Introduction

Since the 1980s, Bhils in the Alirajpur district in Madhya Pradesh, India have been organizing under the Khedut Mazdoor Chetna Sangat, an independent trade union, to revive their customary way of life and restore the ecosystems of their traditional lands.

This article outlines how the Bhils’ experience suggests that ecological agriculture combined with forest, soil and water conservation, renewable energy generation and local agricultural processing that forms a local communitarian circular economy can comprehensively tackle both poverty and climate change.

The world is burning

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions caused by anthropogenic (human) activity have resulted in a 1°-Celsius increase in ambient temperature worldwide since 1945, and temperatures continue to rise 0.2° C every decade. This continuous rise in temperature is bringing dramatic changes in climate that will threaten the existence of life on earth.

The United Nations Conference of Parties organized in Paris in 2015 (COP21) called for limiting the ambient temperature rise to 1.5° C from the time of the Industrial Revolution, a threshold beyond which the negative impact of climate change could be dire. We have already crossed this threshold.

Currently, the world GHG emissions are 55 billion tonnes of CO2e (Carbon Dioxide Equivalent) annually, while the total amount of carbon sequestration, mainly through forestry, is only two billion tonnes of CO2e. If human-induced climate catastrophe is to be averted, we must both urgently transition away from fossil fuel to renewable energy and increase sequestration through various carbon removal methodologies, principally afforestation.

Agriculture, too, must transition—from chemical farming to ecological methods—to reduce GHG emissions and to ensure biodiversity, soil health and water availability (Shiva, 2015). The local and global commons are in jeopardy, and the best way to defend them and sustain humanity is to strengthen communitarian conservation initiatives (Ostrom, 1990). For four decades now, the Indigenous Bhil people of the Alirajpur district of Madhya Pradesh in India have been doing exactly that.

Traditional Bhil society

The Bhil Adivasis (“original inhabitants”) of western India are the most populous tribal grouping in India. Traditional Bhil culture is communitarian; that is, the community rather than the individual is of primary importance. The Bhils practised a subsistence economy that ensured sustainable use of their natural resource bases (Deliege, 1985) in the hilly and forested areas of southern Rajasthan, eastern Gujarat, western Madhya Pradesh and northern Maharashtra where they live. Important characteristics of traditional Bhil society include:

- settlements of small communities linked together by strong kinship ties

- a subsistence-based, non-accumulative and non-monetary economy heavily dependent on customs of labour pooling in all social and economic activities

- a system of interest-free loans in cash and kind

- a high dependence on forests for meeting daily needs as well as long-term agricultural needs

- minimal interaction with the external, centralized trade-based economy

- social customs that ensure the redistribution of individual families’ surplus among the community and as a thanksgiving to nature

- fierce defence of their habitats, which are crucial to their existence. There is historical evidence that, thanks to their superb archery skills, the Bhils successfully defied the Gupta emperors to retain their independence (Kosambi, 1956).

Significantly, accumulation of goods, trade and monetary profit had a minimal role in traditional Bhil society, which continued for centuries at a low-level resource-use equilibrium. The Indal festival plays an important role in this economy. Celebrated every five years or so, the festival uses surpluses from farming and other activities to provide a feast for the entire community. Indal not only provides thanksgiving to nature and the community, which make every household’s living possible; it also ensures egalitarianism and non-accumulation by distributing the surplus to the community. This tradition presents an important contrast to the excessive accumulation in the mainstream economy that is at least in part responsible for the present severe ecological problems we are facing throughout the world.

Colonialism, the Indian State & grassroots organizing

Colonial British rule and subsequently the independent Indian state devastated both the Bhils’ habitat and their cooperative communitarian society. Corporations seeking to extract resources made inroads into the Bhil homeland, leading to their socio-economic marginalization. Poverty became endemic, such that most households were no longer able to celebrate the Indal, as they no longer had any surplus to distribute.

