This piece is based on an interview I conducted with my grandparents, Errol Sears and Maylene Yamin, in November 2024, in their living room in Montréal. All photos are from our family albums.

Somewhere by the silt-tainted coast of Guyana’s capital, my grandma was born in her family home in May 1950. Her parents were primarily of Indian descent, though her great-grandfather was said to have migrated from Nepal. Like most little girls, she had a streak of mischievousness that sometimes landed her in trouble with her mother. She recounts a time when an imam sent her home to ask her parents what her Muslim name was—as Maylene Yamin was not sufficient—only for her to buy ice cream at the corner store instead and return with the lie that her name was Zubaida.

My grandma was raised in a Muslim household but attended the nearby Roman Catholic primary school, where she participated in elaborate activities like yearly mock coronation ceremonies. Her childhood was one of play, running down streets and inventing new hobbies with her siblings. One of her favourite games was Chinese checkers, of which she remains the undefeated champion in our family. Her board was tucked under the coffee table as we spoke, marbles from a forgotten game scattered about.

Further west of Georgetown—where the tumult of the city made way to the crooning of herons and the sway of tall grass—my grandpa was born seven years earlier in the village of De Kinderen. He was baptized as a Presbyterian Christian by the name of Elmo Sears, but he chooses to go by Errol instead, to avoid the chagrin of being compared to that little red puppet. His childhood was spent moving between Uitvlugt and De Kinderen by donkey cart, as his father alternated between being a tailor and working on plantations. It was only when his father was promoted to assistant field manager that the Sears family settled in the compound on the sugar estate in Uitvlugt.

Life in the village was just as much about catching bumble bees and flying homemade kites as running from a cane stick.

As a child, my grandpa would help the missionary, Miss Anderson, try to convert the Hindus and Muslims in the village every month. He describes this activity as being a social event, however, where the teachings of Christ were secondary to the drinks and gatherings. Like many children around him, much of his childhood could be characterized by the physical abuse experienced both at home and in school, though he recounts these incidents with his distinctive dry humour. Life in the village was just as much about catching bumble bees and flying homemade kites as running from a cane stick.

My grandpa’s father, Wilfred Sears, (front row, third from the right) with the staff at the Booker’s sugar estate in Uitvlugt, Guyana, 1940s. He was one of the first locals to be promoted to a senior position.

My maternal grandparents shared their early years with me in their living room, photographs sprawled out on the glass table. They were content to speak for hours on everything from politics to family to food. My grandpa took my request for an interview rather seriously, having come prepared with a series of notable locations on Google Maps and videos of the old Booker’s sugar mill in motion. My grandma, meanwhile, spoke very much ad libitum, even getting up in the middle of the recording to make food or tea. I feel that their differing approaches to the interview are charmingly indicative of their personalities, and having them recorded together captured the chemistry that I so admire between them. They would sometimes correct the other if they misspoke, fill in the other’s blanks or even bicker with each other.

Grandpa [overlapping]: Yeah, for months and months and months, like, you’re depressed.

Grandma: Not depressed-

Grandpa [jokingly]: Me!

Grandma: Oh! Well you talk for yourself.

Until now, much of what I knew about Guyana came mainly from my father, whose experiences were far different from those of my maternal grandparents, having been born post-independence and into different economic, political and familial circumstances than they had been. Given this generational discrepancy, I had never been told about the 1960s or the political unrest that my grandparents recall witnessing. With supplementary research I conducted after the interview, a colonial-era Guyana was coming into view.

