Why didn’t I know?

It was the fall of 1984. I was in my first year of university and had a letter forwarded to me from my maternal aunt in Alberta: my estranged father wanted to reconnect. I had not seen him in 12 years.

“Je veux que mon fils, Marcel Naseer, rencontre sa sœur,” said the correspondence. I had a half-brother? His name was Marcel, like my cousin? How old was he? Why didn’t I know? My father was in Montréal. I was in Ottawa. I agreed to meet, despite my discomfort. What would we say to each other? Would he try to hug me? How should I react?

Mum was furious when I told her about the letter and the plan to reconnect. “Sa lettre dit clairement qu’il veut que son fils te rencontre et qu’il n’a aucun intérêt pour toi,” she assumed. Mum was bitter about the separation, divorce and their aftermath. The feeling of abandonment would follow her to her grave.

The day of the meeting arrived in October, in Ottawa, in front of the Faculty Club. My father had convinced an old friend of his, a professor at my university, to host us for lunch. I was nervous. “Ma fille,” my father said as he embraced me. My body stayed cold and stiff. I resented that he acted as if everything was fine after not seeing me for 12 years, assuming we could immediately jump into a normal father-daughter relationship.

Marcel was 11, I was 18. Given the age difference, my brother and I didn’t interact much.

Marcel was 11, I was 18. Given the age difference, my brother and I didn’t interact much. We were both uncomfortable and nervous. Marcel didn’t look me in the eye. He was silent and sat on the sofa, bouncing his head nervously against the backrest.

Our father was born in India. He came to Canada to do a Ph.D. and stayed. Marcel’s mother was German and had migrated to Canada in the 1960s with the help of my parents. My mother was French-Canadian from Alberta. She was my father’s first wife.

My parents had separated when I was a baby. By the time I was four, they had divorced. A nasty custody battle ensued, which my mother lost. She quickly whisked me off to Alberta and spent her meagre funds to put in place a reverse court order. My relationship with my father was therefore fraught and, for decades, I accepted her vitriolic depiction of him. As I got older, however, I started questioning, particularly after his death in 2016 and hers in 2022.

Within months of that reunification in October 1984, I attempted to cut off contact with my father and wrote him a letter saying that I could not handle the stress of seeing him. The butterflies in my stomach were constant. I couldn’t sleep or focus on my studies. Thoughts about how to handle my complex relationship with my father and distraught mother cluttered my mind.

My father responded with a tender handwritten letter and invited me to dinner, where he told me he should have never left my mother. That helped. But, when I did not come rushing back to him within a few weeks, he subsequently sent a cold, typewritten letter disowning me. I kept the letters for years until my mother convinced me to discard them. “Ton père voulait toujours gagner. C’est typique de lui,” she explained.

Ironically, my maternal grandfather had also written a letter disowning my mother when she announced her intention to marry my father—not because he wasn’t white, but because he wasn’t a Christian. As a Catholic, it was bad enough if you married a Protestant, but a non-Christian was a passport to hell! They eventually reconciled and I became close to my maternal grandparents.

After my father disowned me, I didn’t know if I would see my brother again.

After my father disowned me, I didn’t know if I would see my brother again. I was trying to find my way as a young adult, navigating the trials and tribulations associated with that time of life. In the years that followed, I dropped my father’s surname, connected with my paternal uncles, aunts and cousins in the USA but stayed clear of my father despite living three years in Montréal while doing my Master’s there. The years went by, and I moved to Vancouver in 1991 to do my Ph.D.

In March of 1993, my brother and I were coincidentally reconnected by a mutual friend, Normand. Marcel had mentioned to Normand—his classmate—that he had an older sister but didn’t really know her. Normand was able to put two and two together, as his own brother had taken courses from my father at university—a weird twist of fate. Marcel and I mutually consented to meeting through Normand on my next visit to Montréal.

The day finally came. Normand held me in his arms while I trembled, reassuring me that it would be okay. The impending meeting dredged up memories of the nightmares that had plagued me since I was four—when my mother started receiving subpoenas—and continued through our sudden departure from Montréal in 1972 and my father’s brutal rejection of me in the mid-80s.