From the 1980s onwards, however, teaming up with activists from outside the district, the Bhils of Alirajpur district in Madhya Pradesh have organized themselves in a trade union, Khedut Mazdoor Chetna Sangath (KMCS), in order to revive their traditional communitarian culture and restore and conserve their habitats and farms (Banerjee, 2008). Not only did the KMCS re-establish the rights of the Bhils over their forests, even more importantly, it leveraged their traditional customs of communitarian ecosystem preservation and restoration that had fallen into disuse due to repression, first by the British colonialists, then by the agencies of the independent Indian state. These traditional customs were and are key to the Bhils’ success rejuvenating their forests, soil and streams.

Further, in the 1990s in western India, the Bhils formed the Adivasi Ekta Parishad (AEP), a forum of Bhil grass-roots organizations. While upholding the positive aspects of traditional Bhil culture such as its communitarian focus, the AEP critiques aspects of this culture, such as patriarchy and witch hunting, which are detrimental to its future, and favours synthesizing traditional Bhil culture with modern education and skills. This synthesis helps the Bhils in their struggle to maintain their identity in the modern polity and their economy as a distinct community. It also offers leadership in confronting the challenges of sustainable development facing humanity more globally (Banerjee, 2014).

Communitarian ecosystem restoration

Thanks to their communitarian modes of ecosystem preservation and restoration, the Bhil Adivasi members of the KMCS are contributing immensely towards mitigating the root causes of climate change. Their frugal way of life and ecological agriculture creates minimal GHG emissions, all the while sequestering carbon through afforestation and soil and water conservation.

The Dhas custom of labour pooling

Labour pooling is the most important aspect of Bhil society. It enables the community to undertake considerable work by coming together. One member from each household contributes labour to some activity of another household or of the community. No wages need to be paid, and everyone benefits. The absence of money also results in less consumption, which too reduces emissions. These two characteristics of communitarian cooperation and frugal living are the key to the Bhils’ work in ecosystem restoration.

Protection and regeneration of forests

The Bhils rightly believe that it is better to protect and regenerate forests than to plant saplings from nurseries. This is especially important given the local climate. In the high summer heat of the Narmada valley where the Bhils live, small saplings mostly die due to the heat and a lack of water for their tender roots. In contrast, shoots coming out from the deep roots of existing trees are far hardier and easily survive.

