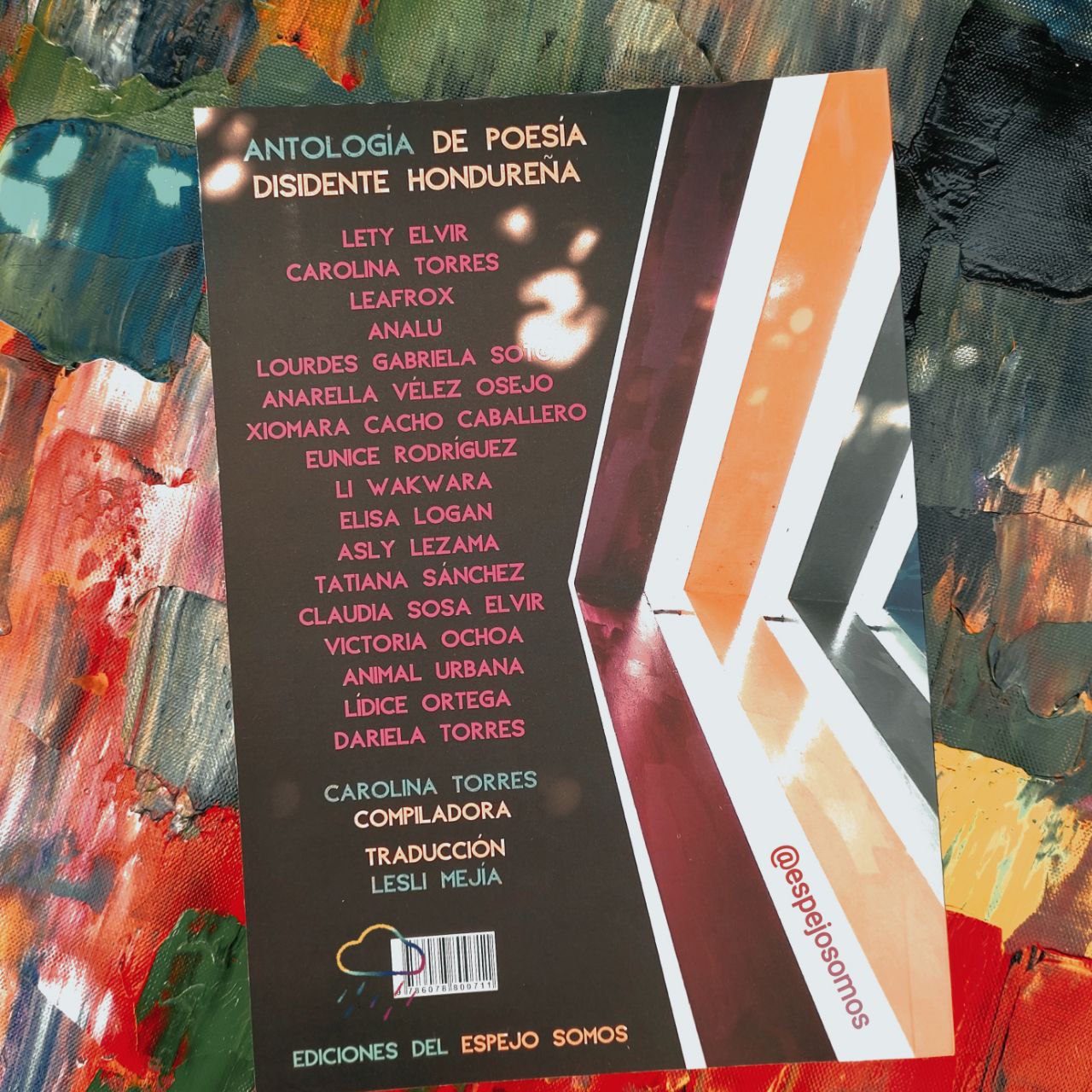

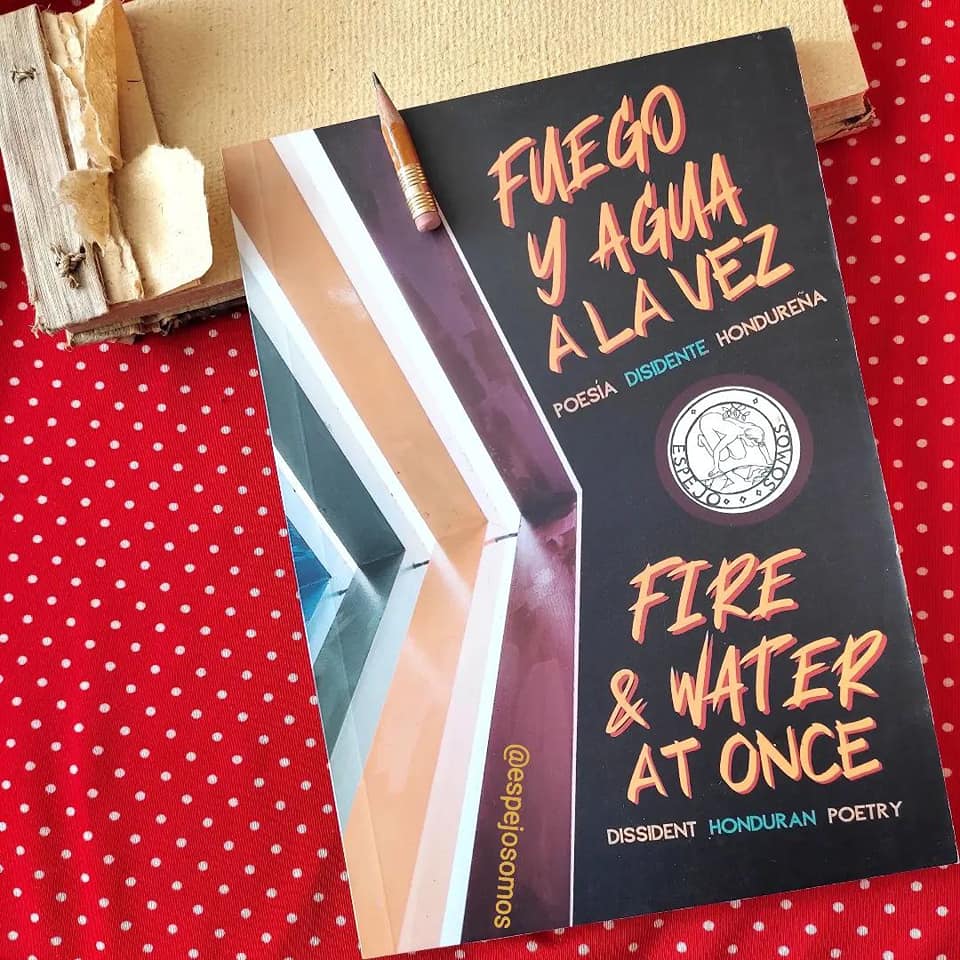

Fire & Water at Once: Dissident Honduran Poetry

Compiled by Carolina Torres, translated by Lesli Mejía, Ediciones del espejo somos (Chiapas), 2022, 140 pages

Fuego y agua a la vez / Fire and Water at Once is a Spanish-English bilingual anthology of poetry penned by 17 Honduran poets and published by Espejo Somos. It is no coincidence that this compilation of very candid and sometimes fiery writings by self-styled dissident poets was published in Mexico in San Cristobal de las Casas, a magical town celebrated for its rich and ancient Indigenous culture. The fact that the authors were reticent or perhaps simply unable to publish their work in Honduras speaks to the repression and violence that many marginalized people have historically suffered in Honduras and elsewhere.

But first a word about the layout of the poems in this book. Each author’s work is initially presented in Spanish then in English, without any attempt to juxtapose the two. This sequencing might create a bit of confusion for absent-minded bilingual readers who blithely go on to read the same poem in another language without realizing it is a translation. (Any such confusion, of course, is a testament to the skill of the translator, Lesli Mejía.)

Carolina Torres has done an excellent job of compiling a far-reaching selection of poetry, followed by Denise Cazes’ careful editorial work. Lesli Mejía has been more than up to the task of translating poems in which gender-inclusive grammar in Spanish follows a very different logic from that of the English. As a reviewer and as a native Spanish-speaker, I am often confounded by gender-inclusive pronouns that, in my mind, can interfere with the musicality of the poem, particularly when an “x” is meant to replace a vowel… but my reaction may well be attributable to my generation and to my limited contact with Hispanic literature in Canada.

