response to this upbringing was to not react. She navigated much of her adolescence in silence, not ruffling feathers, not rocking the boat. The tendency to remain compliant seemed to overpower any urge to exert autonomy. Her passivity allowed her to go through life without much conflict, but it also bred complacency: a double-edged sword. This is not to say that her upbringing was devoid of longing. If anything, it was shaped by it.

You struggle for meaning because you don’t know where it needs to come from. I did have this longing for something more certain than what I felt, than what I had in hand.

Growing up without relatives, without other people who looked like her, compounded by the floater-like tendencies of a middle child, made for a marginalizing experience. My mother’s sense of not belonging wasn’t something she had stumbled into. It was something innate, intrinsic to her core.

It was a statement of fact. I am not a part of this, I can’t be a part of this. None of these things that anybody is talking about or planning or thinking about or wanting to do—none of those things will apply to me.

In sixth grade, she was badly bullied by a group of white girls solely for being brown. They spoke about her in the third person as though my mother were invisible, even while she stood right there. She was made to step outside herself. To stare at a fragmented reflection of her own personhood imposed by the white gaze. A Black boy in her class would also pick on her, tossing remarks that would elicit laughter from the teacher, leaving my mother feeling dissociated. In instances like these, whiteness wasn’t simply the property of white bodies but a structuring force that could be performed and upheld by anyone within its framework, even those it sought to marginalize. In instances like these, my mother’s humanity was flattened, reduced to caricature: a shrinking inside.

At 18, my mom returned to Pakistan for the first time. Laden with countless American products for her relatives, she went to stay with her sister, Nadia. It was a moment of connection between the two of them. They ventured into the streets together, taking rickshaws to shop and look at fabrics and textiles. It was striking to be surrounded by people who looked like her. Still, she carried a persistent sense of not fully belonging there either.

Some of this disconnect was trivial, even amusing at times. Local customs were generally unfamiliar to her. Once, on a visit to a fabric dyer with her sister, she was handed two rupees in change, which she planned to give back as a tip. Her sister’s sharp glare made her realize such a gesture would be insulting in this context.

The more profound sense of difference lay in language. While my mom speaks Urdu, hers is distinctly Americanized. Watching the news in Pakistan proved incomprehensible, and subtle changes in local dialects were difficult to decipher. Oftentimes she was told not to say anything in the markets, for her Urdu was tinged with an American accent and would make bargaining difficult, if not impossible. Added to this struggle was her tall figure, which made her a spectacle among family members.

To see a girl this tall was very uncommon. My cousins could not stop talking about it. And as soon as we started speaking Urdu, they would get such a kick out of it. They would repeat it back to us and just guffaw shamelessly, not even trying to hide it.

Ridiculed, my mom developed poor posture in an effort to downplay her height, and she avoided speaking Urdu in their presence. Her trip to Pakistan, marked by initial excitement, also revealed the complexities of navigating diasporic identity: the feeling of being caught between places, neither fully at home nor entirely foreign.

Back in Houston, my mom enrolled in political science, crafting her thesis on cultural imperialism. It’s interesting to consider how these colonial institutions offered her (and now me) a space to engage critically with the writings of non-white thinkers, to explore the intersections of identity as a racialized minority. She read Franz Fanon and Edward Said, was introduced to Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, and reveled in the revolutionary fervour of Che Guevara and Fidel Castro.

When you’re a minority or a perceived outsider, it’s very easy for you to see the other side of things. You have a much easier time disconnecting from the prevailing narrative. When you look at the shared collective grief that stems from oppression, you can identify with a lot of it.