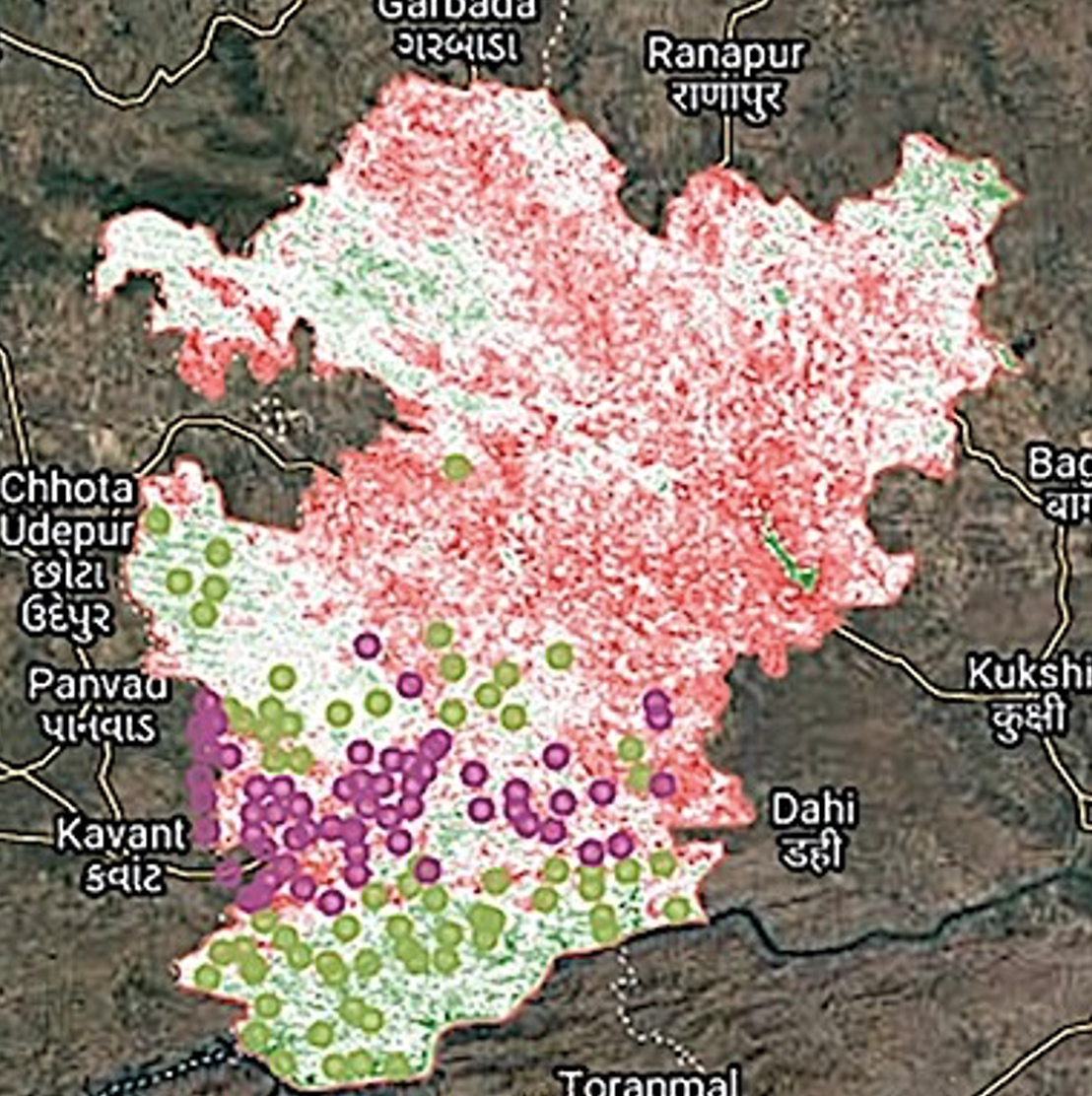

With this understanding of their forests, the members of the KMCS trade union first began protecting forests through collective action in the mid-1980s. Women took the lead in this work, forming protective groups. Grazing was prevented and the grass that was thus able to grow was harvested in winter for the livestock. The forests were sustainably harvested and the wood used for construction. This strategy meant that a growing forest could thrive—the best way to sequester carbon. Later, other villages successfully adopted this communitarian practice. There are currently 70 villages with 13,000 hectares of forest land between them. In fact, one village, Amba, on the banks of the River Narmada, maintains forests on as much as 60% of its total land. The remote-sensing map below shows how KMCS-supported communitarian initiatives have led to increases in overall vegetation cover.

A more detailed analysis of Landsat data with a higher resolution (900 m2 per pixel) than the above map revealed that vegetation increased not only in the KMCS villages but even in the control villages over the three decades studied, even though there are no dense forests near these villages. Overall, the KMCS initiative has had an impact on the whole of Alirajpur district, inspiring the residents to protect trees. The significance of this achievement for climate change mitigation strategies cannot be overstated. It shows how attitudes and practices from a grassroots initiative can spill over and influence attitudes and practices of people not directly involved in the initiative.

Bunding and gully plugging

The Bhils use their labour-pooling customs very effectively when undertaking soil and water conservation work on their hilly farms and the surrounding hillsides. They mainly use stones for bunding (building and repair of retaining walls) on their farms and for plugging the gullies that border their farms. This labour-intensive, collective work is essential for maintaining and managing thousands of hectares of agricultural land. See Gravity-based irrigation below.

Ecological agriculture

The Bhils are default organic farmers. Traditionally, they have used only manure and their own vast cornucopia of heirloom seeds in their farming. Indeed, their main goddess is Kansari, who is symbolized by the cereal sorghum. Their creation myth recounts how God, after creating the lifeless human form, asked it to suckle at the breasts of Kansari to get life. Just as sorghum is an important crop, Kansari is a much-worshipped goddess among the Bhil people.

