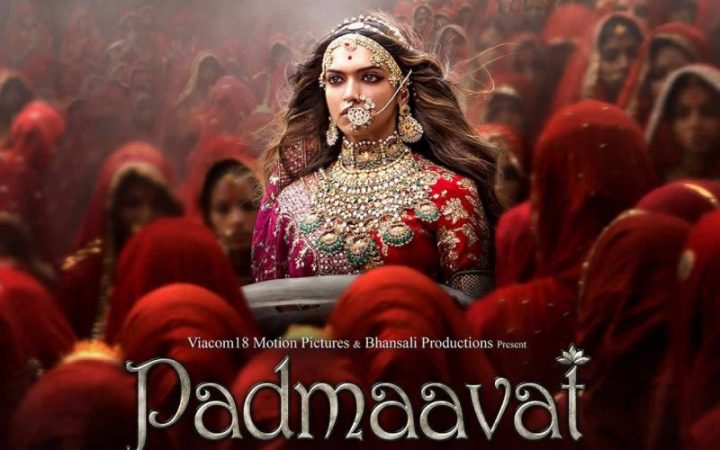

Padmaavat (2018), Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s latest magnum opus, became mostly notorious for what was claimed as its attack on Rajput pride and its portrayal of the legendary queen Padmavati (the story of the film was based on a poem written on Queen Padmavati’s life by a fifteenth-century poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi). Before anyone had even watched the film, there were rumours that Queen Padmavati was depicted in a romantic/intimate scene with Allauddin Khilji. The very idea of Padmavati and Khilji together was abhorrent to pure-blooded Rajputs, as it was an attack on the honour of the Queen, revered as an icon and queen mother in many parts of India’s northern province of Rajasthan. The rumours were unfounded and after a four-month period of protests and rioting in the streets, the courts intervened, and in February 2018, the film finally made it to screens both in India and around the world. It didn’t take more than a few screenings for the truth to spill out that the film was more designed to celebrate Rajput pride, a valorization that played directly into the idea of Hindu pride. At the last count the film had raked in close to 6 billion Indian Rupees at the box-office (just shy of $100 million).

I sat watching the film, and quite unexpectedly my mind went racing back to other films made by Bhansali in the last two decades. This meandering took me even further to other filmmakers I had enjoyed and grown up watching in a small town in Northern India: Raj Kapoor, Sooraj Barjatya, Rajkumar Santoshi, Ashutosh Gowariker, all names of renowned Bollywood filmmakers. It dawned on me that although the similarity between the films they made, the stories they told, and the ideas they perpetuated was telling, I had been oblivious to it.

For all its ills, Bollywood has held sway in the past hundred years and continues to dominate and dictate the cultural discourse that goes on in the Indian Sub-continent and beyond. It has also become this dominant cultural export out of South Asia. While alternative voices exist and thrive, there is little debate that the loudest voice is still that of Bollywood. But how does the dominance of this industry determine the cultural debate in India and play into the nationalist, majoritarian narrative that has recently swept the Sub-continent? In reflecting on my learnings about cinema and the understanding of my social and cultural identity, I began probing into what contributed to this framing. This makes these reflections more of an imperative, given the political and social climate that currently exists in India.

As a young person, I consumed cinema in all its poetry, including the grandeur that Bhansali portrayed in his films. When stories seem to speak to some aspect of what is around you, you assume that that is all there is. The engagement starts with childish awe, fed by ideas of stardom, music and glamour. For a young person, this is also aspirational. You want to be one with the stars. You want to sing and dance like them, you want to be part of their families. And I think it’s quite natural to grow up in a middle-class environment, not attempting to engage with more than what meets the eye. I’d say that with the ever-expanding social media and its penetration throughout the nooks and crannies of small towns and villages, things may have begun to shift across India. However the aspirational quality of cinema has remained intact.

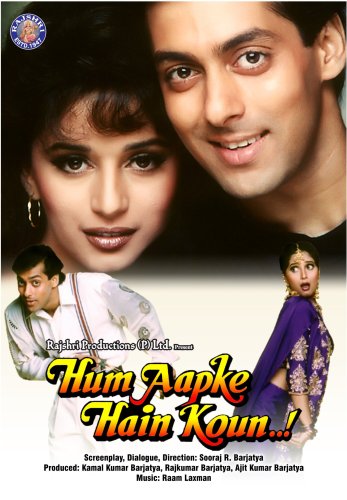

But what is it that we are aspiring for? What starts out as a starry-eyed view of the world becomes problematic, particularly owing to the consistent homogeneity of representations and narratives. So, the idea of a middle-class family, as seen through what surrounds you, on screen and off it, is the stereotypical heteronormative Hindu reality. This statement of fact is no generalization. While the family drama romance has matured from say a Hum Aapke Hain Kaun (1994) to a Badrinath Ki Dulhaniya (2017), the underlying ethos and identities have stayed firm and mostly static.