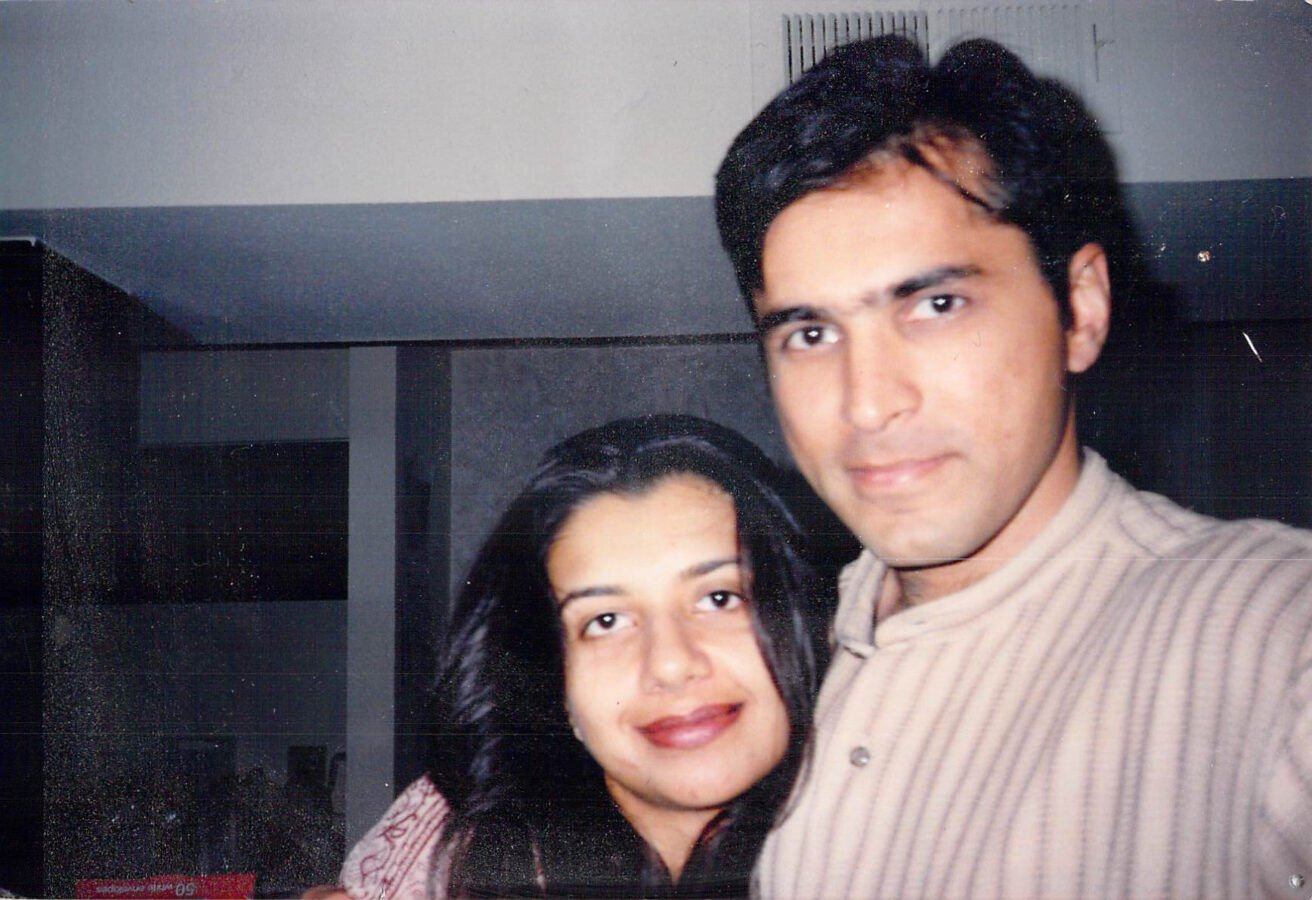

At 24, my mom got married, a seemingly inevitable act. The idea of not getting married didn’t seem to be an option, and the thought of marrying someone who wasn’t brown wasn’t even to be entertained; crushing on a white person didn’t feel physically possible. She remembers the release of Mississippi Masala and running into family friends outside the theatre. One of the aunties turned to my mom and sisters, exclaiming, “I hope you girls aren’t going to get any ideas from that!” The expectation was so ingrained, it would present itself in humour, racist undertones and all.