Energy efficiency

Research has shown that ecological arable production is about 35% more energy-efficient per unit of output than chemical production (Smith et al., 2015). Since ecological farming techniques don’t disrupt soil pH, the use of energy-intensive lime is non-existent, resulting in lower CO2 emissions compared to modern external-input farming techniques. The use of organic matter also increases carbon content in the soil, storing up to 75 kgs of carbon per hectare per year. Additionally, ecological farming uses nitrogen-fixing plants as cover crops and during crop rotation, helping to fix nitrogen in the soil. Moreover, bio-gas plants can channel methane for cooking and generation of electricity. Finally, soil micro-organisms further oxidise methane and sequester carbon.

Reduced contribution to global warming

The combined effect of all the different benefits of ecological farming results in a global warming potential that is only 36% that of modern external input chemical farming. The main constraint to ecological farming is the availability of adequate amounts of manure, as the dung produced is insufficient for the fertilization of all areas under seed. This problem of shortage can be solved by composting animal manure with a mixture of waste agricultural and forest biomass and by making microbial cultures out of dung (TNAU, 2023).

Reduced water use

Ecological agriculture with indigenous seeds is less water-intensive than external input agriculture. The virtual water (water consumed during growth that the harvested crop carries away from the growing location) embedded in these indigenous seed crops is less than that in crops grown with modern methods (Hoekstra & Chapagain, 2007). Consequently, traditional, indigenous seed-based agriculture greatly reduces water use and relieves water stress. Thus, by combining their organic agricultural methods with appropriate soil and water conservation measures—beginning with the uppermost ridges of river valleys and working down to the drainage lines—the Bhils are ably mitigating climate change.

Gravity-based irrigation

The Bhil Adivasis have long maintained very robust local water-use systems; these are still extant despite the spread of diesel- and electricity-powered irrigation systems (Rahul, 1996). Their extensive forest, soil and water conservation work has increased the availability of water for farming, and they continue to use—and develop—these systems to work towards overall water and energy sustainability in the areas where they live and farm.

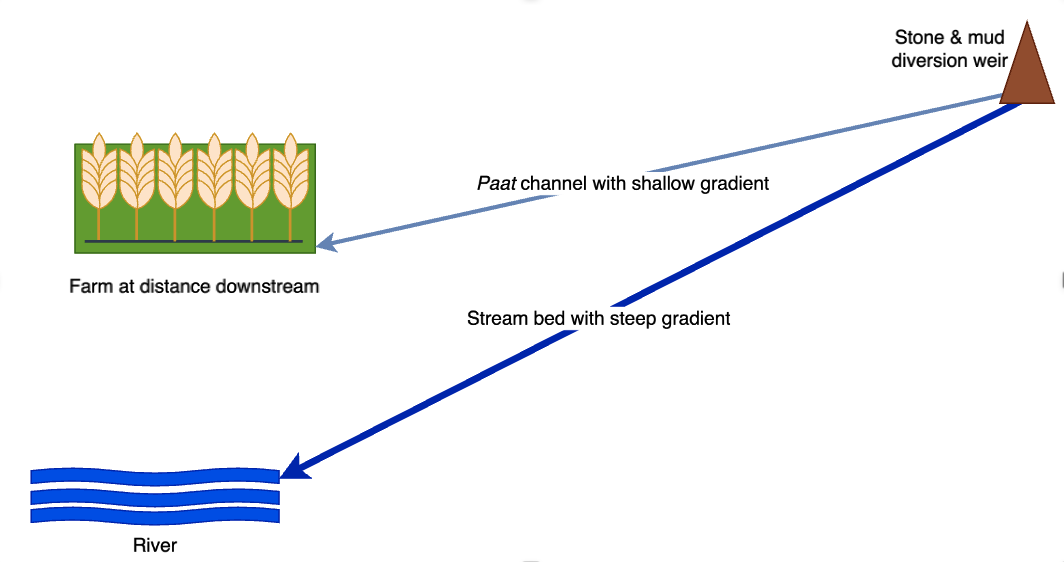

Interior villages of western Madhya Pradesh employ a water-use system that appears to make water scale steep hills to irrigate fields. This seeming defiance of the law of gravity is in fact a system devised by the Bhils that takes advantage of the peculiarities of the hilly terrain to divert water from swiftly flowing hilly streams into channels called paats.