Padmaavat was no outlier in this, rather exemplified what’s been done for decades. I remember that in 1982 a Hindi film named Nikaah was hailed as a landmark ‘Muslim Social’ that saw an upper middle-class Muslim family depicted in a mainstream Bollywood film. The film wasn’t a first, as pre-1980s had seen sporadic depiction of Muslim characters and stories, but Nikaah mainstreamed even the social problem of Triple-Talaq (irrevocable divorce), and thus received more traction.

Tokenism is used to ‘include’ characters from minority communities and to try to weave diverse representations in the narratives that are fed to us. However, there is continuous and sub-textual engagement with the Hindu hegemony when Indian culture and access to it is depicted and learned through the lens of cinema. It’s rather hilarious that even the wedding scene in English Vinglish (2012) stayed true to its Hindu South Asian roots, notwithstanding its location (United States) and its time. My critique isn’t to suggest that Indian culture (whatever that unitary idea even means) shouldn’t be represented through song and dance and Diwali celebrations and weddings. Culture is an inalienable part of the identity of any populace. My question is how much of what we see depicted in the movies that we watch and consume out of Bollywood is a product of a real evaluation and/or analysis of what Indian culture really is? It is telling that a lot of socially relevant cinema movements around South Asia, led by brilliant filmmakers like Satyajit Ray, Shyam Benegal, Mrinal Sen, etc., remained on the fringes. So while there was evaluation and re-evaluation being done, it was continually on the margins.

The head of the Rashtra Swayamsewak Sangh (commonly referred to by the acronym RSS), Shri Mohan Bhagwat, in defining India’s cultural identity in 2014 clearly stated that Hindutva is the cultural identity of all Indians. He went as far to say that one can be a Muslim, Christian, Sikh, but the cultural identity of the land called India remains rooted in Hinduism. As the political ideologue of the current government in office, this idea of the RSS is neither a coincidence, nor is it a minority voice. There is a concerted effort to change by forced assertion the diverse nature of a historical, cultural and geographic entity that is the modern nation state India.

While Padmaavat may not be an outlier, things have seen a bit of change. South Asia is not just religiously diverse, it is also economically diverse, and a new breed of filmmaking is now focussing on stories from small towns and communities. Filmmakers like Vishal Bharadwaj (Haider 2014), Anubhav Sinha (Mulk 2018), Zoya Akhtar (Lust Stories 2018), Anurag Kashyap, and Imtiaz Ali have been demonstrating encouraging signs of a change in the narrative. What is important though is that in their attempts to change the narrative, they now seem to focus on the urban-rural divide, and we are still grappling with the perpetuated notions of the image of India: is it social, cultural, or spiritual? I am yet to see that my protagonist is anyone but a middle-class heteronormative Hindu male (with some marginal room for females), who is fighting against the system, looking to win over a love interest, or overcoming personal odds to move ahead in the world.

The maturity of cultural representation is evident when a people can laugh at themselves and when a culture can tell stories as varied as the breakup of a marriage due to the lack of a village toilet (Toilet ek Prem Katha 2017), erectile dysfunction (Shubh Mangal Savdhaan 2017), and women’s empowerment being spearheaded by a witch (Stree 2018). Having arrived at this level of maturity, it is critical now to debate and dispel the idea of a homogenous, majoritarian social and cultural identity.

I wish I could subscribe to the view that something like Padmaavat is merely meant to entertain or recreate a historical (some question its veracity) piece for a contemporary audience, with no impact whatsoever on how we self-identify. These larger-than-life narratives speak to the heart of an audience’s psyche, which then manifests itself into reaffirming sectarian ideas of nationhood and identity that further fuel intolerance of what we deem the ‘other.’ This othering is empowered by the fact that social discourse and popular culture perpetuate the idea of a homogenous majoritarian whole, which demands assimilation.

I am certainly not expecting a miracle by which the majoritarian view of culture and a nation, including its social identity, will give up reins of power and control over the discourse. I am hoping that incrementally at least, we will see Indian cinema (particularly the all-powerful Bollywood) truly become a mirror to, and of, the people it very successfully entertains.