Three years ago, I graduated with a degree in political science. By then, however, I had developed an apolitical temperament to go with it. As much as I enjoyed studying the workings of the world, I was repulsed by politics and its divisive nature. After completing my bachelor’s degree, I tuned out as much as possible from political debates and commentary. I found that many people who talk about politics often repeat ideas without verifying them, further spreading misinformation. I despised the way politics caused rifts and tensions, sometimes even animosity, in social situations.

Selfishly, I hid in my Western bubble, detached from the atrocious realities faced by others. I had the privilege of doing so. Unlike many people, I could go on with my day without worrying about war, famine or safety. My scope of distress was limited to getting through my dead-end job, hoping the bus wouldn’t be too crowded and mustering the willpower to make my own lunch in the morning.

I convinced myself that political debates were pointless. Since it didn’t seem like we could change anything anyway, I could only see how they ruined social gatherings. I wanted peace—even if it meant avoidance. Many people share this sentiment. They sympathize with what they see on the news but feel comforted by their own perceived powerlessness.

My fragile sense of peace was collapsing.

When the Palestinian-Israeli conflict escalated over 15 months ago, it became harder for me to maintain my mask of avoidance. My fragile sense of peace was collapsing. Reality was hitting me in the face through Instagram reels, family dinner-table conversations and on the streets on my way to work. Everyone wanted to talk about it. I realized that the only way out was through. Maybe, if we talked about it enough, people would eventually move on, and I could return to my bubble.

I forced myself to engage with people, even if I disagreed with them—especially then.

I forced myself to engage with people, even if I disagreed with them—especially then. I stopped myself from rebutting arguments and instead held back to listen and understand what the other person was saying. In this process, I learned that real peace is not about sweeping things under the rug. Eventually, the dust piles up, and you can no longer ignore it.

True peace can only begin to blossom through tough conversations—communicating with people holding a divergent viewpoint and aiming to find some middle ground. I am aware that things are far too complex to be solved just by talking about them, and it will take much more than playing devil’s advocate to bridge the gap between opposing parties. I certainly don’t mean to reduce serious war crimes, for instance, to mere miscommunication. However, I do think that communication on a micro level could pave the way for broader changes.

