[Montreal April 6, 2015] Greece – Ελλάς or Hellas – is a place that for many people has existed only as a sunny spot visited from some monstrous cruise ship, or perhaps a mental image of a make-believe land with Leonard Cohen languishing by a beach.

There are also other, more real external perspectives, connected with realpolitik … those of imposing outside interests that have always looked on, or down, at Greece because of tangible needs all their own: The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), bankers, vulture funds.

Most outsiders, though, know little and care less about the history of the country, except for its most strikingly obvious features, such as the ancient Parthenon high up on the Acropolis over-looking downtown Athens.

April 1941: Germans raising flag on Acropolis. Credit: Bundesarchiv

But for Greeks, unlike visitors, their nation is a place fraught with history that each Greek carries within herself or himself. Everyone knows the various stages taken in the passage to modernity. The liberation from Ottoman rule. The incredibly tough fight against Italian Fascists and the Nazis during World War Two. The bitter civil strife of the 1940s. The dictatorship of the colonels from 1967 to 1974, that grim praetorian regime supported by the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States government.

At the present time, however, there is a change in this external indifference, because Greece is suddenly very much on the radar. Since 2008, its 11 million people have been thrust into a debt crisis of European, and even global dimensions that has made outsiders think about the really existing country and its everyday life.

After the global financial melt-down six years ago, Greece experienced a radical economic decline. In 2010, the then government entered into loan agreements with the much disliked “Troika” – the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund(IMF). Brussels bureaucrats and “inspectors” put Greece into an austerity program forcing the country to follow a “Memorandum” of agreement between external creditors and Athens. This quid pro quo is exactly like that applied in the past to countries in the Third World, except that Greece and its creditors are all part of the same currency union.

In exchange for bank credits, the Greek government was compelled to fire workers, curtail salaries and pensions, and privatize state-owned assets. Specialists warned the Greek Prime Minister of the time, George Papandreou, not to enter into this agreement, and one of those warning voices belonged to Yanis Varoufakis who is now the new Finance Minister in 2015.

Yanis Varoufakis. Credit: The Guardian

In the last four years, the country’s situation has only gotten worse. Greece’s accumulated debt is enormous – approximately $270 Billion Euros, with about $170 billion owed to European institutions and the International Monetary Fund. Some sources say the total debt burden is even higher. Accumulated debt obligations are estimated to be 175% of GDP.

Over the whole six-year period, from 2008 to 2014, Greece has lived through a depression, with GDP falling by a full 25%. Total unemployment is also 25%, sometimes more than that, and youth joblessness is about 50%. More than 115,000 highly trained professionals (roughly 1% of the total population) have been recorded as having left the country, and the emigration is continuing. Suicides have sky-rocketed, 30-year-olds are living with their parents, salaries have been cut drastically, mass lay-offs have hit the most vulnerable, and homelessness is rampant.

The medicine has been far worse than the disease and the imposed austerity has made a sustainable recovery impossible.

Yiannis Milios, a professor at the National Technical University, describes how this self-defeating logic works in these terms: “They [the Troika] keep dismantling the welfare state, they keep cutting wages and pensions and they say this is necessary to tackle the debt problem. However, the debt as a percentage of GDP constantly increases because the recessionary policies decrease the GDP which is the denominator of the whole index” (YouTube Interview with European Network on Debt and Development, with emphasis added by Montreal Serai).

Milios is a member of Syriza, the left coalition that won the January elections and has just formed an anti-austerity government under the leadership of the 40-year-old Prime Minister, Alexei Tsipras.

A new day seemed to have begun under the leadership of Tsipras with a government dedicated to undoing the past damage done to ordinary people, especially the young

When the Syriza government was elected on January 25th, it was striking to see the number of young people gathered in central Athens to welcome in the new, anti-austerity politicians. Finally, officials were going to try to do something for those who had filled in a multitude of job applications, getting one refusal after another, then often giving up altogether. These young call themselves “the lost generation” – and one of the penalties they pay is that they cannot grow up normally, since marginality often continues into a person’s thirties.

Alexei Tsipras is himself 40 years old, only a few years older than the veteran “lost ones.” And the Syriza government is full of very clever professional people who know first-hand the way the crisis has affected their particular group, among others.

One of these new faces in the government belongs to that economist, Yanis Varoufakis, the Finance Minister, the very man who warned against the austerity package four years ago.