During the last four decades, the Bhils have been developing and refining this paat system. This practical and ecologically sound method of water management can be interpreted, not just as sound water management practice, but also as the Bhil Adivasis’ retort to the Indian state’s destructive practices that have ravaged the region’s environment.

The paat system works on the principle of differential gradients. The stream bed itself has a steep gradient. The stream is bunded with stones and mud at an upstream point well above the farms in the village. This bunding creates a diversion weir. A paat channel taken off from the weir and running alongside of the stream is built with a much shallower gradient than the stream’s such that, as the stream progresses downstream, the channel gradually gains in elevation with respect to the stream bed. The diagram below represents a paat system.

The crucial decision when building paat systems is determining exactly at what point upstream from the farms to build the diversion weir and the paat channel so that the channel and the water it carries reaches the farms. One of the Bhils’ great achievements is that they are able to successfully pinpoint this location without the use of any measuring instruments.

Notably, the people of Bhitada village located at the confluence of Kari, a stream, and the Narmada River in Alirajpur district, have developed this system to possibly its best form. Even though the bed of the Kari at its confluence with the Narmada is positioned about 20 meters below the farms on its banks, the fields are lush green with maize and gram (chickpea), grown with water brought by a four-kilometre-long paat from a point upstream whose elevation is higher than that of the fields.

After the kharif (monsoon-season) harvest of bajra (millet) and maize, one member from each Bhil family is spared to join others to rebuild and repair as necessary the water channel and the diversion bund. It takes about two weeks to get the paat flowing and ready for the winter crop sown in early November. The process is quite a laborious one. The diversion bund across the stream is constructed by piling up stones into a wall, which is lined with teak leaves and mud to make the structure leak-proof. The paat channel has to steer through the nullahs (deep ditches) that join the stream before reaching the fields. Stone aqueducts to span these nullahs are built in a manner similar to the diversion bunds. Particularly noteworthy is the skilful manner in which the narrow channels have been cut in the face of the sheer stone cliffs.

Even when it has been meticulously designed, built and repaired, a paat channel requires constant maintenance; it is the duty of the family irrigating its fields on any given day to take care of the paat for that day. This communitarian effort, from the construction to the maintenance of the paat, not only supports the village’s agriculture and, hence, its life; it also binds the whole village together, while at the same time conserving the environment.

Framework for socio-economically equitable & ecologically sustainable development

The United Nations has declared the 10-year period from 2021 to 2030 as the decade of ecosystem restoration (UN, 2023). The Bhil Adivasis, however, have been practising ecosystem preservation and restoration since time immemorial, and in the case of the KMCS members in Alirajpur district, they have successfully revived their traditional customs to effectively improve both the ecosystem and their livelihoods (Banerjee, 1997). This success suggests that the Bhil ethic of equitable development would serve us all well if adopted for large-scale projects to help solve the ecological crises humanity is facing. And, considering the leadership role KMCS women have assumed in Bhil initiatives to protect and regenerate their forests, this development model empowers women to claim their decisive role in society and the economy.