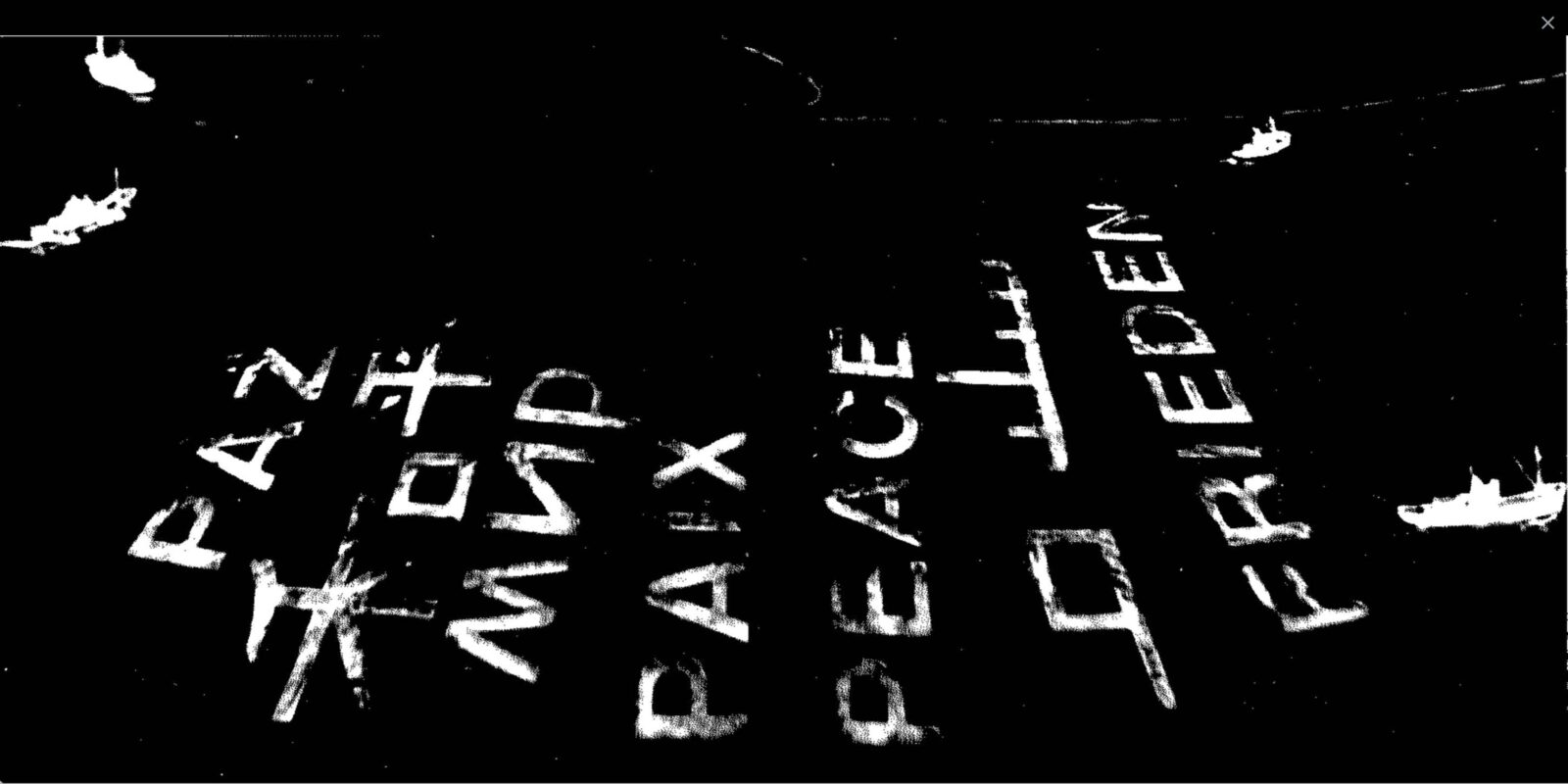

Our calls for peace often manifest as catchy slogans and Instagram hashtags. We’ve become accustomed to appealing to people’s emotions because it’s much easier than appealing to their intellect. It’s far easier to gain attention through sensationalizing a cause than by actively trying to understand its complexity. I don’t deny the good intentions of those who participate in flashy demonstrations, but I’ve noticed that this sort of crowd behaviour does little to bring about true peace.

In an article entitled “My Hope for Palestine” for The Atlantic (December 2024), Palestinian author Samer Sinijlawi explains that the extreme sentiments portrayed in demonstrations can be an obstacle to peace for Palestinians. While Sinijlawi does not condemn peaceful protesting, he points out that aggressive demonstrations or slogans that only rile up emotions do little to promote peace. Instead, they entrench the positions of both sides, making reconciliation, negotiation and compromise more difficult. As both sides continue to protest each other, there is no room for dialogue and the potential for peace becomes ever more elusive.

The road to cooperation cannot be shortcut by headlines and clickbait articles. Getting there requires sitting through uncomfortable conversations, digging to find the truth, doing the research and, hopefully, crossing to the other side with a better understanding of each other.

When I push myself to speak to people who are polar opposites to me—whether about the Palestinian-Israeli conflict or any other moral or political issue—I find that perspectives become more nuanced, more insightful. Even when I disagree with them, it paves the way for consensus. Negotiation becomes much easier when you understand why the opposing party thinks the way they do.

Coming from a Muslim and Iraqi community, I find that some of my people tend to alienate themselves from those who don’t share the same values. They stick to tight-knit groups that echo their beliefs and often reduce any non-Muslim to an “ajnabi” (foreigner). Likewise, living in Canada, I have experienced being othered by some of my fellow Westerners. They often prefer to assume things about me or my faith rather than risk the vulnerability of asking.

There’s no room for diplomacy or harmony to grow if all parties refuse to have the tough conversations.

I’ve been reduced to stereotypes numerous times without ever being given the chance to prove they don’t apply. Whether the alienating behaviour comes from the former or the latter, the common denominator is an unwillingness to communicate, to engage in healthy dialogue and to risk being wrong. Unfortunately, this only exacerbates the ideological divide. There’s no room for diplomacy or harmony to grow if all parties refuse to have the tough conversations. I welcome all questions about my faith or culture, no matter how redundant they may seem, because I’ve learned that it is always better to ask a “stupid” question than to assume a wrong answer.

Sinijlawi recounts that while he was imprisoned, he realized for the first time that the Israelis were just as afraid as he was. They had their own fears, and the sentiments expressed by the mass media didn’t reflect that. As hard as it was to accept that they too were afraid of the violence inflicted upon them, this experience helped him better understand the other side.

In prison, Sinijlawi saw his opponents for who they were, learned their names and spoke their language. He learned how to negotiate with them and bargain for the best possible outcome for his people. His story shows that the only way out is through. Peace cannot be achieved through pressure tactics, moralizing or chanting for freedom and dignity. Any other person in Sinijlawi’s position could have easily walked out of imprisonment with a tank full of hostility and resentment. Instead, he chose differently.

Likewise, in everyday life, we can choose differently as well. I strive to befriend people who don’t share my values or opinions. Through these relationships—many of which have turned into lasting friendships—we’ve been able to mutually nuance each other’s perspectives, despite our disagreements.

Sinijlawi posits that if he were the president of Palestine, he would want the Israeli president to be his best friend—not for his own sake, but for the sake of the Palestinians, to pave the way for negotiation and compromise to establish true peace. Whether it’s the case of Palestine vs. Israel, Muslim vs. Jew, Westerner vs. Easterner, or you vs. anyone who stands at the other end of your moral spectrum, the way to work in synergy in such a cosmopolitan world where clashes are inevitable is to step beyond the bubble and open the door for communication with the “other.” Only then can the promise of peace truly materialize.