He is now the point man conducting the painful debt negotiations. On February 20th, 2015 he secured a provisional 4-month loan extension agreement between the European Commission and Greece. In his Brussels press conference that afternoon Varoufakis spoke of “enormous pressure,” part of which was the torrent of Euro-denominated deposits leaving Greek banks at the very time the loan talks were going on.

Millions of people – during the week of talks in Brussels – watched this Greek Finance Minister wearing an open-necked shirt and a leather jacket, as he vigorously spoke for the Greek people, and especially the young.

Varoufakis tells a poignant story of a government-appointed translator who accompanied him when an official Spanish visitor came to Athens. Taking the Minister aside, the translator confided that he had been living in the streets for two years, a fact that he did not dare tell his son. “I am finished,” this educated man told Varoufakis, “please – do something for my son and his future.”

The February 20th agreement is now more than six weeks old. Basically, that text promises a crackdown on tax evasion in Greece, a serious attack on corruption in the state bureaucracy, and a certain reciprocal accommodation between the parties. For its part, Athens is attempting not to compromise the domestic promises on which the government was elected.

That electoral promise has a name – the Thessaloniki program –and it rests on four commitments:

1. Confronting the humanitarian crisis.

2. Restarting the economy and promoting tax justice

3. Creating a national plan

4. Deepening democracy

Up to this time, however, Greeks have experienced their situation as a kind of “economic occupation” by the major economic powers in Europe, principally the Germans.

During this past winter, as the dour German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble went head-to-head with Varoufakis in their talks, a great number of old memories came to the surface regarding the Germans and their history in the Balkans.

Exhibit of the Greek Foreign Ministry

And in the Greek historical memory, one of the dramatic highlights has been the memory of a symbolic act of resistance during the Nazi occupation of Athens. On the night of May 30, 1941, two young students – Apostolos Santas and Manolis Glezos – climbed the Acropolis at night and tore down the swastika banner that had been placed there by occupying German soldiers.

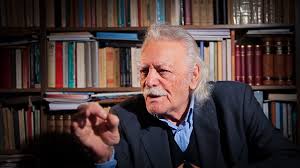

Glezos. Credit: The Bell

Manolis Glezos is still alive at 93 and has had a full, distinguished life as a journalist and political figure. He is also a Syriza member of the European Parliament, but shortly after the Feb. 20th agreement he vigorously indicated his opposition to it – saying that he wanted to apologize to the Greek people for participating in “this illusion.”

Here is what Glezos has written on the website of the Active Citizens’ Movement in Greece:

The Greek people voted for what Syriza promised: that we abolish the regime of austerity, which is the strategy not only of the oligarchies of Germany and the other creditor countries but also of the Greek oligarchy; that we abrogate the Memorandum and the Troika and all the austerity legislation; that the next day, with one law, we abolish the Troika and its consequences.

A month has passed and this promise has yet to become action.

It is a pity indeed.

From my part, I apologize to the Greek people for having assisted in this illusion.

(trans. Panogiotis Sotiris, courtesy Huffington Post)

Glezos represents the opposition inside Syriza to the ongoing negotiations, and those opponents of the negotiation as it now stands represent about four out of ten of the party’s leadership.

There is no question that the Tsipras government has risked destroying its own support. Essentially, Varoufakis has gained a very limited breathing period for the Athens authorities to begin repairing the damage done by austerity. Tsipras and the Syriza leadership are also very conscious of the danger posed by the fascist political party in Greece, Golden Dawn. The elaborate tactical dance between Varoufakis and the EU officials will continue all this spring and there is still a very great possibility that the process will break down.

The economic situation is not good. In the last quarter of 2014, the Greek economy dipped – again – and surveys indicate that this winter and spring his same trend will continue. The deflation of prices is worsening, so clearly the recessionary policies promoted by Brussels are still exacting a terrible cost that makes it impossible for the economy to rebound – and all the time there is a constant need for outside funds to fuel the process.