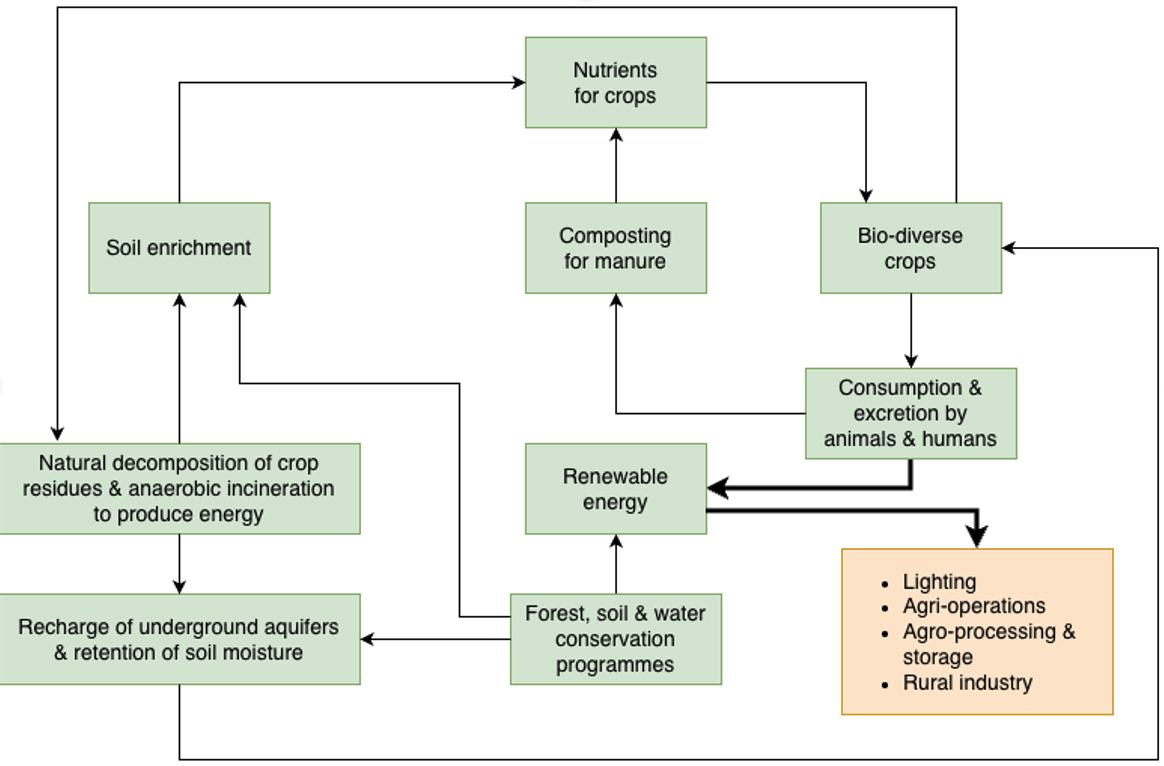

The Bhils have shown that ecological, internal-input agriculture combined with forest, soil and water conservation, distributed renewable energy generation, and local agricultural processing constituting a local communitarian circular economy can comprehensively tackle both poverty and climate change. The framework for achieving this is schematically shown in the figure below.

The traditional Indigenous Bhil way of life and culture are respectful of nature, in contrast to the modern state system and the market economy that are increasingly proving to be detrimental to both nature and human survival. The wisdom of the Bhils has a great deal to offer human beings across the planet. As individuals we cannot bring about radical change on our own; what is required is collective action by communities at the grassroots level.

References

Banerjee, R. 1997. “Reasserting Ecological Ethics: Bhils’ Struggles in Alirajpur”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 27 No. 51-52.

____. 2008. Recovering The Lost Tongue: The Saga of Environmental Struggles in Central India. Hyderabad: Prachee Publications.

____. 2014. “Impacting Development Thought and Practice through Bhili Cultural Rejuvenation”, e-Vani: The Voice of the Voluntary Action Network of India, 10(4):13-20.

____. 2024 “Communitarian Ecosystem Restoration: A Timeless Gift from Nature Worshipping Bhil Adivasis”, mahilajagatlihazsamiti.in.

Deliege, R. 1985. The Bhils of Western India: Some Empirical and Theoretical Issues in Anthropology in India, Delhi: National Publications.

Hoekstra, A. Y. and Chapagain, A. K. 2007. “Water Footprints of Nations: Water use by People as a Function of Their Consumption Pattern”, Water Resources Management 21(1): 35-48.

Kosambi, D. D. 2016. An Introduction to the Study of Indian History. New Delhi: Sage Publications India.

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rahul. 1996. “The Unsilenced Valley”, Down To Earth, June 14, 1996.

Shiva, V. 2015. Violence of the Green Revolution: Third World Agriculture, Ecology and Politics. University of Kentucky.

Smith, L., Williams, A., & Pearce, B. 2015. “The energy efficiency of organic agriculture: A review”, Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 30(3), 280-301.

TNAU 2023. “Preparation of Organic Manure.” Tamil Nadu Agricultural University at: https://agritech.tnau.ac.in/org_farm/orgfarm_manure.html accessed on 10.01.2024.

UN, 2023. “Decade of Ecorestoration” at: https://www.decadeonrestoration.org/, United Nations Organisation, accessed on 10.01.2024.