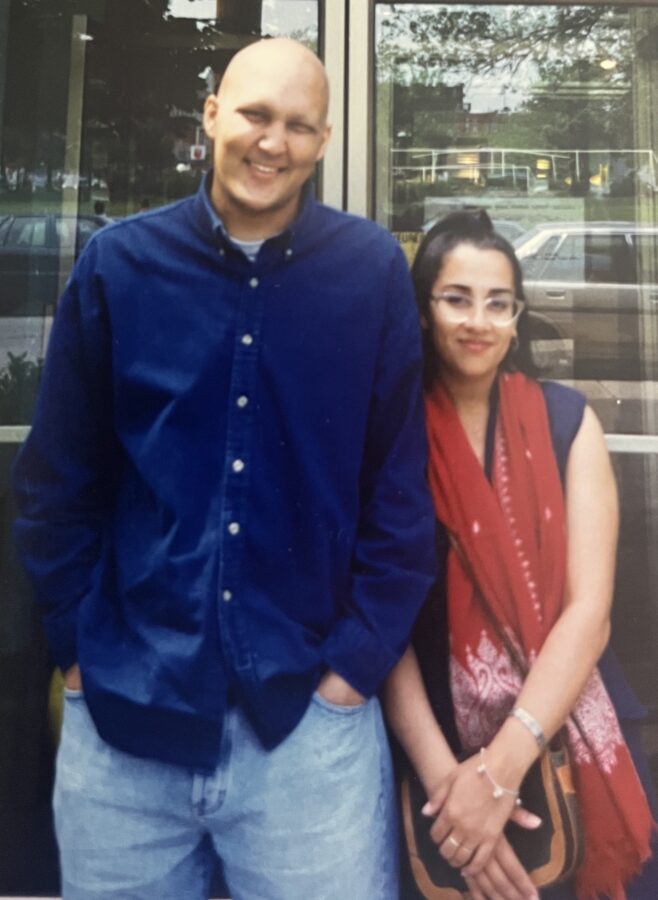

I walked into the room and Normand (re)introduced the two of us. My first thought was “who is that tall white guy drinking a beer?” I stood on my tippy toes and gave him a peck on the cheek. “Salut Marcel!” I said cheerfully. He spoke fluent French (and German) but preferred to speak English with me. We embraced and the discomfort wore off within minutes.

When I got a closer look, I could see how we resembled each other—both mixed-race and olive-skinned, the same eyes.

When I got a closer look, I could see how we resembled each other—both mixed-race and olive-skinned, the same eyes. Yet he also looked like his mother’s side of the family. “Il a le menton de son grand-père allemand,” my mother declared when I shared a photo of Marcel with her. Mum had known the family in Germany, which had added to the pain of my father’s betrayal: he had, ostensibly, left her for Marcel’s mother, whom she had considered a friend. After my father died, I kept in touch with Marcel’s mother and visited her regularly until her death during COVID-19. I then learned her side of the story…

It was overwhelming yet exhilarating to meet a tall young man of 19 who was studying at university. We hit it off immediately, the conversation flowing naturally as we compared notes on our quirky father and talked about life, friends and studies. We committed to keeping in touch. “I’ll write to you often,” I promised Marcel.

While I wasn’t ready to reconnect with my father, I finally had someone to relate to with respect to our shared paternity. I also had the privilege of getting to know this unique, gentle soul and trying to understand what it meant to have a sibling. My heart was full of love for this “foundling” brother with his gentle spirit. I was elated.

I kicked off our correspondence with a heartfelt letter in March 1993 to express how thrilled I was to be connected to my six-foot-tall “little brother.” The tensions with my estranged father were evident and I was unsure of how to approach the topic of my relationship with him in our exchanges—a challenge that persists more than 30 years later. But my enthusiasm for my newfound brother was palpable:

As far as you are concerned, dear brother, I’m very anxious to make you a part of my life. You are a delightful, intelligent and mature person and I’m proud to be related to you! You seem much more in touch with your emotions and serene than I was at 19. I told my mother all about you and our two meetings and she was very happy about it. She would be happy to meet you sometime as well. We can talk about it next time I’m in Montréal.