The tumultuous sixties

Both of my grandparents’ lives in Guyana culminated with the political outbursts of the early 1960s. They specifically name 1963 as a turning point and refer to it as if it were a single occurrence, but these events transpired over years in different areas to varying degrees of violence. Being on the cusp of independence, the first half of the 1960s was characterized by strife, spurred by a combination of internal and external influences. As my grandpa puts it, the elections were essentially a “vote for your own people” system. Most of the Indian population was loyal to Cheddi Jagan’s People’s Progressive Party (PPP), the African population to Ford Burnham’s People’s National Congress (PNC) and the Portuguese population to the United Force (UF) (1962 Report). It was becoming clear that whoever won the upcoming election would be the first to lead the country into independence and shape its trajectory for the foreseeable future (Ralph R. Premdas, 31)

In the face of Jagan’s popularity—which was unsurprising, given the minority-majority status of the Indian population—the PNC and UF formed an oppositional coalition. Though the lack of sources and the contentious nature of the situation make it difficult to produce an objective analysis of what was transpiring on the level of government, Ralph Premdas argues that the violent 1962 labour strike in Georgetown was instigated by the opposition to frame the PPP as unsuited to govern the country and postpone the independence deal with Britain. The 80-day strike in 1963 began in the same way, headed by the Afro-Guyanese majority Trades Union Council, which was supported by the American Federation of Labor, the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions and foreign-owned bauxite and sugar companies (Premdas, 29-33).

My grandparents ascribe the schism between the Afro- and Indo-Guyanese populations to the watershed events in 1963

My grandparents ascribe the schism between the Afro- and Indo-Guyanese populations to the watershed events in 1963, stating that there had previously been no animosity between them and that this unrest did not affect their relationships with their Afro-Guyanese peers. They also attribute this division to the divide-and-conquer tactics employed by colonial forces, with my grandpa drawing specific parallels to the threat that Cuffy once created for the Dutch by heading a slave uprising.

It would be misleading to characterize this discontent as stemming exclusively from beyond the realm of the Indian population, however. Class divisions along ethnic lines are also worth considering. My grandma mentions that the Indian and Chinese populations owned most of the businesses and would rent to many of the African descendants identifying what appears to be an ethnic-class demarcation.

A British commission on the 1962 strikes observed the same pattern, noting that many Indian descendants entered higher-paying professions in medicine, commerce, law and civil service (1962 Report, 7). Perry Mars argues that the interconnectedness of ethnicity and class played a role in these events, which were already underway before the strikes began (88). Without denying my grandparents’ claims of bearing no ill feelings toward their Afro-Guyanese neighbours, their attitudes are not representative of an entire population and their personal feelings do not belie systemic imbalances.