Since Montréal Serai is mainly an anglophone publication, I will limit my remarks to the English version of the poems, but I urge readers to get a copy and read the originals as well.

Lety Elvir, in introducing her poetry, decries the ignorance and negligence of bureaucrats in regard to culture, but expresses the hope that with a woman president now leading the country (Xiomara Castro, inaugurated on January 27, 2022), things will change.

In “One in the Morning/Two Cities,” she laments: “There, in our city / — the most violent on Earth / where everyone fears going / because war abounds — / it is one in the morning / you sleep / and I remember you.”

Carolina Torres is more optimistic because “there are now more collectives, more voices that break the establishment, which I believe is beautiful.”

Torres proposes “a strike against silence, / against established masks, / against suffocating parameters.”

Lea Frox’s self-description reads as follows: “A Black Afro-indigenous non-binary person, as well as an antiracist lesbian artist, poet, writer, and a member of the De pueblo y barrio collective.”

The author’s take on police brutality is clear: “We feel the fear on our steps / backs / sides / the patrol cars activate their misnamed sirens / they walk slowly by our tired / impoverished/ black/ indigenous / racialized bodies…”

Analu decries the fact that “The situation of literature in Honduras is chauvinistic because most of the popular productions are hegemonic and patriarchal…” In “A November Sunday,” the poet tells readers: “I feel on the edge / I feel suffocated/ I feel fake / I feel.”

Lourdes Gabriela Soto laments the lack of government support for writers but expresses optimism with the explosion of social media.

The author discovers that “God does not exist / and if he does / he is not the same they told me about.”