A flurry of correspondence flowed in the 20 months that followed, between Montréal, Vancouver and Bangkok, where my research was taking place. My tone was a bit officious, preachy and lecturing, as I immediately relished the opportunity to give unsolicited advice to a younger sibling. Marcel’s missives and the life they reflected were typical of a young fellow that age: they revolved around his studies, part-time job, friends, love life and aspirations to become a photographer.

Marcel even paid me a visit in Vancouver for a few days in the summer of 1994, on his way to and from a snowboarding trip to Whistler. I was beyond chuffed to finally have a sibling, as I had thought of myself as an only child until then. And the door opened a bit more, allowing me to get to know my mysterious and complicated father.

December 1994 while I was in Bangkok was a major turning point. After 10 years with no contact, my father emailed me to break the news of Marcel’s cancer diagnosis. At the time, they thought it was Hodgkins, but this diagnosis would later evolve into germ cell cancer. I immediately called Marcel—who was in shock, yet stoic—and spoke to our father—our first conversation in 10 years. The interaction was brief and focused on Marcel.

I then penned my “still new little brother” an aerogram on December 5, 1994, to try to lift his spirits. Fortunately, my plan was to return to Canada soon, so I scheduled a visit to Montréal.

I just found out about your illness a few days ago—here’s a long letter, which I hope will cheer you up and give you strength. Understandably, you sounded quite shook up on the phone. Please believe what the doctors told you—you will be cured very soon. I talked to my mum (I hope you don’t mind, she is a nurse). She said that Hodgkins has been very successfully treated for many years now. My own limited reading on cancer treatments has indicated to me that there is something to be said about keeping a positive attitude because mind over matter works. This must sound unbearably preachy and highhanded to you—sorry! I just want to try and give you a boost of confidence.

My letters became frequent and motivational. Marcel began a diary to chronicle this new, unexpected journey. Below is an excerpt from his first entry, dated December 14, 1994:

It seems life throws you some fast balls sometimes. You don’t really have time to react. You just go with it. That’s what it’s felt like in the last three weeks. I don’t feel un-lucky for some reason, these things just happen. It’s just unfortunate that it has happened to me.

I lived a healthy or somewhat healthy lifestyle. I never thought once of getting cancer, especially at this age. I’ve been home for a week and I feel much better. I feel a bit stronger every day. Tonight, I actually went out and had two beers with Marc C at the Clandestin. I also attempted to write my camera and light exam, but who was I kidding. I couldn’t remember anything. I will have to take it again.

Being sick has made me realize how many good friends I have, the number of cards, calls and letters I’ve received have really helped. Jake’s dad is even sending me these self-healing tapes from some guru. I can’t wait to listen to them. I’ve started to really question western medicine. Maybe these will give me a new outlook.

Gisèle is coming to visit a few days before Christmas. I’m looking forward to seeing her. I’m so proud of her. She’s so together. She’s strong. I could learn a lot from her.

It’s odd for me, now, to read how Marcel perceived me as “together and strong”. Nothing was further from the truth at that time in terms of my own internal struggles and concerns about where my life was going. The voices swirling around in my head were full of angst: “What is happening with my career? Should I marry and have children?” Typical tormented twenties…

Our correspondence and Marcel’s diary entries continued unabated, at first filled with hope but by the summer of 1995, increasingly bleak. My final letter to Marcel—unbeknownst to me at the time—was dated August 28th and had a cheerleading tone following my visit to him in the hospital in Montréal and my return to Vancouver.

Coincidentally, this was the same date as Marcel’s last diary entry, with his first paragraph summarizing the pain and weakened state he was in. The entry provides such a stark contrast to the fit, active young man I had come to know before his illness:

I’m really dazed right now. I’ve taken a lot of pain killers. I have real trouble keeping my eyes open. I have weird dreams. I have to keep reminding myself what’s real and what’s a product of my imagination.