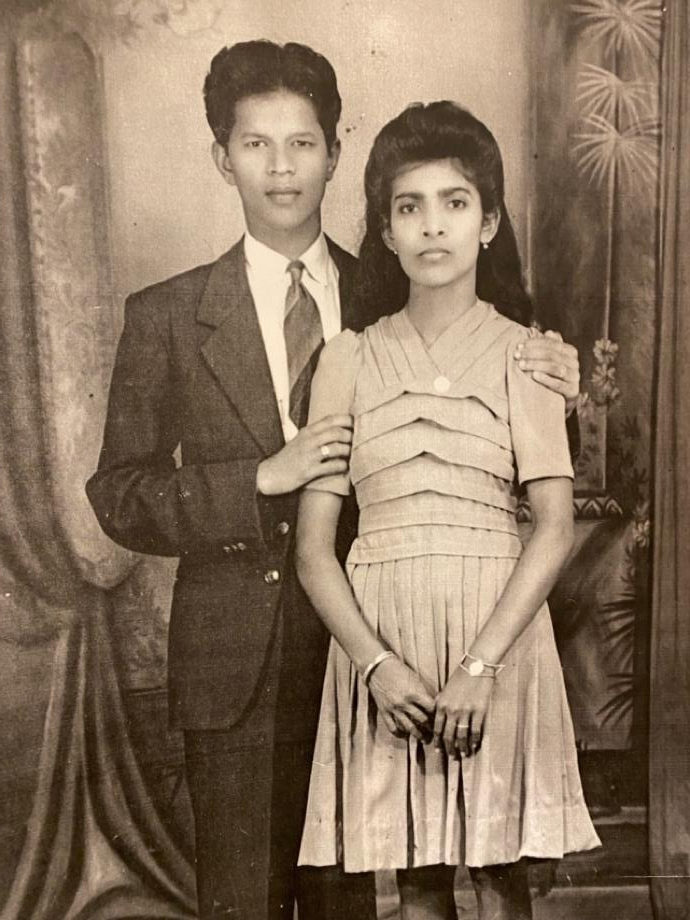

Immediately following these events and just before Guyana’s independence, both of my grandparents moved to England. Though it was common for parents to send their children abroad in this period (D. Alissa Trotz, 290), their migrations appeared to have other motivating factors. My grandma’s father was already settled in London by this time, and she was one among many siblings on their way to live with him. Meanwhile, my grandpa left to study in England, where he shared a single-room apartment with his brother until he and my grandma got married in 1970, a few years after first meeting each other’s gaze at Victoria Station. They would go on to have three children, two of which were born before they finally moved to Canada at the request of my grandpa’s sister, whose husband had found a job in Québec’s heavy industry.

“Double diasporics”

Although I shared most of my interview questions with my grandparents in advance, I refrained from telling them that I would ask for their “ethnic” or “racial” identity. I was interested in seeing how they might respond without having the liberty to ruminate. As it happens, they gave me fluctuating responses that I believe reflect their social realities as members of a double diaspora (“double diasporics”), or people whose histories could be linked to two primary locations outside of the one they currently inhabit.

In answer to my question, my grandma replied with an immediate and resolute “Indian.” My grandpa instead said “West Indian.” After some deliberation, both settled on calling themselves Guyanese.

Interestingly, my grandpa considered the “Guyanese” and “West Indian” labels from the perspectives of outsiders. He felt that many West Indians might not consider Guyana part of the West Indies because of its geographical position in South America, and because Guyana is historically, culturally and linguistically an outcast among its South American neighbours. In considering his relationship with Guyana, he said: “I keep saying I’m Guyanese, but if I go to Guyana, they’re gonna insult me.” When my grandma asked why, he replied: “They say, Wha you come here for?”—implying that locals would consider him to be as much of a foreigner as someone who had never lived there at all.

Having spent my whole life in Canada, I never doubted the validity of my grandpa being Guyanese.

Having spent my whole life in Canada, I never doubted the validity of my grandpa being Guyanese. I realize now that the legitimacy of that connection might waver in his process of self-identification, as a migrant who has only visited his country of birth once in the past 69 years. Spending six decades in a country is not enough to qualify either, however. Using humour, he illustrates his relationship with the “Canadian” label by presenting how he would react if he were attending a comedy show and the comedian asked who in the audience was from Canada. My grandpa would only raise his hand halfway so that the people around him wouldn’t notice.

By way of the looking-glass self, my grandpa’s self-identification appears to be informed, at least in part, by his beliefs about how others perceive him—typically in the sense that those who are part of the group with which he might identify would reject him for being too visually or culturally different (Aliya Saperstein, Andrew M. Penner, 187). It seems that “Guyanese” provides not only what they perceive to be the most accurate label for themselves, but one they find the most community in. My grandpa said: “If you live in Guyana, you would say you’re Guyanese, whether you’re black, white, Portuguese, Chinese or whatever. You’re still a Guyanese.”

While they are aware of the historical discontent between these groups, they nonetheless ascribe to them a single cultural-national identity that supersedes other ethnic affiliations—unlike “Canadian,” which they equate with whiteness. My grandpa even rejected the “Asian” label, and neither of them considered their non-Indian heritage, like my grandma’s Nepalese great-grandfather or my grandpa’s African grandmother.

Despite this perception of what it means to be Guyanese, he nonetheless sees himself reflected in India and the people living there, though he was less apt than my grandma to label himself as “Indian.” When I asked them whether they felt a connection to the country on their recent—and first—trip to India, he said that he “could have been one of these people […] they have your features, they have your complexion [… jokingly] the only thing you don’t have is their moustache.” These fickle and sometimes contradictory responses highlight the liminality that “double diasporics” can find themselves in. I thought that being first-generation might have made my grandparents more resolute in their answers than someone born in Canada like me, but I realize that these identifiers remain in constant flux, even for them.