As of the date of this article — April 6, 2015 — a whole new round of tension is looming between Athens and the “Troika.” On April 9th the Greek government has 450 million Euros due for payment to the International Monetary Fund, and on April 14th it has to meet payments for salaries and pensions within the country. Reportedly there is not enough money on hand for both obligations to be met. One of the best informed European journalists about the situation is Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of The Telegraph in Britain. On April 2nd he co–authored a story that began: “Greece is drawing up drastic plans to nationalise the country’s banking system and introduce a parallel currency unless the eurozone takes steps to defuse the simmering crisis and soften its demands” (“Greece draws up drachma plans, prepares to miss IMF payment,” The Telegraph April 2, 2015). Now it has just been announced, after a two-hour Easter Sunday meeting between Yanis Varoufakis and Christine Lagarde of the IMF, that Greece will meet the April 9th IMF payment. The dance of tactics, bluff, and confusion, goes on…

Within Greece, the press that is critical of the Tsipras team is also sounding the alarm. The well-known daily To Vima — The Tribune in English– wrote on March 27th: “At present the government is scraping the bottom of the barrel. It is seizing the remaining resources of public organizations, insurance funds, even local government, in order to delay a visible default.” Speculation has it that Athens may very well purposely become the first government of a developed, European country to default on an IMF loan, precisely to make the Troika take the situation more seriously.

This ongoing drama began in February with the last-moment agreement that was reached then. As the world watched at that time, there was no question that Greece had stood up and made its voice heard during those debt negotiations.

On Feb. 20th 2015 — the day the first provisional debt agreement was announced in Brussels — Serai was in Montreal and sharing the company of a member of Syriza New York, Prof. Natassa Romanou, while she visited in the home of Dimitrios Roussopoulos, the publisher of Montreal’s Black Rose Books.

Syriza New York is a group formed in New York City to support the efforts of Syriza to work its way out of the austerity labyrinth.

Natassa Romanou. Credit: P. Barnard

Natassa Romanou, like a lot of Syriza members, is highly distinguished in her field. She is a Professor in Columbia University’s Dept. of Applied Physics and Applied Mathematics, and she works at The Godard Institute for Space Studies, part of the Columbia University Earth Institute that is working on climate models. Her specialty is climate change and the ocean.

On the day of those negotiations, Natassa Romanou felt that Greece had won some room to pursue needed policies at home, and Serai was privileged to ask her about her immediate reactions.

Here is the interview between Serai and Natassa Romanou just as the Feb. 20th loan extension agreement was finalized. We publish these remarks now, in April 2015, because we feel that they give our readers a glimpse into the thinking, and the aspirations, of people in Greece today.

Serai: What is your impression of what has been agreed today, Feb. 20th, 2015?

Natassa Romanou: We don’t have the full details of the agreement yet. We don’t know whether it is an agreement or some parts of it still need to be decided. It seems that it’s a very positive view that both sides have given up some ground and have come to a common decision. For me, the best clause that I have heard is that the government doesn’t need to take any more measures that are combined to the bailout package. I think that unties the hands of the government to implement its Thessaloniki Programme which they were elected for by the Greek people, which the Greek people desperately need to start getting out of the crisis and I think it’s very positive.

Serai: Is it your understanding that this agreement today will not compromise the basic programme of the government now in Greece?

Natassa Romanou: We have to see what has been decided upon, but the fact that we are not going to take any more measures along the lines that the Troika had announced earlier – more lay-offs, more taxation [for the poorer sections of the population] – this is very positive. There were no other requirements for the government other than what the government has already committed to – for example, resolving the taxation issue in Greece [the issue of tax evasion by the wealthy], becoming more fair and equitable, cutting down corruption, attacking corruption, and so forth. I think that these are measures the government itself wants to do, they are not imposed by the Troika and they will start giving relief to the population.

Serai: I heard you speak to young people in Montreal and you said that you hope that Southern Europe – Greece, Italy perhaps, certainly people in Spain – will be forging a new vision, a new idea of Europe. Is that your feeling and is that the feeling of the government in Athens today?

Natassa Romanou: Certainly, the feeling of the people – and that is what is important – of the people in Southern Europe, and my personal feeling as well, is that the way the European Union operates right now, its institutional laws and some of the impositions of measures to the people and directives that it gives out to the peoples of Europe are not equitable and they do not align with the spirit of the European Union, with the reasons it was formed, and so they have to be revised. And as the popular movements across Europe are taking power, that is now within sight.

Serai: And do you think that new view of Europe is truly there in the South and will perhaps move northwards?

Natassa Romanou: It is definitely in the view of the people in Spain and in Greece and in Italy because they have been suffering under the austerity measures. And so they understand that austerity has been imposed from the bureaucrats and the technocrats in the European Union. And I think that realization will also emancipate the people in Central and Northern Europe who may not yet have experienced austerity to the degree that the Southern Europeans have, but they are definitely the victims down the road.

Serai: What is so striking about the new government in Athens is that this is a government that has stood up against this very grey, ugly, and ultimately self-defeating consensus. So this is extremely impressive to a lot of people around the world, I would say.