And my last note from Marcel, with no date, following my visit to the hospital in late August:

I’m glad you guys came by. I’ve never felt this weak in my whole fucked-up life.

I can’t walk w/o supervision.

By early September, Marcel’s health had deteriorated further. There was no hope for recovery. I called him and spoke gently and lovingly, saying, “There’s something that we don’t understand that happens after we die. Energy can neither be created nor destroyed. Somehow, we’ll meet again, little brother.” He was frightened and cried, but this seemed to offer him comfort. I was speaking from the heart and he appeared to believe me. Did it help him let go?

Our Muslim-turned-atheist father did not hold spiritual views, at least not at that time. Nevertheless, when a memorial service for Marcel was held in the Catholic church behind the family home, my father wanted the most important prayer in Islam—the Fateha—recited by one of his students who, sadly, never showed up.

I attended the service and tried to comfort my father and his wife and cooked them a Thai meal. “Your father refuses to eat leftovers, so we’d better finish everything,” his wife said to me. “C’est délicieux,” praised my father, finishing off his plate.

Marcel died on September 11, 1995 at 2 a.m. local time in Montréal. I was in Vancouver and was the first person my father called.

Marcel died on September 11, 1995 at 2 a.m. local time in Montréal. I was in Vancouver and was the first person my father called. Marcel had just turned 22 the month before. For years, I remembered the date of his death, but by the time I started writing my memoir, I had forgotten. I even wrote to his oncologist who, naturally, no longer remembered Marcel. I thought I would have to write to the Directeur de l’état civil du Québec to request a copy of his death certificate but through a stroke of luck, I found my own journal from that time, with the date clearly indicated.

There is no record of Marcel’s existence in the cybersphere beyond the “Marcel Naseer Ali Memorial Lecture in Aquatic Biology” at the University of Guelph, endowed by our late father despite the fact that his career was in Montréal. My brother had no interest in aquatic biology. He liked photography, snowboarding, photography, girls, smoking pot and hanging out with his many friends. I can’t even find an obituary for Marcel. Nowhere. It’s like he didn’t exist.

My father wanted to become a part of my life again after Marcel passed. I tried, but couldn’t cope—partly because of the pain I knew he had caused my mother and partly because of my own unresolved traumas. “Il nous a abandonnés quand tu étais bébé et t’a à peine regardé le jour de ta naissance,” she would say. “Je me suis débrouillée toute seule pour t’élever. Il a l’audace de se pointer le nez maintenant que c’est clair que t’es une « trophée » pour lui,” she would recall bitterly.

When my own son, Marcel, was three, he asked me “Maman, c’est qui ton papa?” I felt obligated to reconnect. We then rekindled the relationship somewhat, much to mum’s chagrin.

While my father was on his deathbed in 2016, his wife called and offered to buy me a plane ticket from Vancouver to Montréal. “Is he conscious?” I asked her? The answer was no. I declined her offer. He died in November 2016. His last words were, “Où est Gisèle?”

I keep a photo of Marcel near my bedside. It’s a reminder before I fall sleep and when I wake that I have the gift of life. His time on this earth was far too short. I became a full-fledged adult, travelled the world, got married, had a child and an exciting career. He had none of that.

But he did have a relationship with our father, who loved and clearly wanted him. Whereas I have very few photos of me with my father as a child, I have inherited albums full of happy-looking images of my brother with our father. A tinge of jealousy surfaces when I look at these pictures.

Marcel Naseer Ali’s life mattered. It mattered to me, to our father, his mother, our mutual extended family and his friends.

Marcel Naseer Ali’s life mattered. It mattered to me, to our father, his mother, our mutual extended family and his friends. I was proud to call him my brother. I struggle to assemble our letters and his diary entries and craft a narrative around them for the sake of those who were blessed to know him, as well as for my son, Marcel—now 22 himself—so that he might learn something about the uncle he will never know.

I also continue to untangle my own feelings and emotions about a sibling relationship that, while brief, helped me learn about myself and our father, who died with regrets. I now realize our father loved both of us in his own way.