On racism, or lack thereof

While my grandpa may not feel comfortable describing himself as “Canadian” as a result of being racialized, neither does he feel particularly victimized by white Canadians, either systemically or through individual interactions. He recalls one situation when, in a minor dispute with a gas station employee, he was told to “go back home.” Otherwise, my grandparents do not consider racism to be a problem for them. If anything, in their view, the only form of discrimination in Québec is “not related to your race, it’s just related to your language.” Earlier on, when my grandpa first arrived in England, he was pulled aside by an immigration officer who tested his bottle of Tylenol, suspecting that he was carrying illegal drugs. Interestingly, he does not seem to associate this interaction with racism, but rather frames it as just another hurdle in his migration experience.

In his study on the labour integration of Mexican migrants in Canada, Jesús Peña notes that these denials of racism are often based on a criterion of social power that includes age and class, as well as accent and language fluidity, among other factors (24). For their part, my grandparents were relatively young when they first migrated; they both experienced a degree of upward economic mobility, and their first language was English, albeit creolized. These factors, combined with the situation from which they departed in Guyana, could lend some insight into what, to me at least, was an unexpected perception of racism in Canada.

“Home”

Considering the many places my grandparents have lived over the decades, I asked where they might feel most at home. Although they expressed a level of affection for England, they both agreed on Canada. Neither wished to live in Guyana again. Given everything they shared with me that evening, I believe the strongest determining factor in what they consider to be their home is the presence of interpersonal connection. Neither of them has any close relatives living in Guyana anymore, and those that remain alive are largely in Canada. When I asked whether they missed Guyana, my grandpa said that he did until he met my grandma. Before then, he didn’t have any friends or family in London besides his brother. My grandma recalls crying over her mother when she first arrived in England, since she had migrated without her. For her, the most noteworthy attachment she had to Guyana was through a person.