My mom married brown and Ismaili (extra brownie points) and later relocated temporarily to Peterborough, Ontario, to enroll my brother in a special needs school tailored to his cognitive and social challenges. Peterborough, a small and overwhelmingly white town, marked her re-entry into predominantly white spaces, this time as an adult.

It’s a different game. You come in with so many more identities you can use.

Her presence wasn’t simply defined by her skin colour anymore. It was shaped by how she carried herself, the credentials she could present, the choices she made for us. From her perspective, the Canadian ideal of pluralism—and its parasitic facade of multiculturalism—largely held true. The people we encountered in those early years fit the Canadian archetype: friendly and welcoming.

But the older I get, the more wary I am of that friendliness. Canadian multiculturalism does not strike me as a celebration of difference as much as a managed performance. The racism is still there; it’s just harder to name, buried beneath smiles and institutional politeness. Despite my skepticism, I’ve watched my mother become more forgiving, not only toward others but toward herself.

Everyone is skeptical of the other. I think it’s human nature to recognize patterns and to categorize things, right?

This isn’t an excuse for exclusionary behaviour, but rather an attempt to understand the instincts that lead us to draw lines around ourselves. Time and hindsight seem to have eased my mother’s self-criticism in the face of certain experiences, and resentment of her upbringing.

I was like any adolescent that wanted to blame my parents for everything. So I held a lot against them for a long time. But once you start having your own family, you recognize things, and you realize how hard it must have been for them. You think they’ve set these narrow boundaries for you, and you’re like, well, if you had just set them here [she places her hands a foot apart], I would’ve been fine, but they set them there [she brings her hands in closer], and I wish they hadn’t.

Then when you have your own kids and think you’re being so grand and gracious by setting the boundaries wider, you realize that’s not enough for your kids either. So, I see where they were coming from better now. It’s hard no matter what.

Such disagreements aren’t simply in direct opposition to culture. They may be prompted by a desire for something beyond just that, that referring to cultural origin. In my mother’s case, the boundaries her parents set felt constraining to her as a child, but growing up enabled her to recognize the weight of intentions behind them.

My Nana insisted on speaking Urdu at home, which was a point of contention in my mother’s youth, but is now a source of gratitude. From childhood to young adolescence, speaking Urdu felt restrictive. It wasn’t good enough for the streets of Karachi, but it also wasn’t good enough for home.

Who you are comes out in language. I didn’t have the vocabulary in Urdu to express myself fully, so I was quiet a lot.

This struggle for expression is something I think about often. Since I’ve picked up writing, I’ve been able to find these little pockets within the English vocabulary to express myself: words and phrases that speak to my frustrations, joys and laments. Writing serves as a means for me to explore the postcolonial spells I sleep under, the ancestral amnesia and collective anxieties that plague the peripheries of my psyche. In a way, too, it is a means for others in my life to be seen—those who shaped and made me, through the sides of them I see and the words that I hear.

But all of this reflection unfolds in the language of violence. A language that flattens Earth and consolidates truth. That severs tongue from memory and land, and disseminates disconnection. For all its cruelty, it gives me strange comfort—those worlds and words that sketched mine. It’s a comfort that borders on complacency. It’s easier to reach for English when exploring, even when it feels like resignation.

Urdu, by contrast, feels unmoored. I don’t yet have footing in that world… but I know it’s beautiful. In Urdu, to dream is not something you do, but something that comes to you. A dream arrives; there is a relationship to be built. And as I get older, I find solace in learning these small things.

As an adult, my mom, too, finds comfort in the growing body of Desi narratives that have emerged in recent years: chefs, writers and artists whose work reflects her own experiences in ways she didn’t encounter growing up. To come across stories interspersed with Urdu words stands as a small triumph for her. These narratives become places of familiarity, places to rest and cry and laugh.

As soon as you have a vocabulary for things, it makes them easier to deal with. Even nowadays, I come across these memes, and they’re hilarious to me because I’m like, yes, this is exactly what our mothers would say to us. To see them shared feels like an exhale; a collective acceptance of our experiences, a means of being seen.

I asked my mom if she still felt that old, lingering sense of not belonging. She paused, then answered—her voice calm, assured and clear—no.