Anarella Vélez Osejo has a rich and varied academic and publications background. Still, “Life can be like dizziness / Life can be like nausea / Life can be an escape / Life can be like a suicide…”

Xiomara Cacho Caballero’s “works center on the loss of identity, the fragmentation of consciousness, and the struggle to persevere my ethnic group’s memory despite the adversities.”

The author laments that “There is nowhere to hide / the sun burns mercilessly / and we all seek refuge and relief…”

Eunice Rodríguez comes from a theatre and journalism background. In the prose piece entitled “The Monster that Pretends to Be Good,” the writer gives a harrowing account of a 10-year-old girl raped in the street by a benevolent-looking figure.

In “Distanced,” the author wails: “I don’t know who I am anymore! / Physically I look like a woman / but inside / I am more of a man than Bush / Could I be crazy? / Why do you judge me? / Can’t you see! That I wish to be free…?”

Li Wakwara’s self-description is that of an “indigenous, bi/pansexual/non binary trans person, as well as an antiracist and anti-patriarchal sexual dissident, writer, poet, popular educator, artisan and member of the De Pueblo y Barrio collective. In a prose piece entitled “The Peoples Are Diversity,” the writer refers to the intersections between capitalism, patriarchy, colonization and much more.

“In Feelings, Pleasures, and Eroticisms,” the poet makes a call: “Let us build anal collusions / And may racism and colonialism stop fucking our existence / Come with me and let us come all our lives.”

Elisa Logan, also known as Elizabeth Garcia, is a social worker and professor of literature, Spanish and French. “Fruit Women” is a poem dedicated to Berta Cáceres and Bety Cariño, the former a Honduran Indigenous environmental activist and the latter a Mexican Indigenous human rights activist. Cáceres was assassinated in 2016, and Cariño was killed in 2010. In Logan’s words: “They planted their words / in the chest / in the soul / in the love for the earth / for its entrails and its fruits / in the furious desire for justice…”

Asly Lezama believes “that writing is a way of screaming what I feel, of becoming present, past, and future, and of creating new possibilities.” The poet makes a case for engaged sex: “I do not fuck and turn around / While fucking I want to see you / feel you / and afterwards / talk…”

Tatiana Sánchez is a linguist and university professor in Honduras. Sánchez believes that marriage is a cage. “I have made the decision! Yes! Today I am getting out of here, of this stupid legal cage.”

Claudia Sosa Elvir is a writer and physician who writes about men and disappeared women. “None of them imagined that his expensive suits were stained with innocent blood.”

Victoria Ochoa firmly believes that “Poetry is the act of extracting beauty out of the ordinary.”

In the poet’s words, “The river now surrenders the ocean and the waves are what dances between my eardrums. The waves, Virginia, become ink, and through words they express two letters. One is for you and the other is for me.”

Animal Urbana/Luciérnaga Poética’s self-definition is that of a “Neurodivergent, bisexual, non-binary person. I consider myself a creator, poet, and writer.”

The author further elaborates in a poem: “Essentially / I self-am a long list / of words / that come and go / that scream and vanish / entirely / forever…”

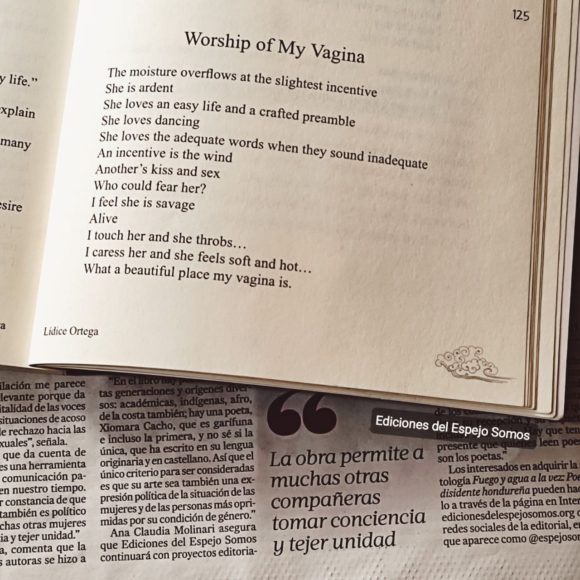

Lídice Ortega is a “Honduran, feminist, and communitarian political scientist who is passionate about the processes of collective and participative construction.” The author is a proponent of “Self-love / I love you / I love you / Your tits which have nourished / Your vagina which has caused pleasures / Has given life to inanimate beings…”

Dariela Torres is an anti-racist and anti-patriarchal activist, poet and editor, and cofounder of the literary magazine Ek Chapat.

“Out of rage hope is born / I speak from the fire wounds / I speak from the other side of the bloodied bread / I am a terrorist / I write Molotov verses / I set fire to my voices…”

This compilation of poems and short prose pieces by marginalized Honduran writers reflects the diversity of intent and life experience of the authors themselves. It is indeed a book full of Fire and Water at Once.

Fuego y agua a la vez / Fire and Water at Once is available through Ediciones del Espejo somos