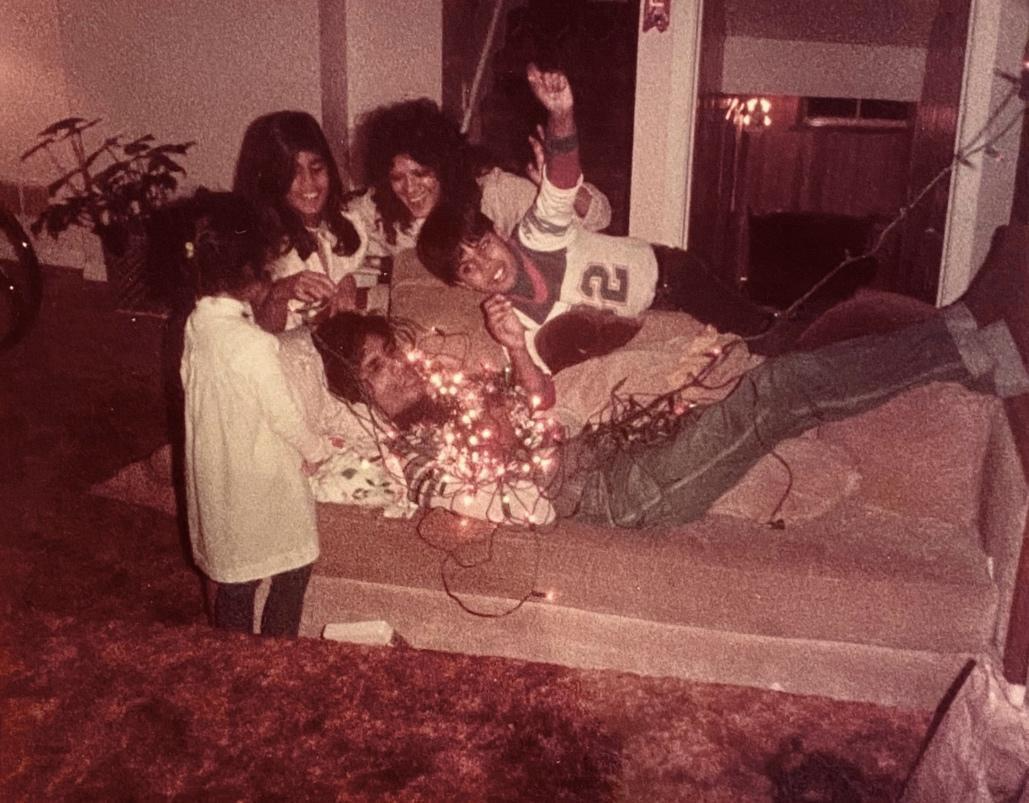

The significance of family in determining their home is exemplified by their repeated references to Christmas throughout the interview, recalling with fondness the dinners they would host in their London apartment during the holidays and the rare British Columbian apples they would get as children. Despite my grandma’s Muslim background, she celebrated Christmas as much as everyone around her did.

In her study on Caribbean migrants in Britain, Tracey Reynolds finds similar nostalgic associations with Christmas. She cites it as a medium through which the diaspora can exercise their connections to the Caribbean by celebrating customs that allow them to be part of globally dispersed kin networks (282). In the minds of many diasporic Caribbeans, Christmas is not an imported Western tradition associated with British colonialism or Christian evangelization, but is rather conceived of as a distinctly Caribbean tradition (286).

While I don’t celebrate it myself, some of my most tender memories were made during the Christmas gatherings my grandparents hosted every year. I remember the long, dark drives to their house and the long, warm evenings spent with the family I rarely saw. My childhood was coloured by the sweet dark syrup of Guyanese pepperpot, the meat of which became richer and softer with each passing day, though there was never much left over by the end of the night. I remember anticipating the masala chai my uncle sometimes made after dessert, watching him stir the large pot on the stove, mug in hand. The final goodbyes were prolonged in the foyer as I continued to play among cousins with only one foot in my shoe, no one yet ready for their inevitable departure.

My grandparents’ home has always been the junction between generations, the site of attachment-making to Guyana and beyond, localized within Québec. Though the family that originally brought them across the Atlantic and back again are no longer here, my grandparents still choose to stay for the new families that they have made and loved over a lifetime. And for as long as they are alive, we will continue to make a home for them here, too.

Works consulted

- Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Report of a Commission of Inquiry into Disturbances in British Guyana in February. 1962. https://www.parliament.gov.gy/documents/documents-laid/21040-report_on_disturbance_in_bg___feb._1962.pdf.

- Mars, Perry. “Ethnic Conflict and Political Control: The Guyana Case.” Social and Economic Studies 36, no. 3 (1990): 65-94. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27864954.

- Peña Muñoz, Jesús Javier. “‘There’s no Racism in Canada, but…’: The Canadian Experience and Labor Integration of the Mexican Creative Class in Toronto.” Migraciones Internacionales 8, no. 3 (2016): 10-36. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=15145348001.

- Premdas, Ralph R. “Guyana: Socialism and Destabilization in the Western Hemisphere.” Caribbean Quarterly 25, no. 3 (1979): 25-43. DOI: 10.1080/00086495.1979.11671954.

- Reynolds, Tracey. “Family and Community Networks in the (Re)making of Ethnic Identity of Caribbean Young People in Britain.” Community, Work and Family 9, no. 3 (2006): 273-290. DOI: 10.1080/13668800600743586.

- Saperstein, Aliya and Andrew M. Penner. “Beyond the Looking Glass: Exploring Fluidity in Racial Self-Identification and Interviewer Classification.” Sociological Perspectives 57, no. 2 (2014): 186-207. DOI: 10.1177/0731121414523732.

- Jabar, Saarah. Recorded interview with Errol Sears and Maylene Yamin, November 2024.

- Trotz, D. Alissa. “‘Lest We Forget’: Terror and the Politics of Commemoration in Guyana.” in At the Limits of Justice: Women of Colour on Terror, edited by Suvendrini Perera and Sherene Razack, 289-308. University of Toronto Press, 2014. DOI: 10.3138/9781442616455-019.