Natassa Romanou: I agree with you. This is what has mobilized people across the Atlantic Ocean in North America and South America as well to watch very closely the developments in Europe because they can see the correlation, they can see the analogies with their own state of affairs in their own countries with austerity being imposed now worldwide, and the fight they have to put up and eventually win.

Serai: Could you give us a short sketch of what you have said in your public presentation here in Montreal?

Natassa Romanou: I think the main points that I tried to make were to outline what the austerity measures were in Greece and why they were taken up by the previous Greek government, why they were imposed by the European Union. Syriza was saying before the election that the debt crisis was a pretext to impose austerity upon the European countries, to restrict labour laws, to cut down public spending. It was an excuse to build up all these revenues and put them back in private hands rather than back into the state. That has caused a humanitarian crisis in Greece and threatens to cause a humanitarian crisis in other countries as well. People have lost jobs, their houses, they can’t pay their electricity, people are now below the poverty line…suicides and homelessness…these are facts which everyday people can see all around them and what was missing up until Syriza came into the political arena was the actual connection between the cause and the effect. The cause being the fact that the European Union wanted to implement these measures – and the effect was implementing these measures and people suffering.

Serai: Martin Wolf of The Financial Times has written frequently in the last few years about Germany’s problem. Germany’s problem is that it has a huge surplus. If you have this huge surplus, and you have a huge amount of capital, someone else doesn’t have capital, and someone else has a deficit. Do you think the Germans are beginning to realize that they have a problem?

Natassa Romanou: It’s very hard to change your game when you are on top of it, of course, but the truth of the matter is that the surpluses that Germany has accumulated over the years of the crisis are essentially the debts that the peripheral countries are paying to Germany and this is very important if we want to move towards the direction of a unified Europe to understand that these kinds of distinctions – two-tier economies being developed on the continent –they have to be stopped. And this is why Syriza, Podemos [the Spanish opposition movement] and the other forces in Southern Europe are saying that we need to change Europe itself if we want to have a unified Europe. We have to change the institutions to take into account these kinds of contradictions and try to eliminate them.

Serai: Thomas Piketty’s book Capital in the Twenty-First Century points to the fact that we are in danger of returning to the Belle Époque [the period of intense capital accumulation prior to World War One]. In the Belle Époque there were surpluses and the export of capital from France and Britain to the colonies. So, this kind of massive surplus and massive accumulation of capital in the one country or one or two countries basically creates a colonial relationship between the center and the periphery. Do you think that insight needs to be brought forward in Europe?

Natassa Romanou: This is the insight that needs to be explained when we are describing the terms of the Greek crisis or the debt crisis in Europe right now. It is precisely the fact that Southern Europe has been essentially colonized, is a protectorate now of Central Europe, of the technocrats of the European Union who are not only accumulating the wealth, taking out the wealth from the periphery, but at the same time imposing measures and directives of how the countries should be run which obviously takes sovereignty away from the countries themselves.

Serai: Syriza is committed to Europe at the same time that it has been critical. Does this mean that in the months and years to come Syriza will be speaking to other Europeans about changing this relation between North and South, between the center and the periphery?

Natassa Romanou: Syriza has fought very hard to stay with the European Union and we’ve seen this since the election [of Syriza in January 2015]. However, what Syriza has committed to is also to change the European Union. The European Union has not served its citizens during these years of crisis. It has not moved towards more integration. It has moved towards a two-tier union, two-tiered citizens in the union, those who do have and those who have not, and that needs to be changed. This is understood by people in other peripheral countries in the union, and Syriza will be aligning its forces with these forces, with these forces in the other countries to help change Europe.

Serai: How will Syriza deal with the practical economic problems in the months to come?

Natassa Romanou: The first priority will be addressing the humanitarian crisis because this is the most pressing issue right now in Greece. Secondly, it will have to empower employment, raise the minimum wage, and put back protective laws for working people. For all this to happen, Syriza will have to find the funds for it and the way that it has pledged to do so is by taxing those who were not taxed before, addressing tax evasion and tax immunity, and these will be the first-year aims for the new government.

Serai: So – the word for today is kala? [good]

Natassa Romanou: …Yes

Serai: Efharisto [thank you].

Pimento Report #89: Syriza

Examination of the Greek Debt Crisis and the Feb. 20th 2015 Agreement…with Natassa Romanou of Syriza New York